3.1.3 Keyne’s Theory on Demand for Money | Demand for and Supply of Money

Module Progress

0% Complete

I. Introduction to Keynesian Theory on Demand for Money

Historical background: Emergence of Keynesian economics during the Great Depression

- The Great Depression (1929-1939): The most significant global economic crisis of the 20th century, marked by severe unemployment, deflation, and banking collapses. Traditional economic theories, particularly Classical economics, failed to provide adequate solutions for recovery.

- Classical Economic Theory before Keynes: This theory, based on the works of economists like Adam Smith (1776), David Ricardo (1817), and John Stuart Mill (1848), operated under the assumption that markets were self-correcting, with Say’s Law positing that “supply creates its own demand.” The belief was that in the long run, full employment would be naturally restored through price and wage flexibility.

- Keynes’ Challenge to Classical Economics: John Maynard Keynes observed that during the Great Depression, demand for goods and services could remain low even with wage and price reductions. He rejected Say’s Law and argued that aggregate demand drives economic activity, making it necessary for the government to intervene to stabilize the economy.

Keynes’ Key Works on Monetary Theory

- “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money” (1936): Published during the height of the Great Depression, this book revolutionized economics by introducing the concept of aggregate demand. Keynes argued that demand for goods, services, and money drives economic cycles, not just supply-side factors.

- Focus on Liquidity Preference: In his seminal work, Keynes introduced the concept of liquidity preference, which explains why individuals prefer holding liquid money rather than investing it. This preference for liquidity depends on the expected return on investments and future interest rates.

- Liquidity preference was Keynes’ key contribution to monetary theory, challenging the Classical view that interest rates were determined solely by the supply of and demand for loanable funds.

- Policy Implications: Keynes advocated for active government intervention through fiscal policies (public expenditure) and monetary policies (interest rate adjustments) to manage demand for money and stabilize the economy during periods of economic downturn.

Keynes vs Classical Theory: Differences in Assumptions

- Classical Assumptions: Classical economists assumed that markets are always clear, meaning all goods and services are sold, and full employment is the natural state of the economy. Their models were based on the long-run adjustments of supply and demand through perfect competition and price flexibility.

- Keynes’ Assumptions:

- Keynes argued that economies could remain in prolonged periods of underemployment equilibrium, where resources, particularly labor, remain underutilized due to insufficient demand.

- He rejected the assumption that wage and price flexibility would always restore full employment. Instead, he emphasized that wages and prices could be sticky, meaning they do not adjust quickly enough to clear markets.

- Keynes also challenged the Classical reliance on the neutrality of money, arguing that changes in the money supply and demand directly influence interest rates, investment, and ultimately, national income.

Focus on Money Demand as an Active Variable in Determining Interest Rates

- Classical View of Interest Rates: Classical economists believed that interest rates were determined solely by the supply of savings and the demand for investment. The loanable funds theory dominated this perspective, emphasizing that savings create investment opportunities.

- Keynesian View of Interest Rates:

- Keynes shifted the focus from savings to money demand as a key determinant of interest rates. His liquidity preference theory proposed that interest rates are a reward for parting with liquidity (holding cash). Individuals and businesses hold onto liquid money based on their expectations about future interest rates and returns from investment.

- Interest rates, in Keynes’ view, were a result of the interaction between the demand for money (liquidity preference) and the money supply controlled by central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of India (founded in 1935).

- Monetary policy became central to controlling interest rates, with Keynes suggesting that central banks could lower interest rates by increasing the money supply, thereby reducing liquidity preference.

Key Implications for Economic Policy

- Active Monetary and Fiscal Policy: Keynesian theory argued for active counter-cyclical policies to manage economic demand and stabilize interest rates. This marked a significant departure from Classical economics, which believed in minimal government intervention.

- Public investment was necessary to stimulate demand during downturns, with Keynes emphasizing government spending on infrastructure, welfare programs, and other public goods.

- On the monetary side, central banks needed to manage the money supply to control interest rates, promote investment, and ensure liquidity in financial markets.

- Influence on Modern Macroeconomics: Keynes’ theory laid the foundation for modern macroeconomic policy, influencing economic thought and policy-making in India post-independence, particularly in the planning era (1950s-1970s). His ideas are still central to understanding the dynamics of demand for money and the role of central banks in regulating the economy.

II. The concept of liquidity preference

Definition of liquidity preference

- Liquidity preference refers to the preference individuals have for holding liquid assets (cash) rather than investing in less liquid assets, such as bonds or stocks.

- John Maynard Keynes introduced this concept in his 1936 work, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.”

- Keynes argued that individuals and businesses hold onto money rather than investing it due to their desire for liquidity, which serves as a cushion against uncertainty in the economy.

- Money holding provides flexibility and immediate purchasing power, which can be used when better investment opportunities arise or when there are future uncertainties.

Keynes’ motive for holding money

- Keynes identified several motives for holding money, which differ from traditional theories where money was held only for transactional purposes.

- The core reason Keynes put forth for holding money is to mitigate risk and uncertainty.

- In an uncertain economic environment, holding money ensures that individuals have liquidity to deal with unforeseen expenditures or capitalize on speculative opportunities.

Role of expectations in shaping money demand

- Expectations play a crucial role in influencing the demand for money. Keynes emphasized that individuals’ expectations regarding the future significantly affect their liquidity preferences.

