National Asset Monetization Pipeline – Significance & Challenges

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

The Finance Minister announced an ambitious plan to monetize many of the government’s brownfield assets in August. This is not only to increase the government’s revenue but also to bring in private capital for infrastructure development and maintenance.

What is Asset Monetization?

- Asset monetization is the transfer of revenue rights from the government to a private party for a specific period in exchange for money, a share in the revenue and a commitment to invest in the asset.

- To understand how this works, take an example:

A person may own a grand palace but faces a lot of cost in maintaining it. Maintaining staff, security personnel, etc. for the property also costs money. There is also the need to pay taxes on such properties. As a whole, such assets can be viewed as white elephants i.e. a waste of money.

If this person were to partner up with a hotel chain via monetization, he/ she would not be losing ownership of the property but would see it refurbished and put to use as a hotel. This would bring in revenue. The hotel chain too stands to profit from such an arrangement as it wouldn’t have to build a hotel from scratch- a task requiring time, money and the effort in running around for clearances.

In short, a dead asset is monetized to enable revenue generation.

- Different methods are used to monetize assets:

- Assets in road and power sectors are monetized using structures like REITs (Real estate investment trusts) and InvITs (infrastructure investment trusts). These are even listed on the stock exchange– giving the advantage of liquidity via secondary markets.

- Monetization models based on PPP (Public Private Partnership):

- Operate Maintain Transfer (OMT)- used in highways’ monetization

- Toll Operate Transfer (TOT)- also used in monetizing highways

- Operations, Maintenance & Development (OMD)- used for monetizing airports

What is the National Monetization Pipeline?

