1.4 The English and the French East India Companies

I. Introduction

Chronological Arrival of the Companies

- English East India Company: The English East India Company, originally known as “The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies”, was formed in 1600. Driven by the immense trade prospects in the East, particularly in spices, textiles, and indigo, the company sought a charter from Queen Elizabeth I. On December 31, 1600, the Queen granted a Royal Charter, allowing the company exclusive rights to English trade in the East Indies for 15 years.

- French East India Company: France entered the Eastern trade a little later than England. Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister to Louis XIII, recognized the lucrative opportunities in the East. Thus, in 1664, he chartered the French East India Company, known in French as “La Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales”. This move aimed to compete with the already established Dutch and English trading entities in the region.

Primary Intentions of the Companies

- English East India Company:

- Trade: The primary goal was trade. They sought Indian spices, such as pepper, cloves, and nutmeg, which were in high demand in Europe. Indian textiles, especially cotton and silk, also attracted European traders.

- Monopoly: While trade was the primary focus, the company aimed to establish a monopoly over the trade routes and eliminate competitors. The Royal Charter granted them the exclusive rights to conduct trade, ensuring they could dominate the market and reap maximum profits.

- Territorial Expansion: Although initially not a primary objective, over time, the company sought territorial control. By controlling territories, they could manage production, regulate trade, and extract revenues.

- French East India Company:

- Trade: Like the English, the French were lured by the prospects of spices, textiles, and other exotic goods from the East. They hoped to tap into the lucrative market and bring the goods back to Europe.

- Counterbalance: Recognizing the growing influence of the English and Dutch in the East, the French company’s establishment also aimed to serve as a counterbalance. They hoped to break the monopolies and establish their own foothold.

- Diplomacy and Alliances: The French, in many instances, were more open to forming alliances with local rulers and engaging in diplomatic endeavors. This was seen in their interactions with various sultans and rulers of the Deccan and other regions.

The inception of both the English and French East India Companies marked the start of intense European competition in India. While the quest began with trade, it eventually transformed into a political and territorial struggle, shaping the history of India in the centuries to come.

II. Foundations of the English East India Company in India

Early Charters and Privileges Granted by the British Crown

The English East India Company was a pioneer in establishing a structured trade regime in India. Given the challenges faced due to overseas trade and competition, the British Crown saw the importance of formalizing this venture through a series of charters. These charters essentially solidified the position of the English East India Company in the Asian trade market and provided it with unparalleled advantages.

- 1600 Royal Charter: This was the initial charter provided by Queen Elizabeth I on December 31, 1600. This significant move allowed “The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies” exclusive rights to carry out trade in the East Indies for a span of 15 years. This exclusivity meant that no other English entity could legally trade in that region, giving the company a clear competitive edge.

- Subsequent Charters: As the company gained momentum and faced growing competition, especially from the Dutch and later the French, the British Crown issued subsequent charters. These were not only renewals of the original charter but often came with additional privileges. The terms often included the ability to wage war, form alliances with local rulers, and establish fortified trading posts.

Trading Posts: Establishment in Surat, Madras (Chennai), Bombay (Mumbai), and Calcutta (Kolkata)

Each trading post the company established marked a significant step in the consolidation of its influence in India. The decision to set up these posts was influenced by the strategic importance of locations, potential trade volume, and the political environment of the region.

- Surat: Recognized as the primary gateway for trade, the English East India Company established its first factory in Surat in 1612. This western port city offered a vantage point to control the sea routes and access the rich hinterland. Surat quickly became the hub for trading commodities like textiles, especially fine cotton, and spices.

- Madras (Chennai): In 1639, the company moved down the Coromandel Coast and found a new trading opportunity in Madras. A piece of land was acquired from a local ruler where they built Fort St. George. Over time, this fort turned into a fortified city and became a vital trade and administrative center. Madras specialized in the cotton and muslin trade.

- Bombay (Mumbai): The story of Bombay’s acquisition is quite fascinating. It was ceded to England in 1661 as part of the dowry when King Charles II married Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess. By 1668, the control of Bombay was handed over to the East India Company. The natural harbor and strategic location turned Bombay into an essential trading town, especially for the western coast of India.

- Calcutta (Kolkata): The establishment of a trading post in Calcutta in the late 17th century marked the company’s push into the fertile Bengal region. Located on the banks of the Hooghly River, it was initially just a trading post. However, given the abundance of the region in jute, indigo, and fine muslin, Calcutta soon rose to prominence.

The Rise of Calcutta as a Significant Trading Hub

Calcutta’s significance in the trade map of the English East India Company cannot be understated. While the initial setup was humble, the potential was quickly recognized.

- Geographical Advantage: Calcutta’s position near the Bay of Bengal and along the Hooghly River made it strategically important. This allowed ships to anchor close and facilitated easier transport of goods from the hinterland.

- Bengal’s Rich Produce: The fertile plains of Bengal were known for their rich produce. From jute to indigo and the fine muslin, which was in high demand in Europe, the region was a goldmine for traders.

