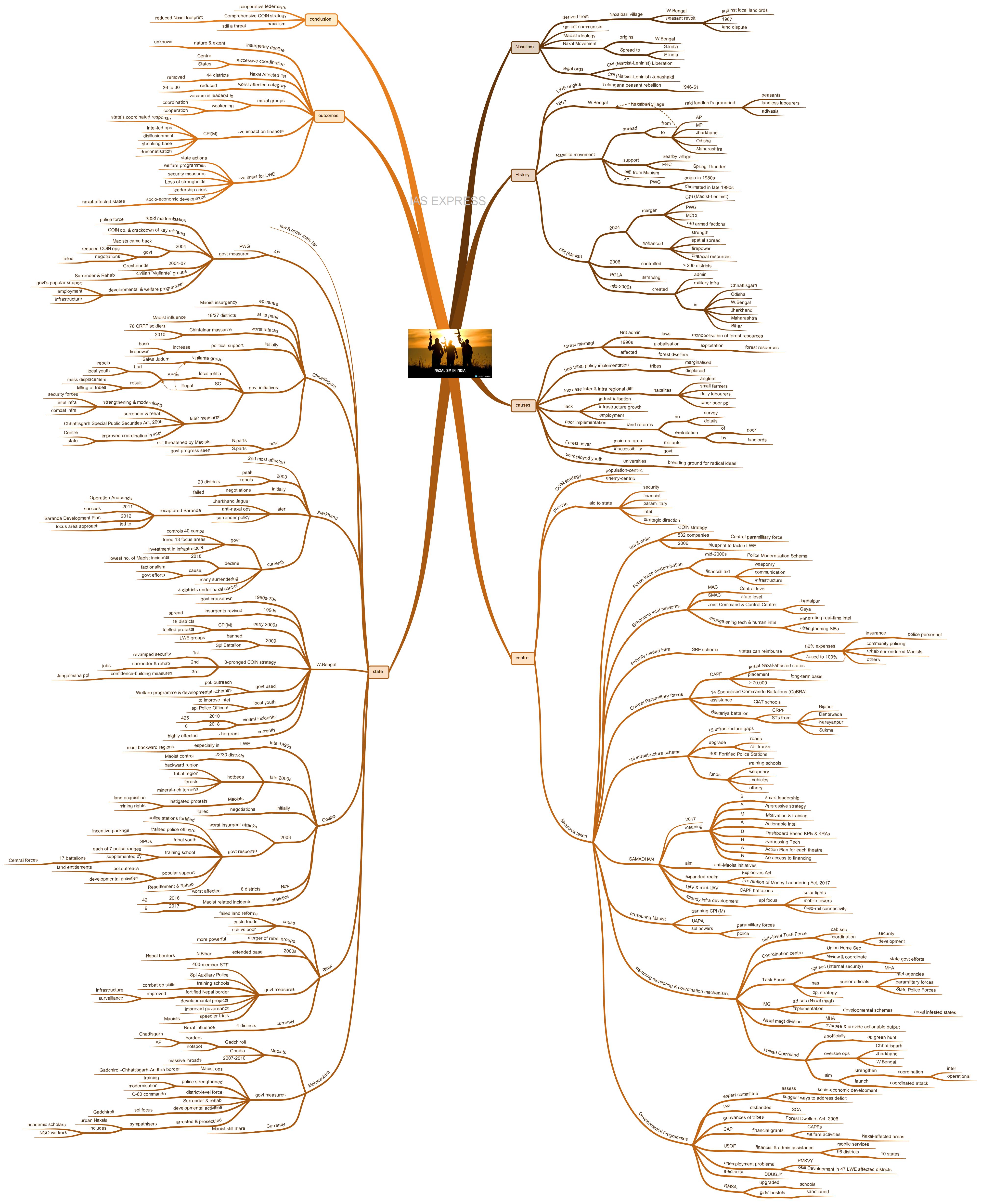

Naxalism in India: Causes, Government Response & its Outcomes

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 80+ questions reflected

Left-wing extremism has been a major threat to India since the 1960s. Many of these militant groups, for many years, had held the mineral-rich lands under their influence. Both the states and Central government, through a series of measures, had significantly improved their presence in the Naxal-infested regions. Currently, these militant groups are only operating in a few isolated regions. However, they still pose a substantial threat to India’s national security.

What is Naxalism?

