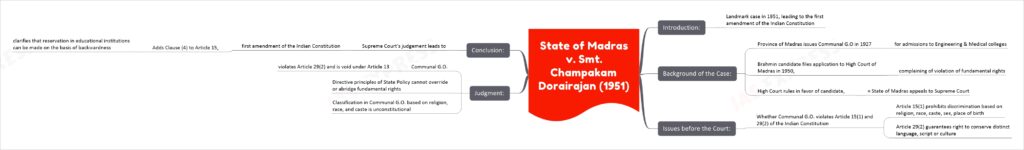

State of Madras v. Smt. Champakam Dorairajan (1951) – Reservation in Educational Institutions case

Introduction:

- The case of Smt. Champakam Dorairajan v/s state of Madras is a landmark case that was delivered by the Supreme Court of India in 1951.

- This case along with the case of Romesh Thappar v/s state of Madras, led to the first amendment of the Indian Constitution.

Background of the Case:

- In 1927, Province of Madras had issued a government order known as Communal G.O, with regard to the admission of students to the Engineering & Medical collages of the state.

- The order stated that the seats in Engineering & Medical Collages should be filled on the following basis: 6 seats for Non-Brahmin Hindus, 2 seats for Backward Hindus, 2 seats for Brahmins, 2 seats for Harijans, 1 seat for Anglo Indians & Indian Christians, and 1 seat for Muslims.

- In 1950, Srimati Champakam Dorairajan, a Brahmin candidate, filed an application to High Court of Madras under Article 226 of Indian Constitution, complaining of a breach of her fundamental right to get admission into educational institutions maintained by the state.

- The High Court of Madras delivered its judgement and ruled in favor of Champakam Dorairajan.

- State of Madras appealed this ruling in Supreme Court and thus the case came before the Supreme Court of India.

Issues before the Court:

- The main issue before the court was whether the Communal G.O. of 1927, which provided for reservation in admission to educational institutions based on religion, race and caste, was in violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed to the citizens of India under Article 15(1) and Article 29(2) of the Indian Constitution.

- Article 15(1) of the Indian Constitution prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them. It states that “the State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.”

- Article 29(2) of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right of any section of citizens to conserve their distinct language, script or culture. It states that “no citizen shall be denied admission into any educational institution maintained by the State or receiving aid out of State funds on grounds only of religion, race, caste, language or any of them.”

- The State of Madras argued that the provisions of these articles have to be read along with other articles in the Constitution, particularly Article 46 which charges the State with promoting the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and protecting them from social injustice and exploitation.

Judgment:

- The Supreme Court held that the Communal G.O. of 1927 constituted a violation of the fundamental right guaranteed to the citizen of India by Article 29(2) of the Constitution and was therefore void under Article 13.

- Article 13 of the Indian Constitution describes the means for judicial review. It enjoins a duty on the Indian State to respect and implement the fundamental right. And at the same time, it confers a power on the courts to declare a law or an act void if it infringes the fundamental rights.

- The Court held that the directive principles of State Policy laid down in Part IV of the Constitution cannot in any way override or abridge the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III.

- The Court held that the classification in the said Communal G.O. proceeds on the basis of religion, race and caste and is opposed to the Constitution and constitutes a clear violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed to the citizen under Article 29 (2).

Legacy:

- The Supreme Court’s judgement in Smt. Champakam Dorairajan v/s State of Madras case held that the Communal G.O. of 1927, which provided for reservation in admission to educational institutions based on religion, race and caste, was in violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed to the citizens of India under Article 15(1) and Article 29(2) of the Indian Constitution.

- The judgement of the Supreme Court led to the first amendment of the Indian Constitution, which added Clause (4) to Article 15, and also brought clarity to the relationship between the directive principles of State Policy and the fundamental rights under the Indian Constitution.

- Clause (4) to Article 15 allows the State to make special provisions for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens, or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

This article is part of the series “Landmark Judgements that Shaped India” under the Indian Polity Notes & Prelims Sureshots. We aim to make the articles comprehensive while leaving out unnecessary information from the UPSC perspective. If you think this article is useful, please provide your feedback in the comments section below.