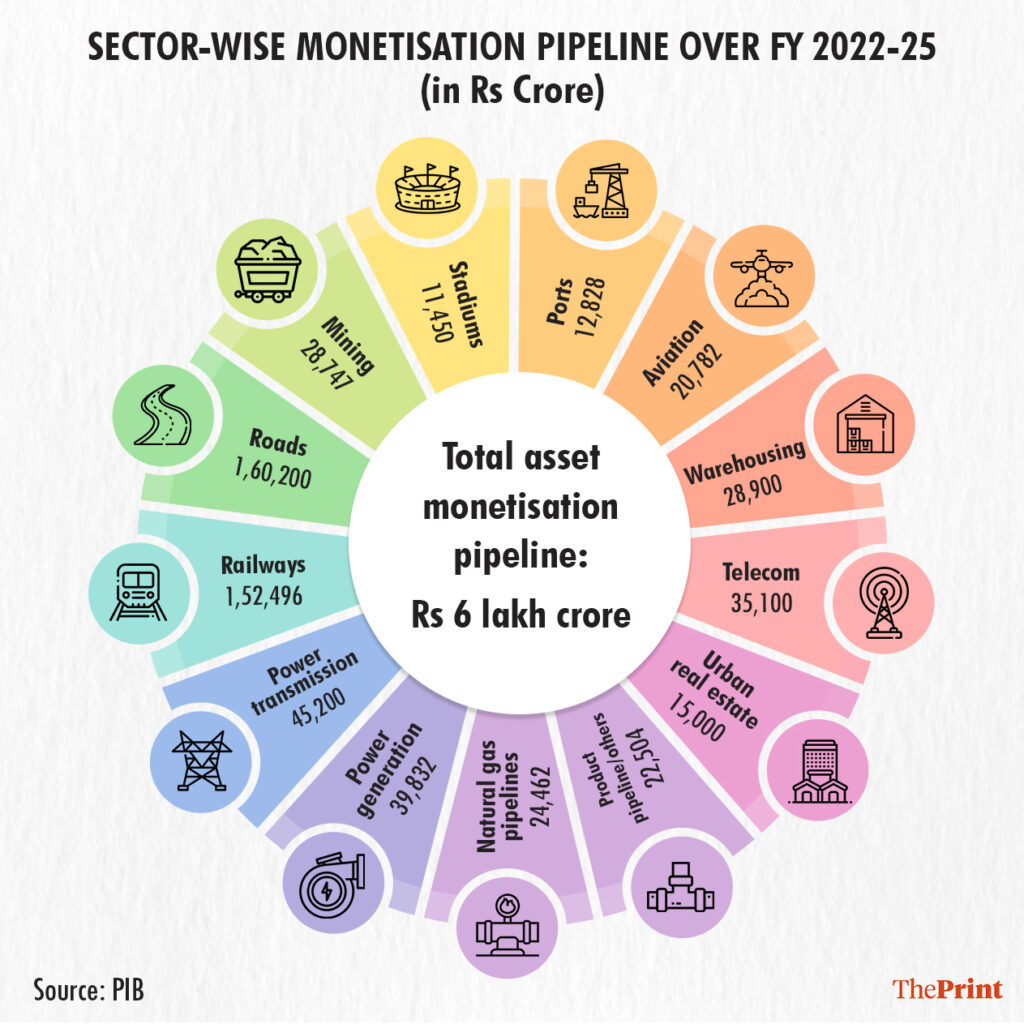

- The Finance Minister announced the Asset Monetization Plan in late August. 6 lakh crore INR has been earmarked for this ambitious project.

- It is to be co-terminous with the National Infrastructure Pipeline (launched in 2019). This means that the NMP will go on till 2025.

- The objective of this plan is to unlock the value in brownfield assets by transferring their revenue rights to private sector participants. The fund generated from this is to be used for infrastructure creation.

How is this going to be done?

- The NMP seeks to raise capital from the private sector through a direct contractual model. This means that core assets are to be leased for operation to private participants.

- Capital will also be raised through structured finance i.e. it will be accessed using pooling mechanisms like InvITs and REITs.

- Bulk of the capital will be raised by monetization of assets like roads, railways, assets of the power sector, etc.

- The government is to get a lump sum from the private sector participant in the beginning itself. This is to be used for infrastructure development under the NIP.

How is this different from privatization?

- Asset monetization is not the same as privatization of assets. In case of privatization, the government outright sells the asset to the private buyer i.e. there is transfer of ownership.

- In case of monetization, there is transfer of revenue rights to the private participant (not buyer) but not ownership. This means that there is no actual sale of the property and the government continues to own the asset in question.

- The government is simply trying to monetize the asset without selling it.

Why is this plan significant?

- The plans has been called ‘ambitious’ given its scope and budgetary allocation. The 6 lakh crore INR allocation is a lot of money- approximately 1/6th of India’s total budget.

- The plan opens up a way to address the cash crunch that holds the government agencies back from investing. Eg: the Food Cooperation of India has enormous warehouses across India. Given how logistics is set become the big business of tomorrow, modernizing these assets would be a great boon to the economy. However, many of these warehouses are poorly managed and some are so old that they have finished their lifecycle. These warehouses are in dire need of investment but the FCI is deeply in debt. This is where a plan like NMP could help.

- The plan is not only a way to generate revenue for the government in such times, but is also a way to get private sector money into the infrastructure sector and boosting the country’s infrastructural capacities.

- The government, while building numerous assets, has an unfortunate track-record of maintaining them abysmally (with the exception of some highway projects). As a result, there is a lot of loss making infrastructure projects.

- The Indian government is the biggest holder of dead assets i.e. non-revenue generating. These assets aren’t just land- the collection also includes pipelines, optical fibres, ports, airports, etc.

- Many of the dead assets lie underutilized or outright unused. On the other hand, Indian metro cities are facing a dearth of social spaces and infrastructure. As a result, there is a mushrooming of illegal infrastructure like banquet halls. Colleges and schools struggle to find sufficient space for playgrounds. The NMP is a potential solution for this mismatch problem.