- The term Naxalism derives the name of the Naxalbari village in West Bengal where a peasant revolt took place against local landlords who had beaten up a peasant over a land dispute in 1967.

- The Naxalites are considered to be the far-left communists who support Mao Zedong’s political ideology.

- Initially, the Naxalite movement originated in West Bengal and had later moved to the less developed rural areas in Southern and Eastern India, including in the states of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana.

- Some Naxalite groups have legal organisations as representatives in the parliament like the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation and the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Janashakti.

- As of April 2018, the states where Naxalites are most visible are Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Odisha and Telangana.

How did it come to be?

- Maoist movement in India is among the longest and most deadly insurgencies that originated in India.

- While the origins of Left Wing Extremism (LWE) in India goes back to Telangana peasant rebellion (1946-51), the movement was at its peak in 1967, when the peasants, landless labourers, and Adivasis raided the granaries of a landlord in the Naxalbari village in West Bengal.

- This rebellion was suppressed by the police force, which consequently led to the Naxalite movement under the leadership of Charu Majumdar and his close associates, Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal.

- These rebels not only were assisted by the people from nearby villages but also from the People’s Republic of China. The Chinese Media had called this movement the “Spring Thunder”.

- The movement initially took inspiration from China’s founding father, Mao Zedong, but had later become radically different from Maoism.

- In the following decades, the movement had later spread to other regions in the country.

- Most notably, in the 1980s, Andhra Pradesh saw the formation of People’s War Group (PWG) under the leadership of Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, which fought for the cause of peasants and the landless through a series of violent attacks, assassinations, and the bombing of Andhra Pradesh’s landlords, upper-caste leaders, and politicians.

- In the late 1990s, Andhra Pradesh police had decimated the PWG. However, this did not end the insurgency problem in India as it had spread across the nearby Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and parts of Maharashtra.

- In 2004, the merging of the Communist Party of India (Maoist-Leninist), PWG, Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI) and 40 other armed factions under the Communist Party of India (Maoist) had turned the tide in favour of the insurgents.

- Before this, the Maoists were relatively a minor force, separately operating within four states – Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Andhra Pradesh. They were so fragmented that there were even instances of conflicts and killing between these groups.

- The 2004 merger of the two major Maoist factions had led to the strategic breakthrough, allowing the insurgents to enhance their strength, spatial spread, and firepower.

- This movement had eventually spread across such vast geography that it had surpassed all other insurgent groups in India, including in the Jammu and Kashmir and the North East.

- In 2006, they controlled more than 200 districts across the country.

- The insurgents had rapidly enhanced their firepower, arms, ammunition, and cadre with improved expertise.

- In a short span of time, the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PGLA), the armed wing of the CPI (Maoist) had nurtured 20,000 regular cadres who were armed with automatic weapons, shoulder rocket launchers, mines, and other explosive devices, etc.

- They are experts at making and deploying high-end bombs and some reports even claim that they have set up manufacturing centres for weapons like rocket launchers.

- By the mid-2000s, the Maoists had managed to create full-fledged administrative and military infrastructures in the states of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Bihar, and West Bengal.

- The improvement in the financial resources had significantly enhanced their ability to buy weapons, attract recruits and modernise communication warfare systems including the use of Information and communication technology.

- The worst of the recent attacks by these groups include the Chintalnar massacre of 76 soldiers in Chhattisgarh’s Dantewada district in April 2010 and the assassination of top leaders of the Congress Party in Chattisgarh’s Jerram Ghati area in Sukma district in May 2013.

What are the causes of Naxalism?

- Forest mismanagement was one of the main causes of the spread of Naxalism. It originated during the time of British administration when new laws were passed to ensure the monopolisation of the forest resources. Following the globalisation in the 1990s, the situation worsened when the government increased the exploitation of the forest resources. This led the traditional forest dwellers to fight for their aspirations against the government through violence.

- Haphazard tribal policy implementation, marginalisation, and displacement of the tribal communities worsened the situation of Naxalism.

- The increase in the interregional and intraregional differences and inequalities led to people choosing Naxalism. Naxal-groups mostly consist of the poor and the deprived like the anglers, small farmers, daily labourers, etc. The government policies have failed to address this issue.

- Lack of industrialisation, poor infrastructure growth and unemployment in rural areas led to disparity among the people living in these areas. This has led to an anti-government mindset among the locals in the isolated villages.