- Administrative Relevance: As trade grew, so did the need for a structured administration. Calcutta soon became not just a trade center but also an administrative hub. The establishment of Fort William in the early 18th century marked this transition. This fortification ensured the company could safeguard its interests against potential threats.

- Cultural and Social Impact: The rise of Calcutta as a trading hub also led to its cultural evolution. With traders, administrators, and other officials coming in from England, the city saw a blend of cultures. Over time, it not only emerged as an economic hub but also a center for education, art, and culture in India.

The English East India Company’s journey, from acquiring charters to establishing significant trading posts across India, reflects its vision and adaptability. While the initial goal was purely trade, the eventual intertwining of commerce, politics, and culture shaped India’s history in ways that still resonate today. Calcutta’s rise epitomizes this journey, where a trading post became a city of global importance.

III. Foundations of the French East India Company in India

While the English East India Company established its roots in India, parallely the French also ventured into the Indian subcontinent with a similar quest for trade and influence. The emergence of the French East India Company is marked by its distinct history, strategic establishments, and several internal issues that set it apart.

Establishment under Cardinal Richelieu

The inception of the French East India Company, or “La Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales”, took place in 1664 under the patronage of Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister to King Louis XIII. Richelieu recognized the significance of trade in the East and the potential economic and political benefits it could bring to France. Under his guidance:

- The company received exclusive rights to trade with the East for a period of fifty years.

- It was endowed with a host of privileges including tax exemptions and the authority to establish colonies.

- The company, bolstered by the Crown’s support, aimed to rival the established English and Dutch companies in the region. Richelieu’s vision was to bolster French influence overseas and ensure a steady influx of commodities, most notably spices, textiles, and indigo.

Key centers of influence

The French, just like their European counterparts, established various trading posts across the Indian subcontinent. Some of the pivotal ones included:

- Pondicherry (Puducherry): Acquired in 1674, Pondicherry became the cornerstone of French ambitions in India. The town was a vital trade center and soon blossomed into the administrative and political hub for the French in India. The French architectural influence can still be seen in the city’s design and structure, showcasing the lasting legacy of their presence.

- Mahe: Situated on the Malabar Coast, Mahe was strategically significant for the trade of spices and wood. Secured by the French in 1725, it allowed them access to the rich trading ports of the western coast.

- Karaikal: Located south of Pondicherry, it was annexed in 1739. The fertile land here was ideal for cultivation, especially rice, which became a primary export.

- Yanam: Another acquisition on the eastern coast in 1723, Yanam was crucial for the French due to its proximity to key water routes.

- Chandernagore (Chandannagar): Positioned on the banks of the Hooghly River in Bengal, it was established in 1688. As Bengal became a principal trading zone, Chandernagore grew in importance for its trade in textiles.

Internal issues: Frequent reestablishments and changes in the company’s objectives

The French East India Company’s journey in India wasn’t without challenges. A number of internal issues marked its history:

- Frequent Reestablishments: The French East India Company underwent numerous reestablishments. Initially founded in 1664, it was reconstituted several times. The company was dissolved and renewed multiple times in 1719, 1720, and 1769 due to financial crises and administrative difficulties.

- Changing Objectives: The company’s objectives weren’t static. While the initial aim was trade, over time, as the geopolitical scenario of India evolved with the decline of the Mughal Empire, the French ambition swayed towards territorial control and political influence. This shift was also a reflection of the rivalry with the English, as both nations vied for dominance in India.

- Administrative Challenges: The company faced several management and administrative difficulties. Decision-making often oscillated between the company’s directors in France and its representatives in India, leading to inconsistent strategies.

- Economic Strains: Financial mismanagement, competition with English and Dutch companies, and wars in Europe strained the company’s resources. These issues, coupled with changes in European demand for Indian goods, impacted the company’s profitability.

IV. Trade and Economic Interests

Commodities and goods traded by both companies

- English East India Company (EIC) Goods: The EIC was heavily involved in the procurement of a variety of Indian goods. This included:

- Spices: Cardamom, black pepper, and cloves were among the primary spices traded.

- Textiles: Fabrics like muslin from Dhaka and chintz from Masulipatnam held great demand.

- Indigo: Primarily from the regions of Bengal and Bihar.

- Tea: While initially not sourced from India, by the 19th century, Assam became a major producer.

- Opium: Grown especially in the Malwa and Bihar regions, and later became a controversial commodity due to the Opium Wars with China.

- French East India Company Goods: The French company, while sharing some similarities in trade interests with the EIC, had its unique array of commodities.

- Spices: Like the EIC, spices formed a large portion of their trade.

- Textiles: Fine fabrics, especially from areas around Pondicherry.

- Coffee: Primarily sourced from the Malabar region.

- Rice: Especially from areas surrounding their establishments like Karaikal.

- Pearls: The Coromandel coast was a known region for pearl diving.

Impact on Indian handicrafts and textile industries

- Handicrafts:

- The demand from Europe led to an increase in the production of handicrafts.

- However, the introduction of machine-made goods from Europe began to overshadow the traditional handicraft industry.

- Artisans faced stiff competition, often leading to a decline in certain sectors, such as metalwork and pottery.