- Future interest rates: People’s expectations about rising or falling interest rates affect their decision to hold or invest money.

- If future interest rates are expected to rise, individuals will prefer to hold cash and wait for a better opportunity to invest.

- Conversely, if interest rates are expected to fall, people will invest in bonds now to lock in current rates.

- Income levels: Expectations about future income levels can influence liquidity preference.

- If individuals expect their income to rise, they may hold less cash, assuming they will have more liquidity in the future.

- In contrast, if they expect a reduction in income, they may hold more cash to protect against future financial uncertainty.

- Price levels: Anticipations of inflation or deflation shape the decision to hold or spend money.

- If inflation is expected, individuals will prefer to spend or invest money now before the value erodes.

- If deflation is expected, they may prefer to hold cash as prices are likely to drop, increasing the purchasing power of their savings.

Three motives for money demand

- Keynes introduced three specific motives for holding money, which reflect different reasons why individuals and firms demand liquidity in the economy.

Transaction motive

- The transaction motive represents the need for money to carry out day-to-day transactions.

- People and businesses need money to pay for goods and services as part of their regular economic activities.

- Income-expenditure link: As income increases, the demand for transactional money also rises, since higher income usually results in higher spending.

- In economies with advanced payment systems, such as India’s growth in digital transactions through Unified Payments Interface (UPI) (launched in 2016), the transaction motive can change, as less physical money is needed for transactions.

Precautionary motive

- The precautionary motive stems from the need to hold money to guard against unforeseen events or emergencies.

- In Keynes’ framework, people and businesses hold cash reserves to handle unexpected events such as medical emergencies, accidents, or sudden business expenses.

- Uncertainty and risk aversion: In an economy with higher uncertainty, such as during periods of political instability or economic downturn, people are more likely to hold money for precautionary purposes.

- The relationship between economic stability and precautionary money demand is strong. For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, uncertainty spiked, and people hoarded cash out of fear of financial collapse.

- In India, informal sectors rely heavily on cash reserves for precautionary reasons, given the lack of formal financial safety nets.

Speculative motive

- The speculative motive refers to holding money to take advantage of future changes in the value of assets like bonds, stocks, or real estate.

- Keynes argued that investors hold money to speculate on the rise or fall of interest rates, which inversely affects bond prices.

- If interest rates are expected to fall, bond prices will rise, so individuals will invest in bonds.

- If interest rates are expected to rise, bond prices will fall, and investors will hold money, waiting for a better time to purchase bonds.

- This speculative demand for money contributes to what Keynes called the liquidity trap, a situation where monetary policy becomes ineffective because people hoard money instead of investing, even when interest rates are low.

- In India, speculative motives are evident in stock market behavior, where investors often hold money in anticipation of significant Sensex (established in 1986) or Nifty movements.

Impact of income and interest rates on liquidity preference

- Income levels: Higher income levels generally lead to an increased demand for money, as individuals and businesses need more liquidity to manage larger volumes of transactions.

- However, the effect on liquidity preference also depends on the distribution of income. Wealthier individuals may not significantly increase their money demand, opting instead to invest.

- Interest rates: Interest rates have an inverse relationship with the demand for money.

- Low-interest rates: When interest rates are low, individuals prefer to hold more money (liquidity) as the opportunity cost of holding money is low.

- High-interest rates: When interest rates rise, people are more likely to invest money in bonds or savings accounts where they can earn higher returns.

- Shifts in the liquidity preference curve: Changes in income levels or interest rates cause shifts in the liquidity preference curve.

- For example, an increase in income or a decrease in interest rates would shift the liquidity preference curve outward, indicating a higher demand for money.

- A reduction in income or an increase in interest rates would shift the curve inward, reflecting a lower demand for money.

Interaction with interest rates

- The interaction between liquidity preference and interest rates is central to Keynes’ theory of money demand.

- Interest rate as a reward for parting with liquidity: Keynes argued that people demand compensation in the form of interest for giving up their liquidity.

- Interest rate elasticity: The sensitivity of money demand to changes in interest rates is critical for monetary policy. If demand is very elastic, small changes in interest rates can lead to large changes in money holding behavior.

- In the context of central bank policies, such as those of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the liquidity preference theory helps explain why lowering interest rates might not always spur investment, particularly during periods of low confidence.

III. Transaction motive in Keynesian theory

Concept of the transaction motive

- Transaction motive refers to the need for individuals and businesses to hold money for daily economic activities.

- John Maynard Keynes identified this motive as essential for carrying out regular payments for goods and services.

- This motive is distinct from other forms of money demand, such as precautionary or speculative, as it directly supports consumption and production activities.

- Liquidity is necessary to fulfill transactions in both households and businesses, ensuring the smooth functioning of an economy.

Daily economic activities requiring liquid money

- Individuals need liquid money for daily expenses like groceries, utility bills, and transportation.

- Businesses require liquidity for regular operational payments such as wages, inventory purchases, and maintenance.

- Without enough liquid money, both individuals and firms would face difficulties in meeting their short-term financial obligations, which could disrupt broader economic activities.

Factors affecting transaction demand

- Level of income: As personal or household income rises, the demand for money to conduct transactions also increases.

