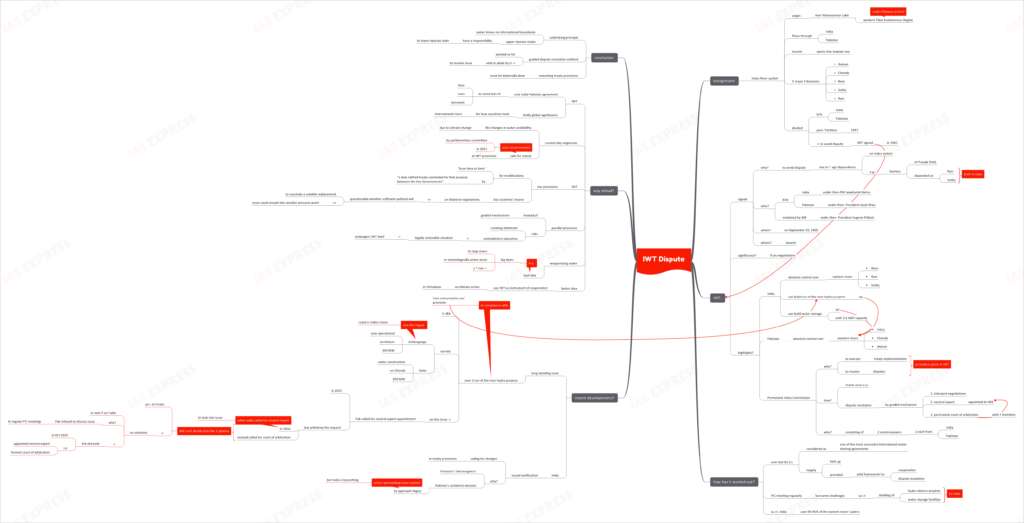

Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) Dispute – Background & Recent Developments

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

Recently, Pakistan took a dispute under the IWT to the Hague while India issued a notification to Pakistan calling for a relook at the treaty terms. This has opened up conversation about the future of the landmark treaty.

Background:

- The Indus River system originates near the Manasarovar Lake in western Tibet Autonomous Region, an area notably under Chinese control.

- It flows through India and Pakistan before emptying into the Arabian Sea.

- It has 5 major tributaries:

- Jhelum

- Chenab

- Beas

- Sutlej

- Ravi

- The 1947 Partition divided the Indus River Basin between India and Pakistan. To avoid dispute, the landmark Indus Water Treaty was signed in 1960.

What is the treaty about?

- This treaty was concluded on September 19, 1960, in Karachi, between India (under then-PM Jawaharlal Nehru) and Pakistan (under then- President Ayub Khan) to give the former, control over the eastern rivers and the latter, control over the western rivers.

- The treaty was mediated by the World Bank (under then- President Eugene R Black).

- The treaty was concluded to avoid dispute arising from the countries’ farming communities’ high dependence on the Indus waters. For instance, the farmers of Pakistan’s Punjab province were dependent on Ravi and Sutlej, both of which are in India.

- It took 9 years of negotiations, to conclude the terms:

- India has absolute control over the “eastern rivers”:

- Beas

- Ravi

- Sutlej

- Pakistan has absolute control over the “western rivers”:

- Indus

- Chenab

- Jhelum

- India can build run-of-the-river hydropower projects on the western rivers and build 3.6 MAF water storage capacity.

- Creation of the Permanent Indus Commission to oversee the treaty’s implementation and resolve disputes.

- It meets at least once a year.

- It has 2 commissioners- one each from the two countries.

- Distinct procedures have laid out to guide the commission’s functioning.

- Intergovernmental negotiations is the 1st stage of dispute resolution.

- In case of continuing differences, a Neutral Expert is to be appointed by the World Bank.

- As a last resort, disputes are referred to a Court of Arbitration consisting of 7 members. This court is also to be appointed by the World Bank.

- India has absolute control over the “eastern rivers”:

How has it worked out so far?

- The IWT continues to be considered as one of the most successful international water sharing agreements. It has largely held up and provided a solid framework for cooperation and dispute resolution.

- The PIC has been meeting regularly, despite bilateral tensions. For instance, New Delhi initially decided not to attend the PIC meeting, following the 2016 Uri attack, but later reversed its decision in 2017.

- There have been some challenges to the implementation of the treaty, such as disputes over the construction of hydro-electric projects and water storage facilities by India.

- Currently, India uses some 94-95% of the eastern rivers’ waters. The remaining flows into Pakistan.

What are the recent developments?

- One of the longstanding disputes between the two countries is the one over 2 hydroelectric power projects in J&K-

- The now-operational Kishenganga, a 330 MW project on the Jhelum River

- The under-construction Ratle project, a 850 MW project on the Chenab River

- Both are run of the river projects i.e. in compliance with the treaty provision for “non-consumptive use” of the western tributaries’ waters by India.

- However, Pakistan has been objecting to these projects. Also, the Kishenganga project was constructed after the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled in India’s favour.

- Islamabad asked World Bank to appoint a neutral expert to look into the dispute in 2015. This request was then retracted in 2016. It instead called for a Court of Arbitration to adjudicate the matter.

- On the other hand, New Delhi asked World Bank to appoint a neutral expert to look into the matter.

- The treaty doesn’t empower the World Bank to decide the precedence of the procedures, the process was put on pause in 2016.

- Over the next 5 years, efforts to arrive at a solution failed as Pakistan persistently refused to use the regular PIC meetings to discuss the issue.

- In October 2022, the World Bank went ahead and did both- appointed a neutral expert and constituted a court of arbitration.

- Citing Pakistan’s ‘intransigence’ (refusing to compromise/ change position) with regards to these two projects, India wrote to Pakistan calling for changes in the treaty provisions.

- India also criticized Pakistan’s decision to approach the Hague as a ‘unilateral’ decision. While the court has started hearing the case, India is boycotting the proceedings.

What is the way ahead?

- The IWT has stood the test of time as the only India-Pakistan agreement to withstand the pressure of wars and terrorism. It is also holds global significance for how countries treat international rivers.

- The current day exigencies, like the changes in water availability as a result of climate change, call for a relook at the IWT provisions. In 2021, even a parliamentary committee recommended renegotiation of the treaty.

- The treaty has provisions for modifications ‘from time to time’. However, this must be done by “a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two Governments”.

- However, given the countries’ record on bilateral negotiations, it is questionable whether sufficient political will can be mustered to conclude a suitable replacement for the IWT.

- It is a concern that this issue will morph into another pressure point in the bilateral ties, with increasing frequency of accusations from Pakistan that India has ‘turned off the water’ and of comments from India, like ‘blood and water cannot flow together’.

- Parallel processes, as opposed to the treaty’s graded mechanism, risks creating a stalemate. It could result in contradictory outcomes, creating a legally untenable situation. This could endanger the 62-year old treaty itself.

- Going forth, it is to be remembered that weaponizing water is a bad idea. For instance, India would face major challenges if it decides to build big dams to stop the western rivers from entering Pakistan, especially given the seismologically active nature of the Himalayan region.

- Treating the treaty as an instrument for India-Pakistan collaboration on climate action in the Himalayan region is a much better idea.

Conclusion:

The underlying principle of IWT is that water knows no international boundaries and upper riparian states have a responsibility to lower riparian state. The graded dispute resolution method has worked so far. It is vital to abide by the treaty’s terms in resolving the issue. Reworking the treaty provisions must be a bilateral exercise.

Practice Question for Mains:

Discuss the success of the Indus Water Treaty over the past 62 years. What are the challenges going forth? (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.