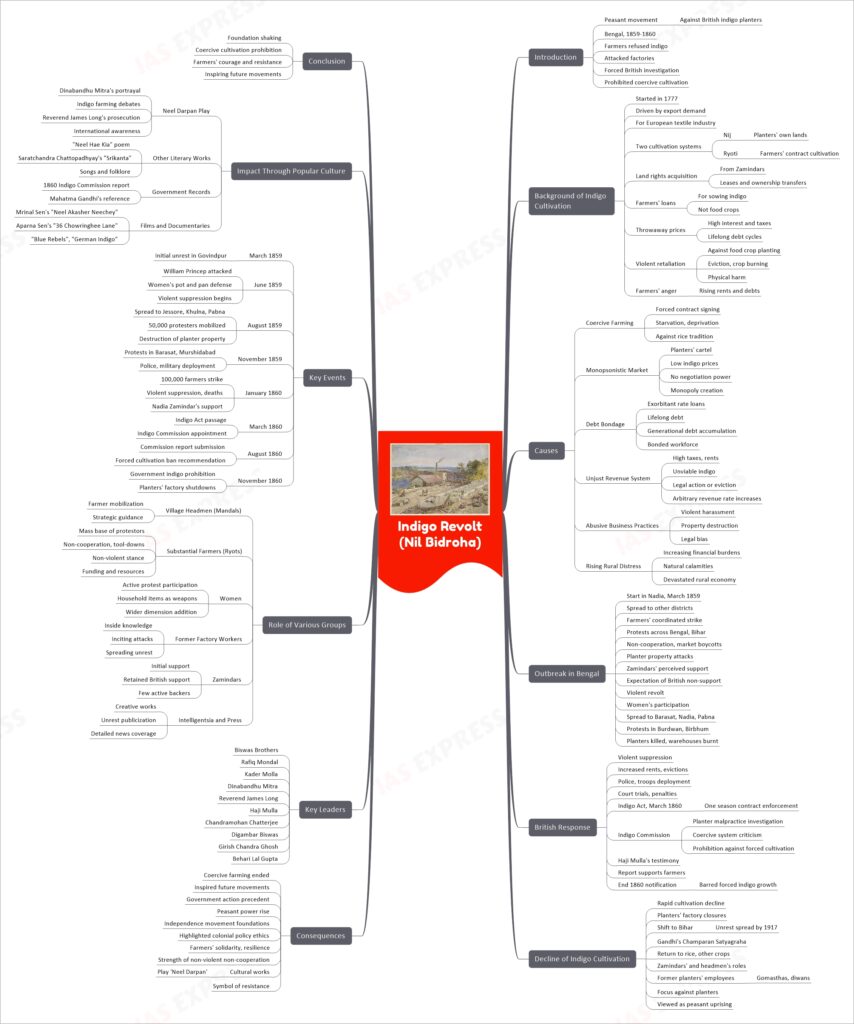

Indigo Revolt of 1859-60 – Causes, Events, Outcomes

Introduction

The Indigo revolt, also known as the Nil Bidroha, was a peasant movement against the exploitative practices of British indigo planters in Bengal from 1859-1860. Thousands of farmers refused to grow indigo and attacked indigo factories in protest. The revolt spread across Bengal and forced the British colonial government to investigate and eventually prohibit the coercive indigo cultivation system.

Background of Indigo Cultivation

- Indigo cultivation started in Bengal in 1777 driven by export demand for natural blue dye from the European textile industry.

- Two systems of indigo cultivation existed – Nij where planters produced indigo on their own lands, and Ryoti where farmers grew indigo on contract and sold to planters.

- Planters acquired land rights from Zamindars through leases and ownership transfers to expand indigo farming.

- Farmers were given loans by planters to sow indigo instead of food crops on portions of their land as per signed contracts.

- Farmers had to sell the indigo to planters at throwaway prices, couldn’t repay loans due to high interest and taxes, and got trapped in lifelong debt cycles.

- Some farmers who planted food crops instead faced violent retaliation from planters including eviction, crop burning, and physical harm.

- The inherently exploitative system angered farmers who were struggling under rising rents and debts.

Causes

The major causes leading to the Indigo Revolt were:

Coercive Farming

- Farmers forced to sign indigo sowing contracts binding their best lands.

- Couldn’t grow food crops leading to starvation and deprivation.

- Against tradition of growing rice which sustained the community.

Monopsonistic Market

- Planters formed cartel fixing very low indigo prices unfair to farmers.

- Farmers couldn’t negotiate better rates due to lopsided power.

- Local markets and outside buyers not allowed creating monopoly.

