[Updated] Sabarimala Temple Issue – Customs Vs Constitution

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 80+ questions reflected

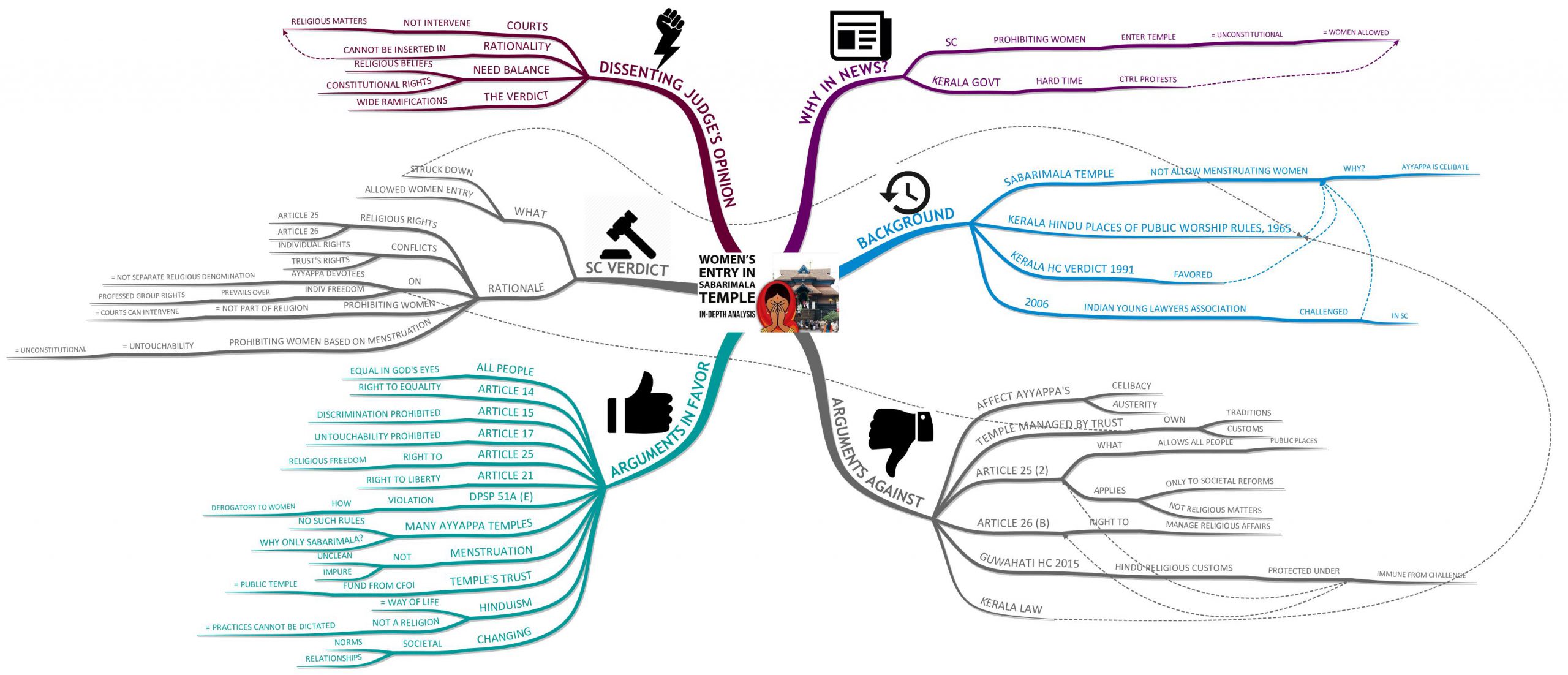

Kerala’s Sabarimala Temple issue is about the conflict between women rights and tradition. According to age-old traditions and customs, women from ten to fifty years of age were not permitted into Sabarimala Temple. However, the situation has changed when the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court on September 28, 2018, declared that restricting entry of women of menstruating age was unconstitutional. Thus the SC allowed women, irrespective of their age, to enter Sabarimala temple.

What is the background of this issue?

- The Sabarimala temple restricts menstruating women (between the age of 10 and 50 years) from taking the pilgrimage to Sabarimala. The restrictions find its source in the legend that the temple deity, Swami Ayyappa, is a ‘NaishtikaBrahmachari’ (celibate).

- Also, the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules, 1965, prohibits women from entering the Sabarimala temple premises.

- Kerala High Court in 1991 ordered in favor of the restriction by mentioning that the restriction was in place throughout history and not discriminatory to the constitution.

- In 2006, the Indian Young Lawyers Association challenged the ban in Supreme Court.

-

- However, the Kerala government appealed to the Supreme Court that the beliefs and customs of devotees cannot be altered by means of a judicial process and the priests’ opinion is final.

- Hence the Supreme Court referred the issue to a larger constitutional bench.

-

What are the arguments against women’s entry into the temple?

- Allowing menstruating women to enter the temple would affect the deity’s celibacy and austerity which is the unique nature of Swami Ayyappa.

- Temple, managed by trusts, are public places. The Sabarimala trust’s representatives claim that it has its own traditions and customs that have to be respected, just like other public places which have their own rules.

- Article 25 (2) of the constitution which provides access to public Hindu religious institutions for all classes and sections of the society can be applied only to societal reforms, not religious matters which are covered under Article 26 (b) of the Constitution. Article 26 (b) provides right to every religious group to manage their own religious affairs.

- The Guwahati High Court in Ritu Prasad Sharma Vs State of Assam (2015), ruled that religious customs which are protected under Article 25 and 26 are immune from challenge under other provisions of Part III of the constitution.

- Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules, 1965 prohibits women from entering the Sabarimala temple premises.

What are the arguments in favor of women’s entry into the temple?