- The poor implementation of the land reforms has not yielded the necessary results. India’s agrarian set up is characterised by the absence of proper surveys and other details. Due to this reason, it has greatly damaged the rural economy and anti-government sentiments were high among those who were deprived and exploited by the local landowners.

- Forest cover in India is the main area of operation for these groups. The government is facing difficulties while dealing with the insurgents due to the lack of accessibility to these areas.

- The unemployed youth in India is one of the major supporters of the Naxalism movement. This group mostly consists of medical and engineering graduates. The universities have become one of the major breeding grounds for radical ideologies.

How did the government respond to it?

State governments:

- States’ response to the Maoist insurgency has evolved over the years, influenced by the intensity of the threat and political decisions at the state and centre.

- Since the law and order come under the state list, the critical counterinsurgency initiatives come under the jurisdiction of the State governments.

- The Centre is involved in supporting these efforts through joint strategies, providing resources, intelligence, and coordination when necessary.

Andhra Pradesh:

The undivided Andhra Pradesh saw the rise of PWG in the early 1990s. The state government’s response to this insurgent group includes:

- The rapid modernisation of the police force

- Launch of full-scale counterinsurgency operations and massive crackdown of key Maoist leaders in the state

- After the short-term strategic defensive stage, the Maoist group scaled back on its operations in 2004.

- In 2004, the government reduced its counterinsurgency operations and engaged in negotiations with the insurgent leaders.

- The failure of talks led to the relaunch of the offensive.

- The elite combat force, the Greyhounds, was used between 2004 and 2007 to successfully crack down the top Maoist leaders.

- The state had also quashed mass organisation activities by using civilian “vigilante” groups that had been carefully encouraged through the attractive Surrender and Rehabilitation package.

- The government also gained public trust and reduced the insurgent groups’ popularity through developmental projects and welfare programmes to all, including the tribal communities.

- The AP government had also provided healthcare, education, clean drinking water, pucca houses with sanitation facilities, electricity, roads, etc to all villages within three years while also providing Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme.

- These measures had made the state government more popular than that of the left-wing extremist groups operating in the area.

- Thus, through the combination of police action and developmental programmes, the state government has successfully addressed the problem of left-wing extremism in the state.

Chhattisgarh:

- Today, Chhattisgarh is the epicentre of Maoist insurgency in India.

- At its peak, these groups had influenced over 18 districts out of the total 27.

- This state is the home for the so-called Red Corridor and these regions are believed to be intensively mined by the Maoists.

- The worst of the attacks in this area include the Chintalnar massacre of 76 CRPF soldiers in 2010 and the assassination of the top political leaders in 2013.

- In the initial years of the creation of Chhattisgarh as a separate state, it saw the political support to the insurgent groups leading to them expanding their base and firepower.

- Later, the government took various steps including the nurturing and strengthening of the vigilante group, popularly known as Salwa Judum and creating a local militia called Special Police Officers (SPOs) comprising of rebels and local youth.

- However, this strategy resulted in mass displacement and killing of the tribal communities who were caught between the two factions.

- In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the vigilante group was illegal and ordered the state government to disband it.

- After this incident, the state government focused on strengthening and modernising the security forces, intelligence, and combat infrastructure, particularly establishing an anti-insurgency training school for the police.

- It had also adopted a Surrender and Rehabilitation policy and had passed the Chhattisgarh Special Public Securities Act, 2006, which expanded the purview of the “unlawful” activities to verbal or oral communications.

- The roads and communication networks were also improved in the challenging terrains and the government had also launched the pioneering socio-economic schemes for the poor.

- While Maoist-led violence remains a major concern in the northern parts of Chhattisgarh, progress has been made in restricting Maoists in the state’s southern districts.

- Improvement in road connectivity, enhancement of combat capability of the local police through modernisation and fortification of the police stations and improved coordination between the Centre and the state in intelligence and paramilitary force has significantly reduced the Maoist threat.

Jharkhand:

- Jharkhand is the second most affected by the LWE after Chhattisgarh.

- At their peak in 2000, the rebels held about 20 districts across the state.

- Initially, the state government attempted negotiations with these groups. Its failure led to the formation of special force (Jharkhand Jaguar modelled after the Greyhounds of AP) and initiation of anti-Naxal operations.

- The state government had also framed a unique surrender policy for the Naxalites.

- The most crucial operation for Jharkhand’s state forces was the ambitious plan to recapture the forested region of Saranda, which had been a Maoist stronghold since the early 2000s.