- Textile Industries:

- Initially, Indian textiles enjoyed immense popularity in European markets.

- Bengal’s Muslin, in particular, was highly sought after for its finesse and quality.

- However, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, machine-made textiles began flooding Indian markets.

- This led to the gradual decline of traditional weaving sectors, with many weavers losing their livelihoods.

Import and export dynamics with Europe

- Imports:

- Both companies brought in commodities to cater to the Indian market and secure their trade relations.

- Items included fine wines, European fashion items, metals, and firearms.

- Firearms and ammunition, in particular, played a pivotal role in helping these companies establish and expand their footholds in India.

- Exports:

- Indian goods, given their unique nature and quality, had a significant demand in European markets.

- While textiles, spices, and indigo were regularly exported, other items like saltpeter (used in gunpowder) were also in demand, especially by the EIC.

- The dynamics of trade shifted over time, especially with Europe’s industrial advancements. By the late 18th century, there was a noticeable decline in the export of traditional Indian handicrafts.

Emergence of trading monopolies and their implications for the Indian economy

- Emergence:

- Both the English and French East India Companies were granted trading monopolies in their respective regions by their governments.

- The EIC’s Regulating Act of 1773 and the Pitt’s India Act of 1784 gave it significant control over trade in India.

- Similarly, the French company, under decrees like those in 1719 and 1720, ensured its dominant position in its areas of influence.

- Implications:

- With the establishment of trading monopolies, traditional Indian merchants found it challenging to compete.

- Price manipulations, especially in the procurement of raw materials, adversely affected local producers.

- The monopolistic practices also led to the deindustrialization of certain sectors in India, especially textiles.

- The drain of wealth is another significant aspect. As these companies funneled profits back to their home countries, it led to a significant outflow of Indian wealth to European shores.

- The monopolistic controls further paved the way for political controls, as these companies gradually transitioned from mere traders to rulers, shaping the colonial history of India.

The trade and economic interests of both the English and French East India Companies deeply influenced the socio-economic landscape of India. While they brought certain commodities and cultures to the subcontinent, their overarching control and monopolistic practices also had several negative repercussions, which would shape India’s economic and political trajectory for centuries to come.

V. Diplomatic Relations and Alliances

English Company’s relationships with Mughal emperors and regional rulers

- Initial Interactions: The English East India Company (EIC) commenced operations in India during the rule of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. Sir Thomas Roe, who visited Jahangir’s court from 1615-1618, secured a favorable trading position for the EIC.

- Challenges and Growth: As Mughal authority waned, especially post-Aurangzeb in the early 18th century, regional powers grew in prominence. The EIC had to navigate complex alliances and enmities, often resulting in military confrontations.

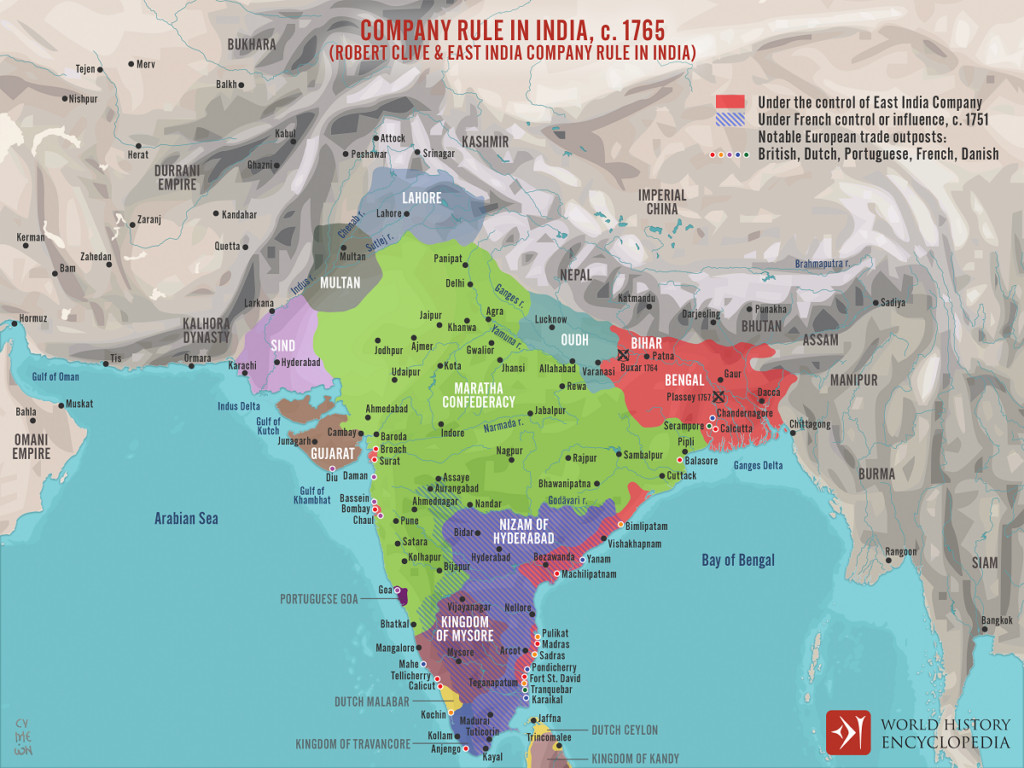

- Bengal Relationship: The Battle of Plassey in 1757 marked a turning point. Through cunning diplomacy and military might, Robert Clive managed to defeat Siraj ud-Daulah, bringing Bengal under EIC influence.