- The more income one has, the more goods and services they are likely to purchase, thus requiring more liquidity.

- Payment habits: Traditional payment habits, such as the use of cash, cheque, or digital payment methods, play a role in determining how much liquid money is needed.

- In economies where cash payments dominate, the transaction demand for money remains high, while in economies with robust digital infrastructure, the need for physical cash decreases.

- Development of the financial system: The strength and sophistication of a country’s financial system determine how efficiently transactions can be conducted.

- For example, in India, the rise of Unified Payments Interface (UPI) since 2016 has drastically reduced the need for physical cash, as digital transactions have become more common.

- In highly developed financial systems, people and businesses can conduct transactions with ease using a variety of tools such as credit cards, mobile wallets, and instant payment systems.

Relation to nominal income

- Nominal income refers to the income an individual or business earns without adjusting for inflation.

- There is a linear relationship between nominal income and the demand for money under the transaction motive.

- As nominal income rises, the demand for liquid money to facilitate transactions also increases proportionally.

- This relationship is integral to understanding Keynesian money demand, where income changes lead to corresponding changes in transaction money demand.

- For example, if a household’s monthly income increases from ₹20,000 to ₹40,000, their transactional demand for money will also rise in direct proportion as their consumption and expenditure grow.

Impacts of technological advancements

- Electronic banking and digital payment systems have significantly altered the nature of transaction demand in the modern economy.

- In recent decades, there has been a shift from holding physical cash for transactions to using digital banking tools.

- With the rise of net banking, mobile banking, and point-of-sale systems, the need for liquid money has reduced in many developed economies.

- In India, the introduction of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (2014), which aimed to promote financial inclusion by offering bank accounts to the unbanked, further enhanced access to electronic payments.

- Payment systems such as UPI and Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM) app allow for seamless digital transactions between individuals, businesses, and banks.

- These systems reduce the need for physical currency in daily transactions, leading to a shift in the composition of transaction money demand.

- As more consumers shift towards using QR codes, UPI payments, and contactless cards, the liquidity preferences for cash diminish, especially in urban areas.

- Technological advancements have also introduced innovations such as automatic recurring payments for bills, reducing the need for manual cash-based transactions.

- The growing adoption of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin in global economies also signals a shift in the future of money demand, although this has yet to have a significant impact in the Indian economy.

IV. Precautionary motive in Keynesian framework

Definition and significance of the precautionary motive

- Precautionary motive refers to the need to hold liquid money as a safeguard against unexpected events or financial emergencies.

- John Maynard Keynes highlighted the precautionary motive as a key reason individuals and businesses hold money, distinguishing it from transaction and speculative motives.

- The motive arises due to the uncertainty about future income and unforeseen expenditures that could impact individuals or businesses.

- Holding money for precautionary reasons ensures financial security in the face of unexpected occurrences, such as medical emergencies, economic downturns, or sudden business expenses.

Need for liquidity for unexpected events or emergencies

- Unforeseen circumstances: Individuals might encounter unexpected medical bills, sudden unemployment, or accidents that require immediate financial attention.

- Business disruptions: Firms may face sudden production halts, damage to equipment, or volatile market changes, necessitating the holding of cash reserves to manage these uncertainties.

- Natural disasters: Events such as floods, droughts, and pandemics can severely disrupt economic activities, increasing the demand for liquid assets to respond quickly.

- Having accessible liquid money allows both households and businesses to navigate these unforeseen crises without depending on borrowing or liquidating long-term investments.

Determinants of precautionary demand

- Income levels: Higher income earners may need less precautionary liquidity relative to their income, as they often have alternative sources of funds such as savings, credit, or investments. Lower-income groups, however, tend to hold more precautionary money due to limited access to financial services and safety nets.

- Uncertainty in the economic environment: In times of economic instability, such as during recessions, inflationary periods, or political instability, individuals and businesses prefer to hold more liquid assets to buffer against future financial risks.

- For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, precautionary demand for money surged as businesses and households anticipated further economic declines.

- Risk aversion: Individuals or firms with higher risk aversion are more likely to hold liquid money for precautionary reasons, as they may be less willing to take financial risks or engage in volatile investments.

- In India, small businesses in informal sectors are often highly risk-averse and tend to maintain higher levels of cash reserves due to the unpredictability of income and expenses.

Relation to the business cycle

- Economic fluctuations significantly influence precautionary demand for money.

- Boom periods: During economic booms, when income is rising and employment is stable, the need for precautionary money typically decreases, as individuals and businesses feel more secure in their financial position.

- Recession periods: Conversely, during recessions or periods of economic contraction, precautionary money demand increases due to heightened uncertainty about future income, job security, and business profitability.

- For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, precautionary demand for money sharply increased as global economic activity declined, and businesses faced disruptions in supply chains and demand.

- The business cycle thus plays a crucial role in shaping how much money is held for precautionary purposes. As economic confidence decreases, the demand for liquid assets increases.

Role of financial innovation

- New financial products have significantly influenced the landscape of precautionary money demand.

- Insurance systems: The availability of various insurance products, such as health insurance, life insurance, and property insurance, can reduce the need for individuals and businesses to hold precautionary liquid money. Insurance transfers the financial risk of unexpected events to the insurer, reducing the need to rely on cash reserves.

