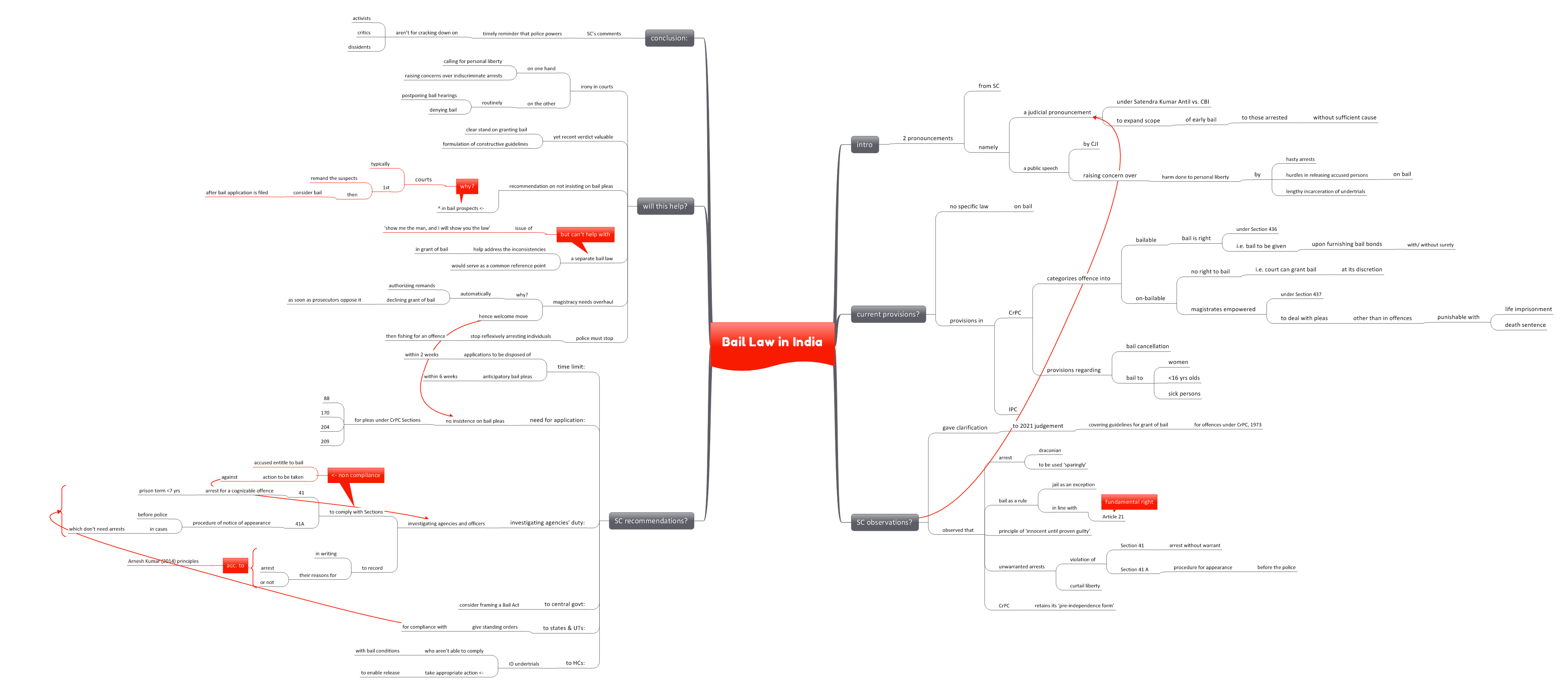

Bail Law in India

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

Recently, 2 pronouncements from the Supreme Court have brought the country’s bail law into focus. One is a judicial pronouncement, under Satendra Kumar Antil vs. CBI, which sought to expand the scope of early bail to those arrested with insufficient cause and the other is a public speech, by Chief Justice of India, raising concern over the harm done to personal liberty by hasty arrests, hurdles in releasing accused persons on bail and lengthy incarceration of undertrials.

What are the current provisions?

- Currently, there isn’t a specific law defining bail and providing for it.

