Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) – The Fundamental Rights Case

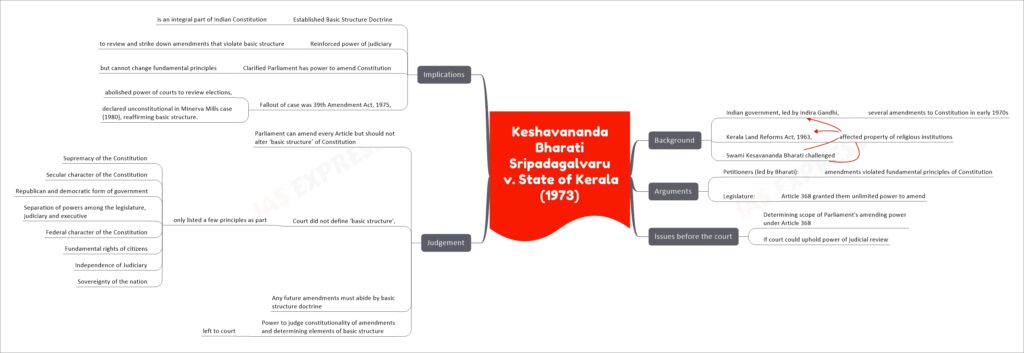

Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala is one of the most significant cases in Indian constitutional history. The case dealt with the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution, specifically the question of whether Parliament could alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution. The case is popularly known as the case of the fundamental rights and is considered one of the longest and most important cases in India.

Background

- In the early 1970s, the Indian government, led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, enacted several amendments to the Constitution, including the 24th, 25th, 26th and 29th amendments.

- These amendments were intended to overcome previous Supreme Court judgments, such as the Golak Nath case in 1967, which had limited the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution, particularly with respect to fundamental rights.

- The Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963, which was intended to improve the social and economic conditions of the state, had also begun to affect the property of several religious institutions in India, including the one headed by Swami Kesavananda Bharati.

- In 1970, Bharati challenged the land reforms of Kerala and the constitutional validity of the 24th, 25th and 29th amendments in the Supreme Court on the grounds that they violate the fundamental rights given under Article 14, 19(1)(f), 25, 26 of the Indian Constitution.

Arguments

- The petitioners, led by Bharati, argued that the amendments violated the fundamental principles of the Constitution that were the pillars of Indian democracy.

- They contended that the legislature was not authorized to modify those provisions by drawing power from the Constitution itself.

- The legislature, on the other hand, argued that Article 368 granted them unlimited power to amend.

Issues before the court

- The main issue in the case was determining the scope of Parliament’s amending power under Article 368 of the Constitution.

- Specifically, the court had to decide whether the power of Parliament was unfettered or if the court could uphold its power of judicial review.

Judgement

- Parliament can amend every Article in the Constitution but should be restrained from altering the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution.

- The court did not define the ‘basic structure’, and only listed a few principles listed below as being its part. Since then, the court has been adding new features to this concept.

- Supremacy of the Constitution

- Secular character of the Constitution

- Republican and democratic form of government

- Separation of powers among the legislature, judiciary and executive

- Federal character of the Constitution

- Fundamental rights of citizens

- Independence of Judiciary

- Sovereignty of the nation

- The court made use of a teleological approach to protect the identity and framework of the Constitution.

- It was thereby decided that any future amendments after the case would have to abide by the basic structure doctrine.

- The power to judge the constitutionality of those amendments and determining the elements of the basic structure was left to the court itself.

Implications of the case:

- The case established that the Basic Structure Doctrine is an integral part of the Indian Constitution and that the Parliament cannot alter or destroy the basic structure of the Constitution through its amendment power.

- It also reinforced the power of the judiciary to review and strike down amendments that violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

- The case also clarified that the Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, but it cannot change the fundamental principles of the Constitution.

- The fallout of the Kesavananda Bharati case was that the Indira Gandhi government struck back with the 39th Amendment Act, 1975, which abolished the power of the courts to review the election of the Prime Minister and other high functionaries. However, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in the Minerva Mills case (1980), thereby reaffirming the basic structure doctrine.

Glossary

| Article 13(2): prevents the state from creating any laws that take away fundamental rights. Article 14: Right to Equality Article 19(1)(f): Right to own and manage property Article 25: Right to freedom of conscience and free profession, practice and propagation of religion Article 26: Freedom to manage religious affairs Article 31B: Protection of laws giving effect to certain directive principles in the 9th schedule Golak Nath case: a 1967 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Parliament could not amend any of the fundamental rights in the Constitution. Shankari Prasad case: a 1951 case in which the Supreme Court upheld the right to property as a fundamental right and ruled that the Constitution could not be amended to take away this right. Sajjan Singh case: a 1965 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution could not be amended to take away the right to property. Minerva Mills case of 1980: further clarified the concept of the Basic Structure Doctrine established in Kesavananda Bharati, by upholding the right to equality as a fundamental part of the Basic Structure of the Constitution, and also held that any amendment to the Constitution that seeks to damage the basic structure would be considered unconstitutional. |

This article is part of the series “Landmark Judgements that Shaped India” under the Indian Polity Notes & Prelims Sureshots. We aim to make the articles comprehensive while leaving out unnecessary information from the UPSC perspective. If you think this article is useful, please provide your feedback in the comments section below.