- Together with central forces, the state launched Operation Anaconda to counter Maoists operating in Saranda.

- After its success in 2011, the Centre had immediately framed the Saranda Development Plan in 2012.

- The success of the Saranda strategy prompted the state government to expand the focus area approach to free more of such locations and undertake developmental projects.

- The government has so far taken control over 40 camps and freed 13 focus areas from Maoist influence.

- Currently, the government is heavily investing in the construction of infrastructure projects like roads, bridges, schools, etc.

- The past years saw a decline in the Maoist incidents in this state.

- The year 2018 had the lowest number of Maoist incidents.

- Furthermore, a large number of rebels are surrendering – as many as 108 in 2018 alone.

- While at their strongest, the Naxalites in Jharkhand held 13 districts under their control. Now, only hold four districts.

- The success is attributed to the state government’s efforts and factionalism within the Maoists’ ranks.

- However, this does not mean the LWE is completely eliminated. There still exist active rebel hotspots across the state.

West Bengal:

- West Bengal, the birthplace of the 1967 Naxalite uprisings, had witnessed an unprecedented rise in Maoist insurgency a decade ago.

- The state government had taken a series of military actions in the late 1960s and the early 1970s to deal with these insurgent groups.

- Yet, in the late 1990s, the Maoists had managed to revive their hold and had spread across the state.

- By the early 2000s, the CPI-Maoists had control over 18 districts and played a crucial role in fuelling agitations in many of them.

- Initially, the state government’s response was inconsistent and reluctant to cooperate with the Centre and other states.

- However, due to the intensity of the violence, the state government indulged in serious counterinsurgency campaigns.

- In 2009, the state government had banned various left-wing extremist groups and had created Special Battalion to deal with the insurgency in the state.

- Later, the government adopted a 3-pronged counterinsurgency strategy.

- First, the government refurbished the security strategy by setting up an elite police team to pursue the rebel leaders.

- Second, the government offered to surrender and rehabilitation package to the rebels, promising jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities to those who surrendered.

- The third was the formation of comprehensive confidence-building measures with the people living in the Maoist-infested Jangalmaha region.

- The government had combined two components to quash the left extremists:

- Political outreach

- Welfare programme and developmental schemes.

- To strengthen the intelligence and police combing operation, the government had actively incentivised the local youth to serve as informants and formed the so-called Special Police Officers (similar to vigilante groups in other Naxal-affected states.

- The political outreach and welfare programmes had greatly strengthened the government’s presence in the neglected regions like the tribal villages.

- From a peak of 425 Maoist-related violent incidents in 2010, the number had come down to zero by the end of 2018.

- The government had even successfully negotiated with several rebels, including top leaders to make them surrender to the police.

- This state has only one district (Jhargram), which remains under the category of “highly affected” by the insurgency.

Odisha:

- In the late 1990s, Odisha saw a rapid spurt in the LWE, especially in the most backward regions consisting of large tribal populations.

- At one point in the late 2000s, the Maoists influenced 22 of the 30 districts of Odisha.

- The hotspots of the Maoist activities were the most backward and forested, mineral-rich districts which had a large number of tribal population.

- The intensity of the attacks by the groups was so bad that a large number of people died, properties were destroyed, government systems were paralysed and the economic activities were disrupted.

- The insurgents had also fuelled protests against several projects on the issues of land acquisition and mining rights.

- Initially, the state government had negotiated and even allowed a rally in the capital. However, this did not yield the intended results.

- 2008 saw the worst of the insurgent attacks in the region, leading to the government’s rapid measures to address the issue.

- The government had immediately fortified the police stations, provided training to the police officers and announced, the necessary incentive package to the police personnel involved in the anti-Maoist operations.

- It had also trained thousands of tribal youth from the insurgency-affected areas to recruit them as Special Police Officers (SPOs).

- The state also opened a training school in each of the 7 police ranges, supplemented by 17 battalions of Central forces stationed in key Naxal-affected districts.

- Apart from law and order measures, developmental activities and political outreach were also undertaken to gain popular support in the insurgent-affected areas.

- This included land entitlements to the tribal communities across several Naxal-infested districts.

- Odisha also came up with the Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy to address core issues related to land acquisition and displacement.

- Over time, the state government had achieved progress in managing the LWE in the mineral-rich regions though there are occasional attacks from these factions.