- Maratha Diplomacy: The Maratha Empire posed a significant challenge to the EIC. Diplomatic endeavors led to the Treaty of Bassein in 1802, a decisive arrangement that brought large Maratha territories under EIC control.

- Relationship with Tipu Sultan: In the south, the EIC faced Tipu Sultan of Mysore. The four Anglo-Mysore wars spanning from 1767 to 1799 showcased the company’s blend of military strategy and diplomacy. Tipu’s resistance eventually ended with his death in 1799 during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War.

- Hyderabad and Nizam: The Nizams of Hyderabad initially allied with the EIC against Tipu Sultan. However, post-1798, the Nizam became a subsidiary ally, leading to a diminished sovereignty and increased EIC influence.

French diplomatic endeavors with the Deccan sultans and other regional powers

- Initial French Presence: François Bernier, a French physician and traveler, was one of the earliest Frenchmen to build relationships in Mughal India during Aurangzeb’s time.

- Deccan Diplomacy: The French were primarily based in the Deccan and Pondicherry. They built strong relationships with the Deccan sultans, especially with the Nawab of Arcot.

- Alliance with Tipu Sultan: Unlike the English, the French saw an ally in Tipu Sultan. Together, they attempted to counteract EIC’s growing influence. The French provided military assistance, especially in the form of trained soldiers and modern weaponry.

- Pondicherry and its Surroundings: French territories around Pondicherry became hubs of diplomacy. Dupleix, the Governor-General of French India, was particularly instrumental in establishing relationships with local rulers.

- Tussle with English: French diplomatic relations often had to contend with English interventions. For instance, the Battle of Wandiwash in 1760 between the English and the French, alongside their respective allies, showcased the constant struggle for dominance.

Differences in diplomatic strategies: English pragmatism versus French idealism

| Aspect | English Pragmatism | French Idealism |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Approach | Trade-centric, securing favorable positions through charters and negotiations. | Focus on establishing strong cultural and political relationships. |

| Major Alliances | Mughal Emperors, Marathas, Nawabs of Bengal, Nizams of Hyderabad. | Deccan Sultans, Tipu Sultan. |

| Military Strategy | Combine force with negotiation, often leading to direct rule. | Offer military support as allies, focusing on mutual benefits. |

| Long-term Goals | Establishing dominance and direct governance, leading to colonization. | Fostering long-term alliances and shared interests. |

| Response to Challenges | Adaptability, changing strategies based on regional dynamics. | Maintain established relationships, even against rising odds. |

VI. Socio-Cultural Impacts

Introduction of European lifestyles, cuisines, and architecture in India

- The establishment of European colonies in India led to the introduction and spread of various European lifestyles. The European settlers brought with them unique tastes in music, fashion, and art, which gradually melded with traditional Indian styles, creating an amalgam of cultures.

- European cuisines, too, found their way into India, enriching the Indian palate. Dishes such as cakes, puffs, and custards became popular, especially in regions with a pronounced European presence. Many of these dishes have been Indianized, resulting in a unique blend of flavors. Examples include the “Anglo-Indian curry” and the “Kolkata cutlet,” which have roots in British cuisine but are distinctly Indian in taste.

- European architecture significantly influenced Indian cityscapes. One can witness this in cities like Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, and Pondicherry, where Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque architectural styles are evident. The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata and the Gateway of India in Mumbai are stellar examples of this architectural amalgamation.

Role in promoting English and French languages and education

- English and French became vital languages of communication in regions under their respective colonial powers. English, especially, became the medium of instruction in many schools and colleges, laying the foundation for its widespread use in India today.

- The establishment of English-medium institutions like the University of Calcutta in 1857, University of Mumbai in 1857, and University of Madras in 1857 played a pivotal role in promoting English-based education. These universities not only trained Indians in the English language but also introduced them to Western science, arts, and literature.

- French influence was predominant in parts of South India, especially Pondicherry. The French established institutions where French was the primary medium of instruction. The introduction of French in Indian schools led to the emergence of a distinct Indo-French culture, which thrives in certain pockets of the country even today.

Interactions with Indian society: Marriage alliances, cultural exchanges, and adoption of Indian customs

- As Europeans settled in India, there were inevitable interactions with the local populace. Many Europeans, especially those who came in the early days of colonial expansion, formed marital alliances with Indians. These marriages, often between European men and Indian women, resulted in the birth of the Anglo-Indian community, which has its distinct culture and traditions.

- Cultural exchanges were not limited to marriage. Europeans were fascinated by Indian music, dance, art, and philosophy. The Bhagavad Gita, for example, was translated into English and other European languages, attracting the attention of philosophers and thinkers like Aldous Huxley and J.D. Salinger.