- For example, in India, schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), launched in 2018, provide health insurance coverage to lower-income groups, reducing their need to hold large amounts of cash for medical emergencies.

- Credit systems: Access to short-term credit or overdraft facilities offered by banks can also lower precautionary money demand, as individuals and firms can rely on borrowing to cover unexpected expenses rather than maintaining large liquid reserves.

- Digital credit platforms in India, like Paytm Postpaid and Bajaj Finserv, offer short-term financing options that reduce the need for precautionary cash.

- Liquidity management tools: Businesses increasingly use sophisticated liquidity management systems to optimize cash flows and reduce the need for precautionary reserves. Tools such as cash pooling, treasury management systems, and real-time liquidity monitoring have gained importance in the corporate world.

- Despite these innovations, precautionary motives for holding money remain relevant, particularly in regions or sectors with less developed financial systems or where access to financial products is limited.

V. Speculative motive and its unique role in money demand

Speculative motive

- Speculative motive refers to holding money in anticipation of future changes in interest rates and bond prices.

- Introduced by John Maynard Keynes in his liquidity preference theory, the speculative motive represents the need for liquidity to capitalize on expected changes in financial markets.

- Unlike the transaction or precautionary motives, the speculative motive is closely tied to individuals’ and firms’ expectations about future interest rate fluctuations and asset price movements.

- People hold money because they anticipate better returns in the future when interest rates rise or fall, influencing the price of bonds and other securities.

Expectation of changes in interest rates and bond prices

- The speculative demand for money increases when individuals expect interest rates to rise, leading to a fall in bond prices. In such a scenario, people prefer to hold cash rather than invest in bonds whose prices are expected to decline.

- Conversely, if people expect interest rates to fall, they will purchase bonds as bond prices are likely to increase, leading to a capital gain.

- This dynamic explains the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates: when interest rates rise, bond prices fall, and when interest rates fall, bond prices rise.

- The speculative motive is highly sensitive to market expectations regarding these fluctuations in interest rates.

Comparison with transaction and precautionary motives

- Motive:

- Speculative: To capitalize on anticipated changes in financial markets, particularly interest rates and bond prices.

- Transaction: To conduct daily financial activities, such as purchasing goods and services.

- Precautionary: To safeguard against unexpected future events, such as medical emergencies or sudden business expenses.

- Determinants:

- Speculative: Driven by market expectations, interest rate trends, and bond yield movements.

- Transaction: Primarily influenced by income levels and payment systems.

- Precautionary: Determined by risk aversion, income stability, and economic uncertainty.

- Economic impact:

- Speculative: Can cause large swings in money demand based on market psychology, leading to greater volatility in the financial system.

- Transaction: Affects the velocity of money circulation in the economy.

- Precautionary: Can lead to cash hoarding during times of economic uncertainty, reducing the availability of liquid capital for investments.

Money demand in the speculative context

- In the speculative context, money demand is influenced by interest rate expectations.

- When people believe interest rates will rise, they hold cash to avoid potential capital losses from declining bond prices.

- When interest rates are expected to fall, individuals are likely to invest in bonds or other assets that will increase in value.

- Bond yield movements are central to the speculative demand for money. As yields increase, bond prices fall, encouraging individuals to hold more liquid cash to avoid losses.

- Speculative money demand often fluctuates based on broader economic conditions, such as inflation expectations, central bank policies, and geopolitical events.

Keynes’ liquidity trap

- Liquidity trap occurs when interest rates are so low that individuals prefer to hold cash rather than invest, even if bond yields are expected to decline further.

- In such scenarios, the speculative demand for money becomes infinitely elastic, meaning that no matter how much the money supply increases, people will continue to hoard cash rather than invest in bonds.

- Keynes’ liquidity trap presents a significant challenge for monetary policy since lowering interest rates further has no effect on increasing investment or spending.

- Central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), find it difficult to stimulate the economy during a liquidity trap, as traditional interest rate cuts fail to reduce speculative money demand.

Speculative motive and asset bubbles

- The speculative motive can also lead to the formation of asset bubbles, driven by irrational speculation in financial markets.

- When investors expect continuous price increases in assets like real estate, stocks, or bonds, they may hold money to capitalize on price surges, further fueling the bubble.

- Irrational speculation can distort money demand by causing individuals to overvalue certain assets, leading to unsustainable investment patterns.

- For example, in India, speculative behavior in sectors such as real estate has contributed to asset price inflation in urban areas, where investors hold onto cash in anticipation of rising property values.

- When these bubbles burst, the demand for speculative money collapses, leading to market crashes and financial instability.