Debt Bondage

- Loans at exorbitant rates trapped farmers in lifelong debt cycles.

- Debt accumulation over generations crated a bonded workforce.

- Even children inherited debt driving families to penury.

Unjust Revenue System

- High taxes, rents, and interest repayments made indigo unviable.

- Farmers defaulting on any payment faced legal action or eviction.

- Planters increased revenue rates arbitrarily to maximize profits.

Abusive Business Practices

- Farmers harassed violently for refusing work or destroying indigo.

- Crops uprooted, houses burnt down, and families attacked.

- Legal system always sided with planters against oppressed farmers.

Rising Rural Distress

- Increasing rents, taxes, and interest rates burdened farmers.

- Natural calamities like drought and flood worsened the distress.

- Falling income from indigo cultivation devastated rural economy.

Outbreak in Bengal

- The revolt started in March 1859 in Nadia district where farmers refused to sow indigo.

- It quickly spread to other districts as farmers launched a coordinated strike.

- By end 1859 lakhs of farmers across Bengal and Bihar had joined the protests.

- Farmers used non-cooperation, market boycotts, tool-downs, and attacks on planter property as protest tactics.

- They were emboldened by perceived support from zamindars who resented planters’ rising power.

- Farmers also expected the British government won’t back planters if protests erupted.

- The revolt turned violent as farmers armed themselves to attack indigo factories, burn crops, and resist police.

- Women participated enthusiastically using domestic items as weapons against planters.

- In April 1860 mass strikes spread across Barasat, Nadia, and Pabna districts.

- Protests also erupted in Burdwan, Birbhum, Khulna, Murshidabad, and Narail.

- Some planters were killed in public trials while farmers set ablaze indigo warehouses.

British Response

- Planters tried to violently suppress protests using mercenaries and clashing with farmers.

- They increased rents arbitrarily and evicted more farmers to retaliate.

- Large numbers of police and troops were deployed to curb the unrest.

- Hundreds of farmers were tried in court by planters seeking huge penalty payments.

- In March 1860, the Bengal government passed the Indigo Act enforcing indigo contracts for one season.

- The Act also established an Indigo Commission to investigate planter malpractices.

- The Commission found the coercive indigo system exploitative and flawed.

- It prohibited forcing farmers to cultivate indigo against their will.

- A key witness Haji Mulla told the Commission he would rather beg than sow indigo again.

- The Commission report criticized planters’ practices and supported farmers’ right to grow crops.

- By end 1860 a notification barred compelling farmers to grow indigo.

Decline of Indigo Cultivation

- After the Commission findings, indigo cultivation rapidly declined in Bengal.

- With no support from the authorities, planters closed their factories and left Bengal.

- Indigo farming shifted to Bihar state but unrest spread there too by 1917.

- Gandhi led the Champaran Satyagraha movement in Bihar against exploitative indigo policies.

- Bengal’s farmers returned to growing rice and other crops bringing great relief.

- Zamindars and village headmen played key roles in sustaining the revolt by mobilizing farmers.

- Former employees of planters known as gomasthas and diwans lent their experience to build resistance.

- The revolt was largely focused against planters rather than the colonial government.

- Historians see it as a pure peasant uprising unlike the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny with wider aims.

Consequences

- The Indigo Revolt was a huge success though violently suppressed, as it ended coercive farming.

- It inspired future peasant movements against colonial exploitation like Champaran, Bardoli, Moplah.

- It set a precedent of government action to protect farmer interests.

- It marked the rise of peasant power and laid foundations of India’s independence movement.

- It highlighted the unethical aspects of colonial policies to the world.

- The farmers’ solidarity and resilience during the protests were exemplary.

- It showed the strength of non-violent non-cooperation against injustice.

- It led to many cultural works like the play ‘Neel Darpan‘ on indigo farmer woes.

- It is seen as a symbol of resistance inspiring discussions on social justice even today.

Key Leaders

Some prominent leaders who led the Indigo Revolt were:

- Biswas Brothers: Wealthy family of farmers from Nadia who helped trigger the initial unrest among ryots.

- Rafiq Mondal: A headman from Bardhaman district who actively mobilized local peasants against planters.

- Kader Molla: A disgruntled former factory worker from Pabna who attacked and destroyed indigo depots.

- Dinabandhu Mitra: Bengali dramatist who highlighted farmer suffering through his play ‘Neel Darpan’.

- Reverend James Long: An Irish missionary who supported the Nadia peasants and publicized their grievances.

- Haji Mulla: A witness at Indigo Commission hearings who said he would rather beg than sow indigo.

- Chandramohan Chatterjee: Represented Zamindars at the Indigo Commission arguing for ryot rights.