- For instance, large stadiums are used barely to their 1% capacity. These stadiums (eg: Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Delhi) are world-class structures built by the government for major events like the Asian Games and the Commonwealth Games. After the event, they predominantly remain in a poor state of maintenance. A lot of effort is needed to revive them for occasional tournaments. If these stadiums could be leased, on time-share basis, under the NMP, to schools, colleges or other private players who have regular use for it, the assets find utility and generate revenue for the government while addressing the needs of the private players and the society in general.

- Bringing in the private sector would help make the assets more efficient. Eg: a private players could easily build and efficiently manage 6 docks in a port where the government is currently struggling to manage 2.

- Since only brownfield assets are used under the plan, there is a surety about their utility.

- The government has also stressed that these assets have been ‘de-risked’ from execution risks. This is bound to encourage investment from the private sector.

- Land prices could go down if the plan takes off. This will have beneficial consequences like attracting more industries and job creation.

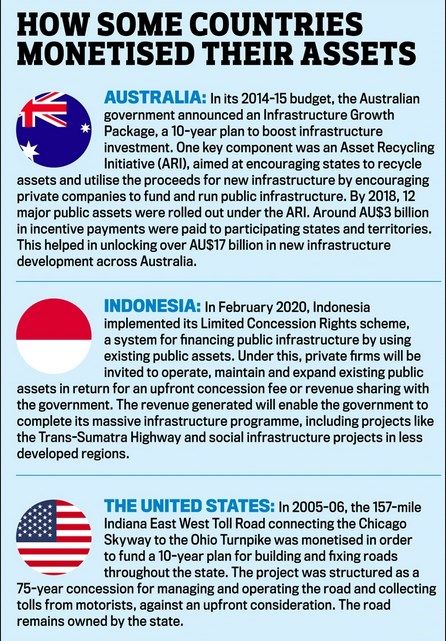

What are some other examples from around the world?

What are the challenges?

- The plan requires some 88,000 crore INR to be raised in this financial year. More needs to be raised in the next year. This is a tall order.

- Given the difficulty faced by the government in its efforts to privatize certain assets, critics have questions whether the plan is too ambitious.

- The recent situation created by the liquidity glut in the equity markets presented an opportunity for the policymakers to get great value for several assets, including Air India. However, the government kept waiting while startups with no current earnings sponged up the public capital market.

- The investors, to maximize their profits over the limited period of contract, are expected to increase the prices, cut back on maintenance and limit competition. Eg: In Singapore, the government had to nationalize the suburban trains and signalling systems after it started facing frequent breakdowns, leaving the passengers stranded and angry. This is because its main private operator under-invested in the system’s maintenance.

- There is a concern that the lump-sum gain of today would become a cost to the government tomorrow. Eg: In New South Wales, the government had to intervene with an Energy Affordability Package to alleviate the burden on consumers after the electricity prices shot up by two-fold in 5 years following the privatization of poles and wires. The Indian government cannot afford largesse in case of similar occurrence here.

- There is also concern that the plan would lead to concentration of economic power in a few large private players. Several sectors are already witnessing a reduction in diversity of players. Eg: the wireless carriage business in now effectively a duopoly.

- Some of the players that are expected to bid for assets under the plan include Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Singaporean sovereign wealth fund GIC Pte., Australia’s Macquarie Group Ltd. and also local financial institutions. Even if they win some bids, they may never be on par with domestic business groups that have the ability to sway regulations.

- Critics have expressed concern over the gaps in institutional maturity. Though India has established investment trusts and TOT structures, there are questions about the lack of legal and regulatory mechanisms to truly de-risk infrastructure- especially politically sensitive ones.

- Weak regulators can bring in their own risks to the equation even if progress has been made on the fronts of land acquisition, environmental clearance and construction.

- The space for constructive discussions during the tender process is limited in India. There are fears around accusations of unfair dealings and collusions. As a result, the public authorities are reluctant to address the genuine commercial concerns of private bidders.

