The Necessity of Discoms- Should India Dismantle its Discoms

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

Intro:

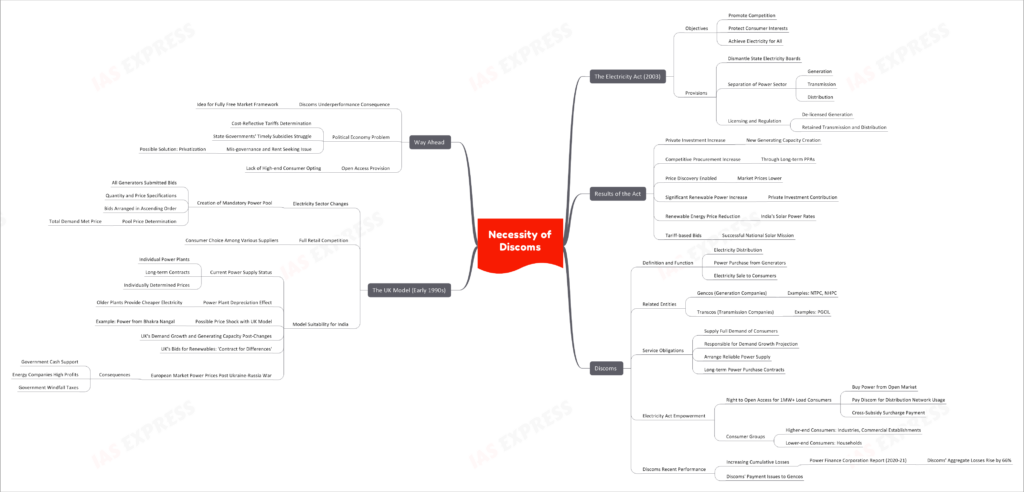

The accumulating losses faced by the Indian discoms have been rising in the past few years. In this backdrop, there have been calls to dismantle the concept of discoms and opt for a de-regulated model along the lines of the UK model.

The Electricity Act:

- The 2003 Electricity Act was passed with the objective of:

- Promoting competition

- Protecting consumer interests

- Achieving electricity for all

- The Act provided for the dismantling of State Electricity Boards.

- It also provided for the separation of generation, transmission and distribution segments of the sector into separate companies.

- While electricity generation was de-licensed, licensing and regulation were retained for transmission and distribution.

What have been the results?

- There has been a rapid increase in the share of private investment in new generating capacity creation.

- Competitive procurement through long-term PPAs (power purchase agreements) has increased.

- It has enabled price discovery. Prices in the market have been lower than lower than those anticipated under the earlier cost-plus dispensation used for determining tariffs.

- It has also led to a significant increase in renewable power in the energy mix. The increasing private investment is a key contributor to this trend.

- It has also made renewable energy cheaper. For instance, India now boasts one of the cheapest rates for solar power in the world.

- The tariff-based bids for electricity supply to the discoms has been key to the success of the National Solar Mission.

Discoms:

- Discoms or distribution companies are utility companies tasked with electricity distribution. They purchase power from the electricity generators (like the power plants) and sell them to the consumers.

- The generating entities are called gencos/ generation companies. Eg: NTPC, NHPC.

- Transmission is done by transcos/ transmission companies. Eg: PGCIL.

- Discoms have a universal service obligation to supply electricity to meet the full demand of consumers in its license area. Hence, it is responsible for projecting demand growth and arranging for reliable power supply.

- Discoms do this by entering into long-term power purchase contracts (PPAs).

- The Electricity Act empowers consumers with a load of 1MW and above with the right to open access.

- This means that such consumers aren’t forced to buy power only from the local discom. They can purchase cheap power from the open market.

- They need to pay the discom only for using their distribution network and a cross-subsidy surcharge.

- This surcharge became necessary as the higher-end consumers (industries and other commercial establishments) pay more and cross-subsidise the lower-end consumers (households).

- In the recent years, discoms are seen as the weak link in the power supply chain.

- This is because of the increasing cumulative losses. For instance, a report by the Power Finance Corporation noted that the discoms’ aggregate losses had risen by 66% to 50,281 crore INR in 2020-21.

- There is also the issue of discoms being unable to pay gencos on time.

The UK Model:

- In the early 1990s, the UK made changes to its electricity sector.

- It created a mandatory power pool to which all generators submitted bids for the following day. These bids specified the power quantity and price.

- These bids were then stacked in an ascending order (price-wise) and the price with the quantity at which the total demand would be met was set as the pool price.

- This is like the intersection of supply and demand curves to arrive at the market price.

- Full retail competition was introduced and the consumers were able to choose from among the various suppliers in the market.

Would this model suit India?

- In India, power continues to be supplied by individual power plants, as per long-term contracts, at individually determined prices.

- Over time, the power plant depreciates i.e. fixed capital cost declines as a component in the tariff. As a result, older plants provide cheaper electricity.

- If the UK power pool model is adopted, all electricity would be sold at the price from the most expensive plant at which demand would be met. This would create an untenable price shock.

- For example, power from Bhakra Nangal, which is sold at few paise/ unit, would be sold at >₹4/ unit.

- Also note that the UK didn’t see any significant demand growth and consequently, the need for new generating capacity after the introduction of these changes.

- In pursuit of their energy transition goals, the country had to invite bids for renewables through ‘contract for differences’. These contracts assured the payment of the difference between the market price and the bid price when the former falls below the latter.

- In the recent times, the power prices in European market shot up in the wake of the Ukraine-Russia War. The consequences:

- The government gave cash support for lifeline consumption.

- The energy companies realized record high profits.

- Then the government had to impose windfall taxes on these profits.

- Hence, the decision makers in India didn’t opt for deregulation.

What is the way ahead?

- As a result of the discoms’ underperformance, the idea of doing away with discoms and bringing in a fully free market framework has been gaining currency.

- However, the actual problem lies in the domain of political economy.

- The regulators are unable to determine cost-reflective tariffs and the state governments struggle to give timely subsidies as mandated by law.

- There is also the issue of mis-governance and rent seeking. In such cases, privatization may be a solution.

- Despite the provision for open access, many high-end consumers aren’t opting for it.

- While the Electricity Act has mandated the State Electricity Regulatory Commissions to reduce the cross subsidy surcharge progressively, this hasn’t been done. As a result, the surcharge continues to remain a barrier.

- At the margins, gencos may have the capacity to generate power over and above the amount required by their existing contracts. Similarly, discoms face situations of surpluses as well as shortages. Here, power exchanges are enabling trading and optimum utilization of the country’s total generating capacity.

- However, volatile exchange prices are a challenge, though an expected phenomenon, considering how power demand is inelastic in nature. This has necessitated price caps.

- Meanwhile, investment in generating capacity is mainly taking place on the strength of long term contracts with discoms. As these purchase agreements are implicitly backed by state guarantee, the financing, equity and debt are de-risked.

- Also, the transition to renewables is accelerating and the power supply reliability is increasing. This too is partly a consequence of discoms projecting demand and finalizing PPAs to meet this demand.

- Hence, doing away with discoms would mean a dent in both these positive trends. We may go back to the era of power shortages.

- In short, it is necessary to think through the consequences of implementing ‘reforms’ undertaken by the West as a panacea for the challenges faced in the Indian context.

Conclusion:

While market de-regulation is considered as one of the best way to realize competitive prices and quality supply, it is necessary to consider the complexities of Indian energy market. Doing away with discoms is unlikely to be the quick-fix as imagined.

Practice Question for Mains:

Given the significant losses faced by discoms, evaluate the dismantling of discoms as a solution to India’s power supply challenges. (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.