- Digambar Biswas: Powerful Zamindar from Nadia who provided strategic support to protesting farmers.

- Girish Chandra Ghosh: Assisted Mitra with ‘Neel Darpan’ and took the banned play across Bengal.

- Behari Lal Gupta: Young lawyer who defended hundreds of arrested farmers pro bono in indigo cases.

Role of Various Groups

Different groups played important roles during the Indigo Revolt:

Village Headmen (Mandals)

- Local leaders who actively mobilized farmers against planters’ exploitation.

- Persuaded ryots to strike work and attack factories in the initial spark.

- Continued supporting protests through strategic guidance and resources.

Substantial Farmers (Ryots)

- Made up the mass base of protestors across Bengal districts.

- Used non-cooperation, tool-downs, economic boycotts as main tactics.

- Maintained non-violent stance mostly though some attacks did happen.

- Provided funds and resources to sustain year-long movement.

Women

- Actively participated in protests to support families.

- Used household items like pots and pans as weapons against planters.

- Their involvement added wider dimension to the revolt.

Former Factory Workers (Gomasthas, Diwans)

- Provided inside knowledge of planter operations to revolt leaders.

- Incited attacks on indigo warehouses and factories.

- Spread unrest across districts owing to their mobility.

Zamindars

Initially supported revolt as they resented planters’ rising power.

- But mostly remained aloof to retain British support for land rights.

- A few powerful ones like Digambar Biswas actively backed farmers.

Intelligentsia and Press

- Playwrights, writers highlighted farmers’ misery through creative works.

- Missionaries publicized the unrest to criticize Company exploitation.

- Newspapers covered events in detail spurring public debates.

Key Events

Some major events that characterized the Indigo Revolt were:

March 1859

- Farmers of Govindpur village, Nadia refused to sow indigo.

- This sparked the initial unrest among indigo ryots.

- Anger spread rapidly to other villages as farmers joined strike.

June 1859

- British planter William Princep attacked by mob of protesters in Govindpur.

- Women used pots and pans to drive away manager of a factory.

- Violent suppression by police and planters’ guards began.

August 1859

- Revolt spread to Jessore, Khulna, and Pabna districts through summer.

- Over 50,000 protesters mobilized by Nadia headmen.

- Planters’ crops destroyed and warehouses burnt down.

November 1859

- Large protests erupted in Barasat, Murshidabad, Birbhum, and Burdwan.

- Indigo depots attacked and European staff assaulted in Pabna.

- Government deployed police and military to curb unrest.

January 1860

- Over 100,000 farmers on strike refusing to sow indigo.

- Violent suppression continued leading to many deaths.

- Nadia Zamindar Digambar Biswas supported protests in his estates.

March 1860

- Indigo Act passed enforcing indigo contracts temporarily.

- Indigo Commission appointed to enquire into planter malpractices.

August 1860

- Commission report submitted criticizing coercive indigo system.

- Recommended banning forced indigo cultivation.

November 1860

- Government notification prohibited compelling farmers to grow indigo.

- Planters started shutting down indigo factories in Bengal.

Impact Through Popular Culture

The Indigo Revolt and farmers’ misery became widely known through contemporary popular cultural portrayals:

Neel Darpan Play

- Dinabandhu Mitra’s play “Neel Darpan” portrayed the misery of indigo farmers under planters.

- It sparked intense debates on indigo farming practices and ryots’ plight.

- The play was translated into English leading to the translator Reverend James Long’s prosecution for sedition.

- But it highlighted the Indigo Revolt across India and abroad.

Other Literary Works

- Poems like “Neel Hae Kia” by Biharilal Chakravarti depicted farmers’ woes.

- Novels like Saratchandra Chattopadhyay’s “Srikanta” referenced indigo farmer struggles.

- Songs and folklore kept the movement’s memory alive in rural Bengal.

Government Records

- The 1860 Indigo Commission report exposed the coercive system.

- It was widely cited by Indian leaders over decades.

- Mahatma Gandhi referenced it during his 1917 Champaran satyagraha.

Films and Documentaries

- Mrinal Sen’s film “Neel Akasher Neechey” showed the revolt’s impact on peasants.

- Aparna Sen’s “36 Chowringhee Lane” had indigo farming as a plot element.

- Documentaries like “Blue Rebels” and “German Indigo” revisited the episode.

Conclusion

The Indigo Revolt, though violently crushed, shook the foundations of exploitative colonial policies in India. It highlighted the oppressive nature of the coercive indigo cultivation system and led to its prohibition. The farmers’ remarkable courage and resistance during the protests continue to inspire peasant movements against injustice even today.