Minority institutions in India: SC Ruling & Implications

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

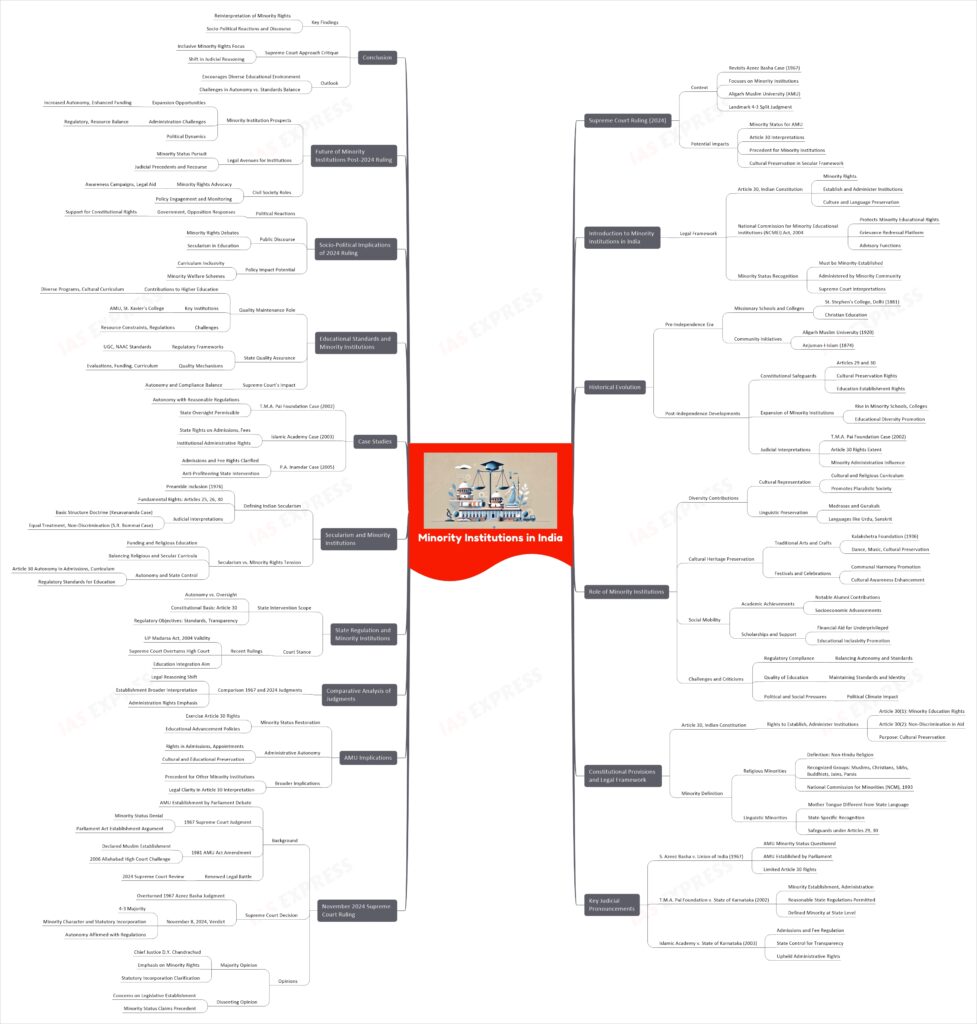

The recent Supreme Court ruling of November 2024, which revisits the 1967 Azeez Basha case, has reignited discussions on minority institutions in India, particularly in the context of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). This landmark judgment, marking a 4-3 split, has the potential to restore AMU’s minority status, overturning long-held interpretations of Article 30, which protects minorities’ rights to establish and administer educational institutions. The decision is seen as a critical shift, prompting debates on the balance between minority autonomy and state regulation. This ruling not only impacts AMU but sets a precedent for minority institutions across India, underscoring their role in preserving cultural identity within a secular framework.

Introduction to Minority Institutions in India

Legal Framework and Constitutional Provisions

- Article 30 of the Indian Constitution: Grants religious and linguistic minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice, ensuring the preservation of their culture and language.

- National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI) Act, 2004: Established the NCMEI to protect and promote the educational rights of minorities, providing a platform for grievance redressal and advisory functions.

- Minority Status Recognition: Institutions must be established and administered by a minority community to claim minority status, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in various judgments.