VI. The IS-LM model: Integration of money demand in Keynesian economics

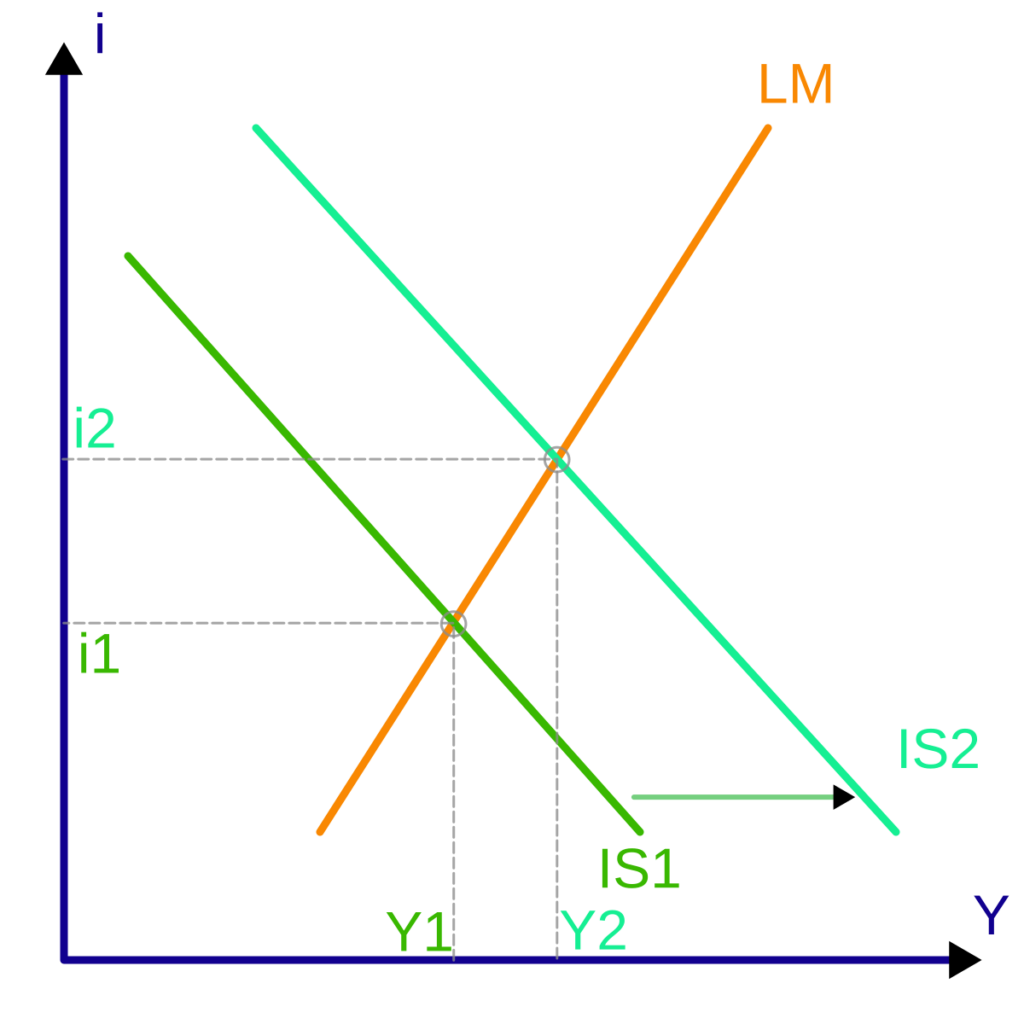

Overview of the IS-LM framework

- The IS-LM model is a macroeconomic tool that shows the interaction between the goods market and the money market, representing equilibrium in both.

- IS curve: Represents equilibrium in the goods market, where investment equals savings. It is downward sloping because as interest rates fall, investment increases, leading to higher output.

- The IS curve reflects the relationship between output (GDP) and interest rates in the goods market.

- LM curve: Represents equilibrium in the money market, where money demand equals money supply. It slopes upward because as income increases, the demand for money rises, leading to higher interest rates.

- The LM curve illustrates the relationship between output (GDP) and interest rates in the money market.

- The intersection of the IS and LM curves determines the equilibrium level of output (GDP) and the equilibrium interest rate in an economy.

Interaction between the goods market (IS curve) and money market (LM curve)

- The goods market and money market interact through interest rates, which affect both investment (in the goods market) and the demand for money (in the money market).

- When interest rates are low, investment in the goods market increases, shifting the IS curve to the right, leading to higher output.

- Higher income levels resulting from increased output raise the demand for money in the money market, shifting the LM curve upward.

- The IS-LM model shows how changes in monetary policy (affecting the LM curve) or fiscal policy (affecting the IS curve) impact interest rates and output levels.

Role of money demand in shaping the LM curve

- Money demand plays a crucial role in determining the slope and position of the LM curve. The LM curve shows the combinations of interest rates and output where the money market is in equilibrium.

- Interest rates influence money demand, as higher interest rates reduce the desire to hold liquid money, shifting the LM curve downward.

- Income levels also affect money demand, as higher income increases transaction demand for money, shifting the LM curve upward.

- Shifts in the LM curve occur when changes in money demand are caused by variations in interest rates or income.

- For example, when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) changes the money supply, it affects interest rates and shifts the LM curve.

Comparison between Classical and Keynesian views within the IS-LM model

- Static vs dynamic interpretations:

- Classical view: The economy is always in long-run equilibrium, meaning the IS-LM model focuses more on static equilibrium, where full employment is always achieved.

- Keynesian view: Emphasizes short-run fluctuations and the possibility of underemployment equilibrium, meaning the IS-LM model is used to analyze dynamic changes in output and employment, especially during economic downturns.

- Focus on money demand:

- Classical theory: Money is neutral in the long run, with the IS-LM model seen as less relevant for long-term growth analysis.

- Keynesian theory: Money demand is an active variable, shaping interest rates and output in both short-run and long-run analyses. The IS-LM model captures short-run demand fluctuations.