- The PPP model is not glitch free. Eg: the PPP models used in the power grid, NHAI and the airports aren’t very successful and require re-appraisal.

- Since there is no transfer of ownership to the private participant, the asset will not show up on its balance sheet. This may lead to issues for the private sector in terms of credit and investment. Eg: there are confusions about whether or not the private participant would be able use the asset as a collateral to raise funds from investors or the market.

- There are fears that the revenue may be used (fully/ partially) for repaying loans, debt servicing or for bailing out public sector banks from their NPA problems. If that happens, the citizens’ confidence in the banking system would be seriously eroded and the hardworking companies of the business community would lose incentive to conduct clean business.

- Resistance from public sector entities that own these assets.

- Land is state subject. Here cooperation with the state government becomes crucial.

What is the way ahead?

- Many have called for outright privatization but there has been reluctance from the government side due to fear of allegations of collusion. Hence, monetization can be seen as the next best route.

- Regulatory acumen and bureaucratic capability are key to keeping the NMP from becoming a transfer of assets, funded by the taxpayer, to a small group of private players.

- The government should assure the public that none of the realized revenue will be used for bailing out NPAs or for building more white elephants intended to cater to vote banks and identity politics.

- A white paper explaining the revenue avenues and outflows in the NMP is needed from the Niti Aayog or the Finance Ministry. It could also provide a roadmap for new asset creation.

- Another area where transparency is vital is asset valuation and the tendering process.

- Also, the government announced plans to launch an online platform as part of the asset monetization drive. It is to enable transparent sale of surplus land and properties of PSUs. The state-run MSTC is to set up an e-bidding facility to auction off the non-core assets of the PSUs. This is a positive step in ensuring transparency.

- The PPP model needs to be made fool-proof before making it the standard practice.

- There is a need for mind-set change to recognize that the bedrock of private commercial endeavour is profit. But profit-seeking is not a zero-sum game that trades off public interest. Contractual frameworks on equal footing (i.e. the state should be a counter-party– not the sovereign here) can help create win-win partnerships.

- The state needs to separate its asset-owing role from its regulatory role to ensure proper justice in conflict resolution in PPPs. The legislature may consider bringing in a special legal framework for governing PPPs to help this process.

- Such a law can also consider changing the basis for contract allocation from ‘bidder with highest bid’ to ‘bidder who is best able to invest in and improve’ the project throughout the contract period.

- Need to note that one-sided contracts that favour the public authority don’t necessarily serve the public interest. This is because failure of a public project hurts, not only the private participant, but also the project’s users and its financial backers.

- The framework must make room for flexibility in contractual terms. This is because PPPs tend to span many decades and the initial terms may not cater to the needs of potential future events. For instance, Brazil recently introduced provisions for periodic review and mandatory contract revision in its PPPs.

- The framework for contract amendment must be principle-based, as opposed to rule-based. It should allow for constructive discussion among the key stakeholders.

- Independent regulatory bodies for PPPs could help too. It should have well-defined parameters such as standards setting, tariff setting, etc.

- Auction process needs to be better prescribed. For instance, the European Commission’s directives stipulate different procedures for auctions, which are customized by public authority according to the project in question.

- With regards to bringing the states on-board, the government announced plans to incentivize state governments to monetize their assets. This is over and above the 6 lakh crore INR program.

- The asset monetization and infrastructure development must be sustainable and socially sensitive.

Conclusion

‘Govt should not be in the business of running any business’ has become an adage. In addition to this, India needs infrastructural development to achieve its aspirations of becoming a 5 trillion dollar economy by 2024-25. For this, private sector participation is crucial. In this regard, the NAMP is a step in the right direction. However, the government needs to do further homework on the intent, content and methodology of the plan before rolling it out.

Practice question for mains

The NAMP is criticised as government resorting to ‘fire sale’ and ‘selling the family silver’. Examine the necessity of asset monetization. What are the challenges and way forward? (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.