- Many Europeans adopted Indian customs and practices. They took to wearing Indian attire, enjoyed Indian food, and even practiced Indian religions. An example is Sister Nivedita, an Irish teacher who became a disciple of Swami Vivekananda and played a crucial role in promoting Indian nationalistic ideals.

- On the flip side, Indians began to adopt European customs and lifestyles. This was especially evident among the Indian elite, who began to dress in European fashion, send their children to English-medium schools, and even adopt European etiquette and mannerisms.

- Festivals and celebrations became moments of shared joy and camaraderie. Christmas, for instance, began to be widely celebrated in regions with significant European populations. Conversely, many Europeans took part in Indian festivals like Diwali and Holi, embracing the spirit of these occasions.

VII. Administrative Structures and Policies

The English Company’s Shift from Trading to Ruling

The transition of the English Company from a mere trading entity to a dominant ruling power in India is a profound chapter in the history of the subcontinent. This transition wasn’t abrupt but rather an evolutionary process that was characterized by a series of historical events, strategic decisions, and evolving administrative structures.

- Evolution of Dual Governance

- The Battle of Plassey in 1757 and the Battle of Buxar in 1764 were pivotal in establishing the British foothold in India. These victories allowed them to impose their administrative and revenue policies on vast territories.

- Post these triumphs, the British Crown endorsed the company’s territorial gains, leading to the formalization of dual governance, commonly referred to as the “Diarchy.”

- British Authority: Was more symbolic, with the company holding the actual reins. They were responsible for the administration, judiciary, and revenue collection.

- Indian Rulers: Though they retained their titles and some administrative responsibilities, their roles were largely ceremonial. Their powers were drastically curtailed, and they operated under the watchful eyes of the English representatives.

- This system was a clever strategy by the company to leverage the legitimacy of the existing rulers while exerting control and reducing potential resistance.

- Revenue Collection Systems

- The English Company’s main motivation behind its interest in India was economic. Hence, the introduction of systems that maximized revenue was a priority.

- Permanent Settlement of 1793: Instituted by Lord Cornwallis, it aimed at streamlining revenue collection in Bengal. Land was leased to zamindars or landlords at fixed rates, making them responsible for collecting and depositing the revenue. This system assured the company of a consistent revenue flow but often burdened the peasants.

- Ryotwari System: Introduced primarily in parts of Madras and Bombay, this system bypassed the zamindars. Instead, the peasants or ryots had a direct agreement with the company, offering more favorable terms to the cultivators but also binding them to pay revenue directly.

- Mahalwari System: This was a blend of the above two systems and was implemented in parts of North and Central India. Here, a group of villages or a mahal collectively paid the revenue.

The French Company’s Administrative Setup and Revenue Policies

While the British were making significant inroads in India, the French, too, had their territories and aspirations. The French East India Company, founded in 1664, was the instrument through which France exerted its influence in the Indian subcontinent.

- Administrative Structure

- The French territories in India, such as Pondicherry, Mahe, Karaikal, and Chandernagore, were collectively known as the “French Establishments in India.”

- Governor-General: Was the topmost authority in these territories. He was responsible for the overall administration, defense, and foreign affairs of the French possessions.

- The local administration was overseen by Governors, who were stationed at each of the French establishments. They ensured the smooth functioning of the territories and reported to the Governor-General.

- Revenue Policies

- The French, like the British, understood the importance of a streamlined revenue collection system. Their policies, however, were a bit different.

- Unlike the English Company’s approach of imposing their own systems, the French often relied on local customs and practices to collect revenue. This method was seen as more lenient and flexible.

- Land Taxation: Was the primary source of revenue. The rates were often decided upon after discussions with local leaders, ensuring a certain level of fairness.

- The French also promoted agriculture and trade in their territories, which indirectly bolstered their revenue. The cultivation of cash crops and the promotion of indigenous industries were encouraged.

VIII. Religious Interactions and Missions

The realm of religion in colonial India witnessed variances in how the English and the French approached its intricacies. Their interactions with local religious practices, affiliations, and the overarching philosophies were not only distinctive but had deep-rooted impacts on the socio-religious fabric of India.

English neutrality versus French proactive approach

- The English East India Company, during its early years in India, maintained a strategic distance from local religious matters. Their primary focus was on trade, and they believed that neutrality in religious affairs would foster a harmonious business environment. This approach was fundamentally non-interventionist, where the English refrained from actively promoting or opposing any religious practices.

- Contrary to the English perspective, the French, under the patronage of their rulers and influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, were more proactive. The French perceived India not just as a land of trade opportunities but also as a potential ground for spreading Christianity. This led them to have a more involved stance, where they actively engaged with the religious aspects of Indian society, promoting Christianity while understanding and often appreciating local religious practices.

French missionaries in India: Influence and legacies

- The role of French missionaries in India was multifold. They weren’t mere spiritual leaders; they became educators, linguists, and chroniclers of Indian history and culture.

- Arrival and settlements: French missionaries began pouring into India primarily in the 17th century. Places like Pondicherry, Karaikal, and other French territories became their strongholds.

- Cultural exchange: These missionaries, such as the Jesuits, made concerted efforts to understand Indian religions. They learned local languages and even translated Christian scriptures into Indian languages.