- Policy focus:

- Classical theory: Markets are self-correcting, and fiscal or monetary policy interventions are not necessary.

- Keynesian theory: Active fiscal and monetary policies are essential to manage demand, stabilize the economy, and prevent prolonged unemployment.

Implications for monetary policy

- The IS-LM model helps illustrate the effectiveness of monetary policy in managing the economy through control of the money supply and interest rates.

- Expansionary monetary policy: Increasing the money supply shifts the LM curve to the right, lowering interest rates and increasing investment, thereby raising output.

- Contractionary monetary policy: Decreasing the money supply shifts the LM curve to the left, raising interest rates, reducing investment, and lowering output.

- Shifts in money demand significantly impact the LM curve and, consequently, interest rates and output.

- For example, a sudden increase in money demand (due to increased economic activity or uncertainty) shifts the LM curve upward, leading to higher interest rates and potentially reducing investment.

- In the context of India, the RBI uses tools like the repo rate to influence the money supply and shift the LM curve, aiming to control inflation and stimulate economic growth.

- The IS-LM model also highlights the limitations of monetary policy during periods of liquidity traps, where lowering interest rates fails to stimulate investment or output growth, as seen during global financial crises.

- In such cases, fiscal policy becomes a more effective tool for boosting demand and output.

VII. Money demand and interest rate determination

Keynes’ theory on interest rate determination

- Keynes’ liquidity preference theory plays a central role in determining interest rates by focusing on the public’s preference for holding money over investing in bonds or other assets.

- According to Keynes, interest rates are the reward for parting with liquidity, meaning people demand compensation in the form of interest for giving up the ability to hold cash.

- Liquidity preference varies based on three motives: transaction, precautionary, and speculative motives, each contributing to the overall demand for money.

- The speculative motive is most significant in influencing interest rates, as individuals hold money when they expect bond prices to fall, causing interest rates to rise.

- The demand for money is thus a function of the interest rate (speculative motive) and income levels (transaction and precautionary motives).

Contrast with Classical theory: Loanable funds theory vs liquidity preference

- Loanable funds theory:

- Classical economists, such as Irving Fisher, believed interest rates were determined by the supply of and demand for loanable funds.

- In this theory, interest rates rise when savings are low and demand for investment is high, and they fall when savings are plentiful and investment demand is low.

- The theory assumes that savings are automatically turned into investment, with the interest rate acting as a balance between savings and investment.

- Liquidity preference theory:

- Keynes disagreed with the loanable funds theory, arguing that interest rates are not determined by savings and investment but by liquidity preference.

- In the liquidity preference model, individuals decide how much money to hold based on their expectations of future interest rates and their motives for holding money.

- This theory emphasizes the role of central banks in influencing money supply to control interest rates, rather than relying on the market to balance savings and investment.

Interaction between money supply and demand

- Central bank policies play a crucial role in adjusting the money supply, which directly affects interest rates.

- For instance, when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) increases the money supply through open market operations or by lowering the repo rate, more money becomes available, leading to lower interest rates.

- Conversely, reducing the money supply by raising the repo rate or selling government securities raises interest rates.

- The money demand curve is downward-sloping, meaning that as interest rates rise, individuals demand less money for speculative purposes, preferring to invest in bonds or other assets that offer higher returns.

- When interest rates fall, the demand for money increases because the opportunity cost of holding cash is lower.

Interest rate elasticity of money demand

- The elasticity of money demand refers to how responsive the demand for money is to changes in interest rates.

- High elasticity: In situations where money demand is highly elastic, small changes in interest rates lead to large shifts in money holding behavior. This is common during periods of economic uncertainty, when people are more sensitive to interest rate changes.

- Low elasticity: In contrast, when money demand is inelastic, even large changes in interest rates have minimal impact on how much money people choose to hold.

- Implications for monetary policy:

- When money demand is highly elastic, central banks have more control over the economy through interest rate adjustments. For example, lowering interest rates can quickly boost investment and spending.

- However, when money demand is inelastic, monetary policy becomes less effective because changes in interest rates have little impact on money demand or economic activity. This is often seen during liquidity traps.

Role of expectations in interest rate determination

- Expectations play a critical role in determining interest rates, as both psychological and economic factors shape market behavior.

- Psychological factors: Investors’ expectations about future interest rates and bond prices drive their decisions to hold or invest money.

- If investors expect interest rates to rise, they will hold onto money, leading to higher interest rates in the present.

- If investors expect rates to fall, they will invest in bonds, lowering current interest rates.

- Economic factors: These include inflation expectations, central bank policies, and overall economic stability.

- When inflation is expected to rise, interest rates generally increase to compensate for the loss of purchasing power.

- Central bank signals regarding future policy actions also influence market expectations. For example, if the RBI signals it will raise interest rates in the future, current interest rates may rise in anticipation.

- Market psychology can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies in interest rate determination. For example, if enough investors believe interest rates will rise, their actions (holding money) will cause rates to increase, regardless of the central bank’s intentions.

VIII. Critiques of Keynesian money demand theory

Criticism from monetarist perspective

- Milton Friedman led the Monetarist critique against Keynesian money demand theory.

- Friedman’s reinterpretation of money demand focused on the permanent income hypothesis. He argued that people’s demand for money is determined by their long-term average income rather than their current income, challenging Keynes’ short-term focus on income and interest rates.