- As per the statistics, the Maoist related incidents has declined from 42 in 2016 to 9 in 2017.

- Between 2015 and 2016, more than 1,000 Maoists have surrendered to the police.

- Currently, only 8 districts remain “worst affected”.

Bihar:

- Bihar is among the few states where the LWE took deep root in the 1970s.

- At their peak, the Maoists enjoyed widespread popularity among the poor and the marginalised.

- The cause for this includes the failed land reforms, caste feuds and the rich suppressing the poor.

- These rebel groups had merged, leading them to become more powerful.

- In the 2000s, the rebels had extended their base to North Bihar that has borders with Nepal.

- In 2005, the state government took steps to restore law and order.

- There was an improvement in governance and the government undertook various socio-economic and developmental initiatives.

- The jailbreak and the release of 394 convicts by the insurgents had led to the state government’s greater emphasis on the anti-Naxal campaign.

- The government had set up 400-member Special Task Force along with Special Auxiliary Police for counterinsurgency operations.

- It had also established specialised counterinsurgency training schools to improve the combat operation skills of the security personnel.

- Additionally, it had fortified the long and porous Nepal border through improved infrastructure and surveillance to address other illegal activities like fake currency, drug trafficking, etc.

- The state government had revamped the surrender and rehabilitation policy to make it more attractive for the insurgents.

- The measures that saw greater results were the developmental projects and improved governance.

- These efforts were branded as “effective politics”.

- To improve law and order and gain the public’s trust, the government had ensured the speedier trials for the Maoists.

- These measures showed a significant improvement in the anti-Naxal campaigns.

- While the state saw as many as 22 of the 38 districts under the Naxal influence, it has currently come down to four.

Maharashtra:

- Maoists currently have a foothold, in varying degrees, in Maharashtra’s districts of Gadchiroli and Gondia, which have areas contiguous with the Dandakaranya region of Chhattisgarh.

- Gadchiroli has borders with both Chattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh, leading to it becoming the hotspot for Maoist activities in the state.

- In 2007-2010, the Maoists had made massive inroads into this strategic belt and in recent times, had launched daring assaults against the security forces.

- Compared to other Maoist-infested states, Maharashtra responded rather seriously with a combination of developmental and security components.

- The following measures were taken by the government:

- A major offensive against the Maoists in the Gadchiroli-Chhattisgarh-Andhra border.

- Police machinery was strengthened in Naxal-infested areas through training and modernisation of equipment.

- Created a district-level force called C-60 commando,

- Surrender and Rehabilitation policy led to the surrender of more than 500 rebels, including some prominent leaders in the past 12 years.

- Special focus was given in the developmental activities, especially in Gadchiroli,

- Authorities have arrested and prosecuted individuals who were identified as Maoist “sympathisers”, giving them a pejorative name, “urban Naxals”. These individuals include academic scholars and NGO workers.

- The state police along with the Central paramilitary forces have successfully killed numerous rebels and arresting hundreds of them.

- Currently, the Maoists are still visible in the tribal districts, particularly in Gadchiroli. The Naxals are still able to launch attacks in their stronghold.

Central government:

The previous UPA government at the Centre had laid the foundation for India’s Counter-Insurgency (COIN) strategy and the current government has accelerated the paces and effectiveness of the COIN strategy. These strategies have integrated the population-centric and enemy-centric approaches, combining law and order mechanisms and development instruments. Centre has largely led the COIN efforts from behind by providing resources like security and financial support, paramilitary, intelligence, and strategic direction. Overall, the COIN involves a mixture of population-centric and enemy-centric approach to deal with insurgents in India with the aim to complement state initiatives. It involves the following:

Law and order approach:

- It plays a key role in the Centre’s counterinsurgency strategy.

- It is seen in the deployment of about 532 companies of the central paramilitary forces in the affected states.

- In 2006, for the first time, the government had issued a security blueprint to tackle Maoist extremism.

Police force modernisation:

- The government had realised that the Maoist insurgents were highly successful due to the lack of strong and effective policing.

- To improve the quality of policing, in the mid-2000s, the Centre had implemented a Police Modernization Scheme.

- Centre had also provided enormous financial aid to the states for the modernisation and up-gradation of police forces’ weaponry, communication, and infrastructure.

- It was recently found that the improvement in police modernisation and intelligence gathering had brought in success for the police’s anti-Maoists campaigns.