- However, the concept is covered by the CrPC and IPC provisions.

- CrPC categorizes offences into bailable and non-bailable offences.

-

- Bailable offences:

-

- According to Section 436, bail is a right for those accused of a bailable offence.

- The police/ the court (whoever has the person’s custody) is mandated to release the accused after the furnishing of a bail bond. This bond may be with/ without surety.

-

- Non-bailable offences:

-

- For such offences, there is no right to bail.

- The courts has the discretion to release the accused on bail.

- The Magistrate has powers to deal with pleas, according to Section 437. However, this doesn’t apply to offences punishable with life imprisonment or death.

- The CrPC also has provisions regarding the cancelation of bails.

- Another provision covers the grant of bail to accused persons below 16 years of age, sick suspects and female suspects.

What are the Supreme Court’s observations?

- The SC recently gave clarifications to a 2021 judgement in Satendra Kumar Antil vs. CBI. It covers the guidelines for grant of bail for offences under CrPC, 1973.

- The Apex Court held that arrest is a ‘draconian measure’. It is to be used ‘sparingly’.

- It held that bail is to be the rule and jail, an exception. This is in line with the provisions of Article 21.

- The court also highlighted the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

- It said that unwarranted arrests are being carried out, violating CrPC’s Section 41 (arrest without warrant) and Section 41 A (procedure for appearance before the police). These curtail liberty.

- It noted that the CrPC, despite its modifications, retains its ‘pre-independence form’.

What did the court recommend?

- The court stressed the need to follow due procedure for arrests and a time limit while disposing bail applications.

Time Limit:

- Bail applications are to be disposed of within 2 weeks. Exceptions to this time limit are to be allowed only when provisions mandate them.

- Anticipatory bail pleas are to be decided within 6 weeks.

Need for Application:

- When considering pleas under CrPC Sections 88, 170, 204 and 209, there needn’t be any insistence on bail pleas.

Investigating Agency’s Duty:

- The court called on the investigating agencies and officers to comply with Sections 41 (deals with arrest for a cognizable offence which calls for a prison term of less than 7 years) and 41A (which deals with procedure of notice of appearance before the police in cases which don’t require an arrest) of CrPC.

- Non-compliance with these sections would entitle the accused person to bail.

- The court said that any dereliction of duty will invite actions.

- Police officers are required to record their reasons for arrest (or not) in writing. This is in accordance with Arnesh Kumar (2014) principles.

To the Central Government:

- The court has asked the central government to consider framing a Bail Act, to streamline the bail process in India.

To the State & UT Governments:

- The state and UT governments are to give standing orders for compliance with Sections 41 and 41A.

To High Courts:

- High Courts are to identify undertrials who aren’t able to comply with the bail conditions. Then, they are to take appropriate action to enable their release.

How far would this help address the issues?

- Critics have pointed out to the irony in courts calling for personal liberty and raising concerns over indiscriminate arrests on one hand, while routinely postponing bail hearings or denying them altogether on the other hand.

- Yet, the recent verdict’s stand on granting bail and formulation of constructive guidelines for arrest is valuable.

- The court’s recommendation on not insisting on bail pleas, under certain sections of the CrPC, would significantly increase an accused person’s bail prospects. This is because courts typically remand the suspects and consider bail, only after the filing of a bail application.

- The court’s call for a separate bail law would help address the inconsistencies in who gets bail. Such a law, would serve as a common reference point, for the courts and the investigating agencies.

- However, critics have raised concern over whether a law can address the problem of ‘show me the man, and I will show you the law’.

- The magistracy is in need of an overhaul. Magistrates seem to automatically authorize remand whenever an accused is produced before them and to decline grant of bail as soon as prosecutors oppose it. Hence, the court’s recommendation that bails be considered even in the absence of a formal application is a welcome move.

- In addition to this, the police must stop reflexively arresting individuals and then fishing for an offence.

Conclusion:

The SC’s comments are a timely reminder that police powers aren’t for cracking down on activists, critics and dissidents.

Practice Question for Mains

What are the issues plaguing the bail system in India? What are the Supreme Court recommendations to address these issue? (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.