- He also emphasized the quantity theory of money, which suggests a direct relationship between the money supply and price levels, rejecting Keynes’ liquidity preference theory that focuses on interest rates as the primary factor.

- Monetarists believed that controlling the money supply was more effective for managing inflation and economic stability than manipulating interest rates, as advocated by Keynes.

- Criticism of Keynes’ liquidity preference theory: Monetarists argued that the focus on speculative demand for money underestimated the stability and predictability of money demand over time.

Rational expectations school

- The rational expectations school, developed by economists like Robert Lucas, critiqued Keynesian theories for their reliance on short-run economic fluctuations and reactive policies.

- This school emphasized the importance of forward-looking behavior in economic decision-making. People and firms are assumed to form expectations about the future based on all available information, making them less likely to be influenced by short-term policy changes.

- According to this critique, Keynesian policies—such as adjusting the money supply or interest rates to influence demand—are often ineffective because people will anticipate and counteract these policies.

- Rational expectations theorists argued that government intervention through monetary policy could lead to policy ineffectiveness, as people would adjust their behavior in anticipation of these changes, neutralizing their intended effects.

New Keynesian critique

- The New Keynesian approach updated Keynes’ original ideas by incorporating price stickiness and wage rigidity into models of money demand and economic fluctuations.

- Price stickiness refers to the idea that prices do not adjust immediately to changes in supply and demand, meaning that short-term economic shocks can have prolonged effects.

- Wage rigidity suggests that wages do not easily fall even in the face of unemployment, which can lead to sustained periods of underemployment.

- These factors lead to incomplete adjustments in the market, supporting the idea that active fiscal and monetary policies are necessary to stabilize the economy during periods of disequilibrium.

- New Keynesians expanded on Keynes’ liquidity preference theory by focusing on nominal rigidities and their impact on how money demand interacts with other macroeconomic variables.

Comparison of Keynesian and monetarist views

- Role of expectations:

- Keynesian: Short-term expectations about interest rates and income drive money demand.

- Monetarist: Long-term income expectations, driven by the permanent income hypothesis, shape money demand.

- Central bank policy:

- Keynesian: Central banks should manage interest rates to influence investment and consumption.

- Monetarist: Central banks should focus on controlling the money supply to ensure price stability.

- Money demand elasticity:

- Keynesian: Money demand is sensitive to changes in interest rates, particularly under speculative motives.

- Monetarist: Money demand is more stable and predictable, with less reliance on interest rate movements.

Post-Keynesian interpretations

- Post-Keynesian economists argue that money demand is driven by endogenous factors, meaning the supply of money is determined within the economy rather than by the central bank.

- They emphasize the importance of the financial instability hypothesis, developed by Hyman Minsky, which highlights how financial markets can become inherently unstable due to speculative bubbles and crises.

- According to this view, liquidity preference can change dramatically during times of financial instability, as seen in the 2008 global financial crisis, when demand for money surged as a response to collapsing asset prices.

- Post-Keynesians also critique traditional monetarist and Keynesian views for underestimating the role of credit creation and the complex interactions between the banking sector and money supply.

IX. Empirical evidence and application of Keynesian money demand theory

Studies supporting liquidity preference theory

- Empirical studies have supported Keynes’ liquidity preference theory, showing that individuals hold money based on interest rate expectations and future economic conditions.

- Historical data:

- During the Great Depression (1930s), Keynesian theory explained why low interest rates did not stimulate investment, as people preferred to hold onto liquid cash due to economic uncertainty.

- Contemporary data:

- Modern studies continue to confirm the relationship between money demand and interest rate levels. In periods of low interest rates, money demand rises as speculative motives for holding cash increase.

- For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, empirical data showed a significant increase in liquidity preference as financial institutions and individuals hoarded cash instead of investing in assets with falling returns.

Comparison of empirical studies: Keynesian vs monetarist interpretations

- Keynesian interpretation:

- Keynesian studies suggest that money demand is highly sensitive to interest rate changes and speculative motives.

- Empirical data from periods of economic crisis (e.g., 2008 crisis) demonstrate increased demand for liquid money due to rising uncertainty, supporting Keynes’ liquidity preference theory.

- Monetarist interpretation:

- Monetarists, led by Milton Friedman, argue that money demand is more stable and tied to long-term income rather than short-term interest rate fluctuations.

- Empirical studies focusing on periods of economic stability show that money demand is relatively predictable, as the quantity theory of money suggests.

- Key contrasts:

- Keynesian studies emphasize the role of psychological factors (fear of future interest rate changes), while monetarist studies focus on the permanent income hypothesis and long-term money demand stability.

Keynesian money demand in modern economies

- Developed economies:

- In countries like the United States and Japan, Keynesian money demand theory is applicable, particularly during economic downturns. In these nations, low interest rates often lead to increased money demand, as individuals and businesses prefer to hold cash in uncertain times.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, developed economies experienced liquidity traps, where central banks lowered interest rates, but investment did not rise due to increased liquidity preference.

- Developing economies:

- In countries like India, liquidity preference is influenced by economic uncertainty, but the demand for cash is also shaped by factors such as limited access to financial services and a high reliance on cash transactions.