- Education: The legacy of French missionaries in the educational sphere is undeniable. They set up schools and colleges, many of which stand even today, serving as institutions of repute. Their emphasis was on imparting knowledge, blending Western education with an appreciation of Indian ethos.

- Inter-religious dialogues: French missionaries, with their deeper understanding of Indian religions, engaged in dialogues with Hindu and Muslim scholars. This led to a rich exchange of ideas, fostering mutual respect.

- Impact on art and architecture: Some churches in India, built under the guidance of French missionaries, reflect a blend of Indian and European architectural styles. This amalgamation is a testament to their integrative approach.

English Company’s stance on religion: Differences between personal beliefs of officials and the company’s official policies

- The English Company’s official stance was strictly non-religious. It was driven by a business-first philosophy, which entailed that they should remain neutral to maintain a conducive environment for trade. The Company believed that meddling in religious affairs could lead to unnecessary friction with the locals, potentially hampering trade relations.

- However, the personal beliefs of English officials in India were diverse. Many officials were devout Christians and held deep-rooted religious convictions. Their interactions with the local populace, though personal, sometimes reflected these beliefs. There were instances of officials funding the construction of churches from their own pockets or supporting missionary activities. But it’s crucial to understand that these were personal endeavors, not reflective of the Company’s policies.

- As time progressed, especially in the 19th century, the distinction between personal beliefs and official policies began to blur. With the rise of the evangelical movement in England, there was a push towards a more proactive religious approach in India. However, this was more evident post the Battle of Plassey in 1757, when the English Company transitioned from merely being traders to rulers of vast territories in India.

- This era saw a rise in missionary activities, and while the English Company’s official policy still advocated neutrality, on-ground activities were sometimes at variance. Missionary schools, colleges, and hospitals began to emerge, and while they did invaluable work in education and healthcare, they also became centers for spreading Christianity.

- It’s essential to note that the English Company never officially endorsed these activities. The divergence between the personal beliefs of officials and the company’s official policies was evident, but as the boundaries blurred, so did the distinction between personal endeavors and official patronage.

IX. Military Engagements and Fortifications

Building of forts

Historical accounts reflect that forts played a pivotal role in the colonial expansion and dominance in India. These fortifications served as administrative centers, trade hubs, and defense bastions against rival European powers and local Indian kingdoms.

Fort St. George (Madras) by the English:

- Establishment: Constructed in 1644, Fort St. George stands as the first British fortress in India. Located on the Coromandel Coast, it formed the nucleus around which the city of Madras (now Chennai) grew.

- Strategic Importance: This fortification played a central role in the British East India Company’s defense strategy. Besides its military significance, it also became an essential administrative center.

- Architecture and Features: Adorned with thick walls, battlements, and gateways, the fort was equipped to withstand sieges and artillery attacks. Within its confines, there are also several colonial structures, like St. Mary’s Church, which is the oldest Anglican Church in India.

Fort St. Louis (Pondicherry) by the French:

- Establishment: The French, eager to assert their dominance in the Indian subcontinent, built Fort St. Louis in Pondicherry in the 18th century.

- Strategic Importance: Situated on the southeastern coast, this fort was a focal point for French military and trade activities in the region. It became the foundation of the French colonial establishment in India.

- Architecture and Features: With robust walls, trenches, and fortified towers, the fort epitomized the military architectural style of the time. Its location near the sea also added a layer of natural defense against any potential threats.

Importance of naval and military strength

For European colonial powers, naval and military strength was not merely a tool for defense. It was the key to establishing and maintaining dominance over vast territories and ensuring uninterrupted trade routes.

- Naval Supremacy: Dominance over the sea routes ensured faster trade, quicker reinforcements, and a strategic advantage over rivals. Ports, dockyards, and naval bases facilitated the repair, replenishment, and refit of fleets, enabling longer voyages and expeditions.

- Land Military Might: A robust army signified a power’s ability to defend its territories, suppress revolts, and undertake expansionist campaigns. Infantry, cavalry, and artillery units formed the crux of these land forces. The introduction of gunpowder and firearms in the subcontinent by the Europeans revolutionized warfare techniques.

- Collaborations with Local Forces: European powers often formed alliances with local rulers, merging their military technologies and strategies. This collaboration enabled them to have a better foothold and navigate the complexities of Indian polity.

Key battles and skirmishes

Though the detailed accounts of battles will be covered in subsequent modules, a brief overview is pertinent to understand the scope of military engagements during this era.

- Anglo-French Wars: Spanning over several decades in the 18th century, these conflicts saw the British and French vying for supremacy in the Indian subcontinent. Notable confrontations included the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the Battle of Wandiwash (1760).

- Sea Engagements: The naval battles were as intense as the land-based ones. These clashes ensured control over strategic ports and sea routes. The Battle of Diu (1509) between the Portuguese and a combined fleet of Egyptians, Ottomans, and Gujaratis is a notable example.

- Local Resistance: Both the English and the French often faced resistance from local Indian kingdoms. These encounters were pivotal in shaping the dynamics of colonial expansion.