- When all the people are equal in God’s eyes as well as the Constitution, there is no reason why women are only barred from entering certain temples.

- The Indian constitution under Article 25 provides an individual the freedom to choose his/her religion. Hence praying in a temple or mosque or church or at home must be the individual’s choice.

- The Constitution guarantees the right to liberty (Article 21) and religious freedom to the individual.

- There are countless Ayyappa temples in India where such rules don’t apply and there are no restrictions in praying. The deity is also being worshipped by women of these ages in their houses. Then why only Sabarimala temple?

- The argument that menstruation would pollute the temple premises is unacceptable since there is nothing “unclean” or “impure” about a menstruating woman.

- Discriminating based on the biological factor exclusive to the female gender is unconstitutional as it violates fundamental rights under Article 14 (equality), Article 15 (discrimination abolition) and Article 17 (Untouchability abolition).

- Barring women from entering the temple mainly due to their womanhood and the biological features is derogatory to women which the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) under Article 51A (e) seeks to renounce.

- The temple’s trust gets its funds from the Consolidated Fund = It is a public place of worship and not a private temple.

- Hinduism is not a religion but a way of life. Hence its practice cannot be dictated only and narrowly by religious pundits and tantric priests.

- Religious traditions must remain relevant to changing societal structures and relationships. Hence it needs reforms from within.

What is the Supreme Court Verdict?

Verdict:

In a 4-1 majority, the Supreme Court struck down provisions of the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Rules, 1965 and allowed women, irrespective of their age, to enter Sabarimala temple and worship the deity.

Rationale behind the verdict:

Religious rights

- The constitution protects religious freedom in two ways – (1) Article 25 – protects an individual’s right to profess, practice and propagate a religion, (2) Article 26 – ensures protection to every religious denomination to manage its own affairs.

- The Sabarimala case represented a conflict between the individual rights of women in the 10-50 age group to worship and the group rights of the temple authorities in enforcing the presiding deity’s strict celibate status.

- The Travancore Devaswom Board (TDB) claimed that they form a denomination and hence be permitted to make their own rules. However, the court declared that Ayyappa devotees do not constitute a separate religious denomination.

- The court ruled that prohibition on women is not an essential part of Hindu religion = Courts can intervene.

- The verdict establishes the principle that individual freedom prevails over professed group rights, even in religious matters.

Social notions

- The judgement relooks at the stigmatization of women devotees based on a medieval perspective that the menstruation symbolizes impurity and pollution.

- It declares that the exclusion on the basis of impurity is a form of untouchability.

- Further, the argument that women of menstruating age could not observe the 41-day period of abstinence failed to make any sense.

- Therefore, the court declared that any rule that segregates women due to their biological characteristics is unconstitutional.

What is the dissenting Judge’s opinion?

- The dissenting remark was given by a lone woman judge, Justice Malhotra.

- She opined that religious matters should be decided by the religious communities, rather than the court. It is because notions of rationality cannot be inserted into religious matters.

- And the balance needs to be struck between religious beliefs on one hand and constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination on the other hand.

- She also warned that the present verdict would not be restricted to Sabarimala but will have wide ramifications.

- Therefore, issues of deep religious sentiments should not be ordinarily referred to by the court.

Way ahead

This issue is an excellent opportunity for the court to reassess and reform the age-old traditions in the country which discriminates against certain sections of the society. The court should look beyond just denial of freedom of religion to women but also of equal access to public space. It will put the foundation stone for the radical re-reading of the constitution and can help the court to make a meaningful difference to people’s civil rights across caste, class, gender, and religion.

Updates – 18.11.2019

In News: The Supreme Court has decided to refer the Sabarimala temple case to a larger 7-judge Bench. This reopens not only the debate on allowing women of menstruating age into the Ayyappa temple but also the larger issue of whether any religion can prohibit women from entering places of worship.

More on the Topic:

- As the Sabarimala judgement will essentially be heard afresh, the constitutional debate on gender equality will open up once more.

- The review gives the ‘devotees’ and the Sabarimala temple authorities who have battled the Supreme Court verdict a chance to have the verdict potentially overturned.

- The larger Bench reference will also re-examine the “essential religious practice test”, a contentious doctrine developed by the court to protect only such religious practices which were essential and integral to the religion.

About the Doctrine of Essentiality:

- The doctrine of “essentiality” was invented by a seven-judge Bench of the Supreme Court in the ‘Shirur Mutt’ case in 1954. The court held that the term “religion” will cover all rituals and practices “integral” to a religion, and took upon itself the responsibility of determining the essential and non-essential practices of a religion.

- Five-judge Constitution Bench judgment in ‘Dr. M Ismail Faruqui and Others vs Union Of India and Others’ (October 24, 1994), ruled that “A mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open.”

How has the doctrine been used in subsequent years?

The ‘essentiality doctrine’ of the Supreme Court has been criticised by many constitutional experts.

- They argued that the essentiality/integrality doctrine has tended to lead the court into an area that is beyond its competence, and given judges the power to decide purely religious questions.

- As a result, over the years, courts have been inconsistent on this question,

-

-

- in some cases, they have relied on religious texts to determine essentiality.

- In others, it relied on the empirical behaviour of followers,

- and in yet others, based on whether the practice existed at the time the religion originated.

-

Note:-

The apex court in ‘Ratilal Panachand Gandhi vs The State of Bombay and Others’ (March 18, 1954) acknowledged that “every person has a fundamental right to entertain such religious beliefs as may be approved by his judgment or conscience”.

The apex court has itself emphasised autonomy and choice in its Privacy (2017), 377 (2018), and Adultery (2018) judgments.

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.

i really like your article. you presented it in very good way

Thank you so much for taking the time to appreciate my work.