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has used Keynesian principles in managing monetary policy, particularly in controlling liquidity through changes in the repo rate to influence interest rates and encourage investment.

Challenges in empirical testing

- Measuring speculative demand:

- A major challenge in empirical testing of Keynesian money demand theory is accurately measuring speculative demand. Speculative motives are influenced by individuals’ expectations about future interest rates, which are difficult to quantify.

- Empirical studies often rely on proxies, such as bond yield spreads, but these do not fully capture the psychological factors driving liquidity preference.

- Changing financial landscapes:

- The rapid evolution of financial markets and instruments poses challenges for testing Keynesian theory. With the advent of digital banking, cryptocurrencies, and real-time payment systems, the traditional concept of liquidity preference has evolved.

- These innovations have changed how individuals and businesses hold money, making it harder to apply Keynes’ original models in modern economies.

Role of financial innovation

- New financial products have transformed the landscape of money demand and liquidity preference.

- Digital payment systems:

- In countries like India, the rise of Unified Payments Interface (UPI) (launched in 2016) has reduced the need for physical cash, as individuals and businesses can make real-time transactions with ease.

- This shift in payment behavior affects the demand for liquid money and speculative motives, as cashless transactions reduce the need to hold large cash reserves.

- Financial derivatives:

- The growth of financial derivatives and hedging tools allows investors to manage risk without holding liquid cash. This reduces the speculative demand for money in advanced economies.

- Cryptocurrencies:

- The increasing use of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin has further impacted money demand. Digital currencies offer an alternative to traditional cash, influencing liquidity preference, especially in countries where trust in national currencies is low.

- Challenges posed by innovation:

- While financial innovation has reduced traditional liquidity preference in some areas, it has also introduced new risks. For example, volatility in cryptocurrency markets has created speculative demand for digital assets, echoing Keynes’ original theory of liquidity preference in a modern context.

X. Modern relevance of Keynesian money demand

Evolution of the liquidity preference theory

- Liquidity preference theory has evolved significantly since John Maynard Keynes first introduced it in the 1930s.

- Changes in economic conditions:

- The Great Depression heavily influenced Keynes’ original theory, emphasizing the need to hold liquid money during economic downturns.

- Post-World War II, as economies stabilized, liquidity preference shifted due to better financial infrastructure and higher economic growth.

- Changes in financial systems:

- The rise of modern banking systems, digital payments, and global financial markets transformed how money is held and transferred.

- Keynes’ original theory has been adapted to account for technological advancements such as online banking and mobile payments.

Application in contemporary macroeconomic policy

- Liquidity preference continues to play a critical role in shaping interest rates and monetary policy in the 21st century.

- Central banks like the Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) use liquidity preference as a tool to manage inflation and control money supply.

- Monetary policy tools:

- In India, the repo rate is frequently adjusted by the RBI to manage liquidity in the market and control inflation.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, liquidity preference surged, leading central banks globally to implement quantitative easing (QE) and cut interest rates to near zero.

- The role of speculative motives remains significant in determining interest rates, as seen during periods of economic uncertainty when individuals and institutions prefer holding cash instead of investing in volatile markets.

Comparison with other modern theories

- Relevance in an age of low interest rates:

- In an era of near-zero interest rates, particularly in advanced economies like Japan and the Eurozone, Keynes’ liquidity preference theory remains relevant as it explains why individuals and businesses may hoard money even when interest rates are low.

- Quantitative easing (QE):

- QE, implemented by the Federal Reserve (2008) and other central banks, aimed to inject liquidity into the economy by purchasing government bonds, increasing the money supply. This aligns with Keynes’ notion that increasing liquidity can stimulate investment during downturns.

- Digital currencies:

- The rise of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum has introduced new complexities in liquidity preference, as individuals may now prefer holding digital assets instead of cash, challenging traditional assumptions about money demand.

- Other modern theories:

- The New Monetarist school, which focuses on the role of money and credit, contrasts with Keynesian liquidity preference by placing more emphasis on the stability of money demand rather than on short-term interest rate fluctuations.

Implications for future research

- The modern technological landscape calls for refinements in the theory of money demand, particularly in light of digital banking, mobile payments, and cryptocurrencies.

- Directions for refining liquidity preference:

- The rise of fintech and the global shift towards cashless economies necessitate updates to Keynesian theory, particularly in how digital payment systems affect the need for liquid cash.

- Empirical studies are required to explore how digital currencies impact liquidity preference, especially in developing economies like India where mobile banking and UPI have significantly reduced cash demand.

- Financial inclusion:

- Future research should focus on the implications of liquidity preference in economies with rising financial inclusion, particularly in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where mobile banking is transforming money demand patterns.

- Climate risk and economic instability:

- Increasing concerns about climate change and its economic impacts may alter how businesses and individuals approach liquidity, creating new speculative and precautionary motives in response to potential environmental disruptions.

- Analyze how Keynes’ concept of liquidity preference reshapes the traditional understanding of money demand, focusing on its implications for interest rate determination and central bank policies. (250 words)

- Compare Keynes’ theory of money demand with the Monetarist critique, highlighting the differences in their approach to expectations, money demand elasticity, and the role of monetary policy. (250 words)

- Examine the relevance of Keynes’ speculative motive for money demand in modern economies, considering the impact of financial innovation and changing interest rate environments. (250 words)

Responses