X. Comparison of the Two Companies

Overview of the Main Similarities and Differences

The foundation for both the English and French East India Companies was trade. Initially, they were attracted to the Indian subcontinent because of the lucrative spice trade, textiles, and other valuable goods. Over time, they diversified their trade, and their interests evolved, leading to larger territorial conquests and control.

Administration

- English East India Company (EIC): Founded in 1600, the EIC was governed by a Court of Directors, who were elected by the company’s shareholders. This hierarchical structure enabled the company to centralize decisions made in London, with India serving as the primary operational ground. The company established presidencies in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, with each presidency having its governor and council to manage regional affairs.

- French East India Company (Compagnie des Indes Orientales): Founded in 1664 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert under King Louis XIV, its administrative structure was significantly influenced by the French monarchy. The company had centralized decision-making, with the head office located in France. In India, the main base of operation was Pondicherry, which became the administrative center for other French settlements.

Trade Policies

- English East India Company: The EIC focused on securing monopolistic trade rights. They negotiated with Indian rulers for exclusive trading privileges and established fortified trading posts to protect their interests. The primary commodities they dealt with included textiles, spices, and later, opium.

- French East India Company: The French company also sought exclusive trading rights but was more inclined towards establishing diplomatic relations with Indian rulers. Their primary trade commodities were similar to the EIC, with textiles and spices dominating the scene. However, due to various internal and external challenges, they couldn’t expand their trade to the extent the EIC did.

Cultural Impact

- English East India Company: The cultural footprint of the EIC is profound. They introduced the English language, education system, and western-style administration. English became the lingua franca for administration, leading to the emergence of a new class of educated Indians. Moreover, the company also introduced railways, telegraph, and other infrastructural developments.

- French East India Company: The French left a lasting impact, especially in places like Pondicherry. French architecture, language, and education are still evident in these regions. The amalgamation of French and Indian cultures led to a unique socio-cultural landscape in the territories they governed.

Comparison Table

| Attributes | English East India Company | French East India Company |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation Year | 1600 | 1664 |

| Administrative Center | London (UK), Presidencies in India | France, Pondicherry (India) |

| Primary Trade Goods | Textiles, Spices, Opium | Textiles, Spices |

| Cultural Contributions | English Language, Railways | French Language, Architecture |

It’s pivotal to grasp that while the English East India Company had a broader and more lasting influence on India due to its vast territorial control and longer reign, the French East India Company, though limited in its territorial influence, contributed significantly to the cultural milieu of the regions they governed.

XI. Decline and Final Years

Factors Leading to the Decline of the English East India Company:

- Economic Strains:

- In the late 18th century, the company faced financial difficulties. The cost of maintaining a vast military and administrative structure in India, coupled with decreasing trade advantages, strained its finances.

- Heavy taxation in its Indian territories led to dissatisfaction and unrest among the local populace, which added to its problems.

- Administrative Failures:

- The company’s administration became increasingly corrupt. Nepotism and mismanagement were rampant, leading to a growing dissatisfaction among both the local population and officials sent from Britain.

- Military Overreach:

- Engaging in numerous battles and conflicts not only strained the company’s coffers but also spread its military thin. The vast territories it had to manage and defend became a significant challenge.

- Political Interference:

- As the company’s power grew, so did the British government’s involvement in its affairs. This meddling often conflicted with the company’s interests and led to policy inconsistencies.

- Emergence of Nationalistic Sentiments:

- By the mid-19th century, nationalist sentiments began to emerge in India. This was a direct challenge to the company’s rule and led to widespread revolts and uprisings.

Factors Leading to the Decline of the French East India Company:

- Ineffective Management:

- Unlike the English company, which was a unified entity, the French company was re-established several times. This constant restructuring resulted in administrative confusion and inefficiency.

- Insufficient Resources:

- The French crown did not back the company as robustly as the English crown did its counterpart. As a result, the French company lacked the necessary resources and funds to establish and maintain vast territories.

- External Threats:

- Regular conflicts with the British in the European theater spilled over into India. These conflicts weakened the French company’s position in India, leading to the loss of critical territories.

- Internal Dissensions:

- Differences of opinion between the company’s leadership and the French Crown led to policy paralysis. The company often found itself in a quandary, unable to make decisive moves.

English Company’s Transition to Direct British Crown Rule After the Sepoy Mutiny:

- Sepoy Mutiny of 1857:

- Widely considered the first war of Indian independence, the Sepoy Mutiny was a direct response to the company’s misrule. The revolt, although unsuccessful, marked a significant shift in how India was to be governed.

- Government of India Act, 1858:

- This act formally dissolved the English East India Company’s rule in India. In its place, the British Crown took direct control of the territories, marking the beginning of the British Raj.

- Effects of Transition:

- Establishment of a viceroy, representing the British monarch in India.

- Indian administration underwent major reforms with the aim of decentralizing power.

- Indian Councils Act of 1861 introduced a semblance of representation for Indians in governance, although it was largely symbolic.

French Company’s Dissolution and Eventual Ceding of Territories to the Indian Union:

- Limited Presence:

- By the late 18th century, the French company’s presence in India was limited to a few pockets, the most prominent being Pondicherry (Puducherry).