Enhancing intelligence networks:

- Poor intelligence infrastructure at the state level was a major nuisance to the counterinsurgency campaign.

- The Centre, in consultation with states, took steps to enhance and upgrade the capabilities of the intelligence agencies. This includes:

- Round-the-clock intelligence sharing through Multi-Agency Centre (MAC) at the Central level and through State Multi-Agency Centre (SMAC) at the state level.

- Setting up of the Joint Command and Control Centre at Maoist hotbeds like Jagdalpur and Gaya,

- Strengthening of technical and human intelligence through cooperation among the security forces, district police, and intelligence agencies

- providing thrust on the generation of real-time intelligence and creation/strengthening of the State Intelligence Bureaus (SIBs) in LWE-affected states for which the Central assistance is provided through the Special Infrastructure Scheme.

Assisting States in security-related infrastructure:

- The Centre had launched the Security Related Expenditure (SRE) scheme to allow the states to reimburse 50% of their expenses on provisions like insurance scheme for police personnel, community policing, rehabilitation for the surrendered Maoists and other security-related items not covered under the Police Modernisation Scheme.

- Recently, the current government has raised the SRE reimbursement to up to 100%.

- Now it also allows the advance release of the funds to the Naxal-affected states.

Deploying Central Paramilitary forces:

- The centre had created the Central Armed Police Force (CAPF) to assist the Naxal-affected states.

- It has extended the placement of CAPFs on a long-term basis. This is similar to its approach in the Northeast and Kashmir.

- Currently, more than 70,000 CAPFs are deployed in the Maoist-affected states.

- Also, the Centre had assisted the states to raise 14 Specialised Commando Battalions (CoBRA) that are well equipped and trained in guerrilla and jungle warfare techniques.

- Furthermore, the Centre had assisted in creating a number of Counter Insurgency and Anti-Terrorist (CIAT) schools for the long-term sustainability of the counter-offensives.

- The Centre had also announced the setting up of a Bastariya battalion in CRPF from Scheduled Tribe candidates belonging to four districts – Bijapur, Dantewada, Narayanpur and Sukma of Chhattisgarh.

Special Infrastructure Scheme

- This is to fill the infrastructure gaps that are not covered under the existing schemes.

- It includes up-gradation of roads and rail tracks to improve the mobility of the security personnel and providing secure camping grounds and helipads at a strategic location in remote areas.

- Under this scheme, about 400 Fortified Police Stations were opened in Maoist-affected states.

- Additionally, the Centre also provides funds for the creation of training schools, weaponry, vehicles and other requirements for the LWE-affected states.

SAMADHAN:

- Launched in 2017, it stands for S – smart leadership, A – Aggressive strategy, M – Motivation and training, A – Actionable intelligence, D – Dashboard Based KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas), H – Harnessing Technology, A – Action Plan for each theatre and N – No access to financing.

- Its aim is to enhance the government’s anti-Maoist initiatives, even the basic components of the counterinsurgency campaign.

- The Centre has expanded the realm of the existing provisions under the Explosives Act and Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2017 to monitor the transportation of the explosive substance and hinder the flow of finances of the insurgents.

- UAV and mini-UAV were introduced for each of the CAPF battalions deployed in the Maoist hotbeds.

- Speedy infrastructure development with special focus on solar lights, mobile towers and road-rail connectivity in inaccessible areas of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand.

The banning of CPI (Maoist) and enactment of the UAPA Act, 1967

- The nationwide ban on CPI (Maoist) and the enactment of UAPA ensured pressure on Maoists.

- Also, the government had provided autonomy and sweeping powers to police and paramilitary forces to take legal action against the banned organisations and their activities.

Enhancement of monitoring and coordination mechanisms:

- Establishment of high-level Task Force under the Cabinet Secretary for promotion of coordination across a range of security and developmental measures.

- Coordination Centre, chaired by the Union Home Secretary, was established to review and coordinate efforts of concerned state governments in close consultation with Chief Secretaries and Director Generals of Police of respective states.

- Task Force, headed by a Special Secretary (Internal Security) in the Ministry of Home Affairs with senior officers from intelligence agencies, paramilitary forces and State Police Forces was set up to deliberate on operational strategies.

- Inter-Ministerial Group (IMG), headed by Additional Secretary (Naxal Management) was set up to oversee the effective implementation of the developmental schemes in the insurgent-infested areas.

- Naxal Management Division was brought under the MHA to oversee and provide actionable inputs.

- The government had also brought in a Unified Command to enhance the on-going anti-Naxal operations among the worst affected States – Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and West Bengal. This is unofficially called the Operation Green Hunt. The Unified Command aims to strengthen intelligence and operational coordination and launch coordinated attacks on the Maoists.

Developmental Programmes:

- COIN involves a population-centric approach to win popular support of the locals in the Maoist-infested areas.

- Since the government’s initial enemy-centric approach to deal with Naxalism failed to curb the Maoist groups completely, a series of developmental and good governance measures were taken by the government to reduce the support for insurgents.

- This approach was best illustrated in the Centre’s appointment of an expert committee to carry out a detailed study of the socio-economic development in the affected regions and suggest ways to address the deficits.

- The suggestion by the Expert Committee and the government’s own assessment had led to an unprecedented amount of resource transfer to the affected areas and the launch of the Integrated Action Plan (IAP). Later IAP was disbanded and a similar scheme – Special Central Assistance (SCA) – was launched.

- Grievances of the tribal communities were also addressed through the enactment of the Forest Dwellers Act, 2006. This was done despite the protests from environmentalists and NGOs.

- The government had also launched a new scheme, Civic Action Program (CAP), providing financial grants to the CAPFs s that they can undertake welfare activities in the Naxal-affected areas.

- Another notable scheme, Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF) was also launched to provide finance and administrative support to expand mobile services in 96 districts in 10 states.

- The issue of unemployment and illiteracy was addressed through “Skill Development in 47 LWE affected districts” and PMKVY.

- Electricity was provided to the affected villages through Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gram Jyoti Yojana.

- The Centre, under the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA), had upgraded schools and girls’ hostels have been sanctioned in 35 most affected LWE districts.

- Launched in 2018, the Aspirational Districts Programme aims to rapidly transform districts that have made less progress in key social areas.

- ROSHNI: It is a special initiative under the Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (Formerly Ajeevika Skills), which was launched in June 2013 to train and place rural poor youth from 27 LWE-affected districts across nine states.

What are the outcomes of these responses?

- While there is a difference in opinions in the nature and extent of their decline, available evidence points to a convincing decline of an insurgency that was once considered as posing a credible threat to the Indian state.

- Coordinated efforts from the Centre and Maoist-infested states have brought down LWE sponsored violence to drastic levels, which has resulted in the elimination of many important leaders of the insurgent groups and reducing the foothold of the insurgents to a handful of tri-junction districts in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha.

- Recently, about 44 districts were removed from Naxal Affected list, while the “worst affected category” was reduced from 36 to 30.

- According to reports, the Naxalite movement is facing a vacuum in the leadership, leading to the weakening of cooperation and coordination of the individual militants. The successful elimination of prominent leaders of the insurgent groups through various counterinsurgency operations has worsened the situations for the LWE groups.

- Furthermore, the coordinated response from the states on close intelligence-led operations, growing disillusionment among ideologically committed cadre and the shrinking base have hurt the CPI-Maoist’s finances.

- Demonetisation has reduced the insurgent’s ready financial resources to lure recruits, buy arms and critical equipment.

- Currently, the LWE groups are restricted to a few isolated hilly regions bordering 3 states.

- A combination of improved state actions, welfare programmes and security measures has seriously damaged the left-wing extremist operations.

- Loss of strongholds, the declining appeal of ideology and leadership crisis, along with the improved performance from the Naxal-affected states in socio-economic fronts has also led to significant improvement of counterinsurgency operations.

Conclusion

The concerted effort from both the Centre and Naxal-affected states is a rare example of cooperative federalism. Comprehensive COIN strategy, encompassing both the population-centric and enemy-centric approaches has significantly reduced the Naxal footprint in many of the militant groups in the region. Yet, the Naxalites still remain a formidable force that can nevertheless be considered a threat to India’s national security. However, unlike in the 2000s, the Indian government is well prepared in addressing this issue through a comprehensive strategy that is already in place.

Test Yourself

India’s counterinsurgency strategy is a fine example of cooperative federalism. Comment. (250 Words)

Updates

- The Director-General of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) recently stated that three states had been cleared of hotbeds of left-wing extremism (Bihar, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh). CRPF launched Operation Octopus, Operation Double Bull, Operation Thunderstorm and Operation Chakarbandha in these three States

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.