- Dissolution:

- The French East India Company was formally dissolved in 1769 due to its inability to compete with its British counterpart and repeated failures in India.

- French India:

- Despite the dissolution of the company, the territories it controlled in India, known as French India, remained under French control until the mid-20th century.

- Ceding of Territories:

- Post-independence in 1947, India and France entered into negotiations regarding the fate of French India. After a series of referendums in the 1950s, the territories of French India were ceded to the Indian Union, culminating in the formal transfer on 1 November 1954.

In tracing the trajectories of the two companies, it’s evident how geopolitical rivalries, administrative challenges, and emerging nationalistic sentiments played crucial roles in shaping the subcontinent’s colonial history. While the English company’s legacy is more prominent due to its larger territorial expanse and longer duration of rule, the French company’s impact, though limited in scope, remains a significant chapter in India’s rich tapestry of history.

XII. Lasting legacies of both companies on India’s economic, political, and cultural landscapes

The sprawling subcontinent of India, known for its vast resources, rich history, and diverse culture, attracted various European traders and explorers, particularly during the 17th and 18th centuries. Foremost among these were the English East India Company and the French East India Company, which were established with the primary intention of capitalizing on trade but eventually played more profound roles, impacting India’s socio-economic and political arenas. Their interventions and imprints on the country paved the way for a new epoch in India’s history: the European colonial era.

Economic Landscape

The undertakings of both these trading giants indubitably left lasting impacts on India’s economic framework:

- English East India Company (EIC):

- Monopolistic Trade Rights: The EIC secured monopolistic trade rights, ensuring that they had an exclusive handle on particular goods, primarily spices, textiles, and opium.

- Trade Posts and Fortifications: With their rights, the EIC set up numerous trading posts, which they fortified to protect their interests. Places like Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta emerged as vital trading hubs, shaping the future economic progress of these regions.

- Introducing New Crops: The EIC introduced crops like tea and indigo, reshaping agricultural patterns and creating new avenues for trade.

- French East India Company (Compagnie des Indes Orientales):

- Diversified Trade: While they couldn’t dominate like the EIC, the French company did have its share of the textile and spice trades. They also dabbled in luxury goods which were in demand in Europe.

- Regional Economic Hubs: Areas like Pondicherry, under French control, evolved into regional economic centers, benefiting from the structured trade practices the French introduced.

Political Landscape

India’s political fabric underwent significant transformations, primarily due to the EIC:

- English East India Company:

- Territorial Control: Beyond trade, the EIC shifted its focus to territorial conquests. Using both negotiation and force, it gained control over vast regions of India.

- Administrative Changes: Introducing English as the administrative language and setting up bureaucratic systems, the EIC paved the way for the British Raj.

- Military Interventions: The EIC had its private army, which played a crucial role in annexing kingdoms and maintaining control.

- French East India Company:

- Diplomatic Relations: The French approach leaned more towards forming alliances with local rulers. Their political influence was limited compared to the EIC but still noteworthy, especially in the regions they controlled.

Cultural Landscape

Both companies left indelible imprints on India’s cultural milieu:

- English East India Company:

- Education and Language: Introduction of the English language led to the emergence of a new class of educated Indians. Schools and colleges were established, following the European model.

- Infrastructure Development: Projects like railways and telegraph lines not only facilitated trade but also brought regions closer, influencing mobility and communication.

- Social Reforms: The EIC occasionally interfered in socio-cultural practices. While some interventions, like the abolition of Sati, were progressive, others were controversial and met with resistance.

- French East India Company:

- Architecture and Urban Planning: French colonies like Pondicherry are epitomes of French architectural grandeur. Their town planning and architecture stand out distinctly.

- Language and Education: The French language found its niche, especially in the territories they controlled. They also set up educational institutions following their curriculum.

Reflection on European Colonial Era Harbingers

The English and French East India Companies, despite being commercial ventures, played significant roles as the harbingers of the European colonial era in India. Their pursuit of trade expanded into a quest for territorial control, and this transition altered the trajectory of India’s history.

The English East India Company’s impact was far-reaching, eventually leading to the establishment of British rule in India. Their interventions, both positive and negative, shaped India’s socio-economic and political future for centuries.

On the other hand, the French East India Company, though lesser in its overall impact, still managed to leave lasting legacies in the regions they controlled. Their approach was less aggressive compared to the EIC, but they too played a part in heralding the European colonial phase in India.

In retrospect, while both companies ventured into India for trade, their legacies encompassed a spectrum of changes, some of which still resonate in modern India’s ethos.

- Examine the initial diplomatic strategies of the English and French East India Companies in their early engagements with Indian rulers. How did their distinct approaches influence subsequent alliances? (250 words)

- Discuss the military strategies adopted by the English and French East India Companies. In what ways did these strategies reflect their overarching ambitions in the Indian subcontinent? (250 words)

- Drawing upon the differences in English pragmatism and French idealism, analyze how each nation’s long-term goals in India were shaped by their respective diplomatic strategies and responses to challenges. (250 words)

Responses