Historical Evolution of Minority Educational Institutions

- Pre-Independence Era

- Missionary Schools and Colleges: Christian missionaries established institutions like St. Stephen’s College in Delhi (founded in 1881) to provide education aligned with their religious beliefs.

- Community Initiatives: Communities such as Muslims and Parsis founded institutions like Aligarh Muslim University (established in 1920) and Anjuman-I-Islam (founded in 1874) to cater to their educational needs.

- Post-Independence Developments

- Constitutional Safeguards: The inclusion of Articles 29 and 30 in the Constitution provided minorities with rights to preserve their culture and establish educational institutions.

- Expansion of Minority Institutions: Post-1947, there was a significant increase in minority-run schools and colleges across India, contributing to educational diversity.

- Judicial Interpretations: Landmark cases like T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka (2002) clarified the extent of rights under Article 30, influencing the administration of minority institutions.

Role of Minority Institutions in India’s Educational Landscape

- Contribution to Diversity

- Cultural Representation: These institutions offer curricula that include cultural and religious teachings, promoting a pluralistic society.

- Linguistic Preservation: Schools like the Madrasas and Gurukuls help in preserving languages such as Urdu and Sanskrit.

- Preservation of Cultural Heritage

- Traditional Arts and Crafts: Institutions like the Kalakshetra Foundation (established in 1936) focus on traditional dance and music forms, preserving cultural heritage.

- Festivals and Celebrations: Minority institutions often celebrate cultural festivals, fostering communal harmony and cultural awareness among students.

- Educational Excellence and Social Mobility

- Academic Achievements: Many minority institutions have produced notable alumni contributing to various fields, enhancing the community’s socio-economic status.

- Scholarships and Support: These institutions often provide financial aid to underprivileged students, promoting inclusivity and access to education.

- Challenges and Criticisms

- Regulatory Compliance: Balancing autonomy with adherence to national educational standards remains a challenge.

- Quality of Education: Ensuring high educational standards while preserving cultural identity is a continuous endeavor.

- Political and Social Pressures: Minority institutions sometimes face challenges due to changing political climates and societal perceptions.

Constitutional Provisions and Legal Framework

Article 30 of the Indian Constitution

- Rights of Minorities to Establish and Administer Educational Institutions

- Article 30(1): Grants all minorities, whether based on religion or language, the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

- Article 30(2): Prohibits the state from discriminating against any educational institution managed by a minority while granting aid.

- Objective: Ensures minorities can preserve their culture, language, and religion through education.

Interpretation of ‘Minority’ in the Indian Context

- Religious Minorities

- Definition: Communities practicing religions other than the majority religion, Hinduism.

- Recognized Religious Minorities: Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, and Zoroastrians (Parsis).

- National Commission for Minorities (NCM): Established in 1993 to safeguard the rights of these communities.

- Linguistic Minorities

- Definition: Groups whose mother tongue is different from the principal language of the state or region.

- Recognition: Varies across states; a community may be a linguistic minority in one state but not in another.

- Safeguards: Articles 29 and 30 protect their rights to conserve their language and establish educational institutions.

Key Judicial Pronouncements Shaping Minority Rights

| Case Name | Year | Key Issues Addressed | Impact on Minority Rights |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. Azeez Basha v. Union of India | 1967 | Whether Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) was established by the Muslim minority | Held that AMU was established by an Act of Parliament, not by the Muslim community; limited the scope of Article 30 rights. |

| T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka | 2002 | Scope of rights under Article 30; definition of ‘minority’; extent of state regulation | Clarified that minorities can establish and administer institutions; state can impose reasonable regulations; defined ‘minority’ at the state level. |

| Islamic Academy of Education v. State of Karnataka | 2003 | Implementation of T.M.A. Pai judgment; regulation of admissions and fees in minority institutions | Affirmed state authority to regulate admissions and fees to ensure merit and transparency; upheld minority rights to administer institutions. |

The November 2024 Supreme Court Ruling: An Overview

Background of the Case: Aligarh Muslim University’s Quest for Minority Status

- Establishment and Historical Context

- Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), founded in 1920 in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, evolved from the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College established by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in 1875.

- The institution aimed to provide modern education to Muslims while preserving Islamic culture and traditions.

- 1967 Supreme Court Judgment: S. Azeez Basha v. Union of India

- The Supreme Court ruled that AMU was established by an Act of Parliament, not by the Muslim community, thereby denying it minority status under Article 30 of the Constitution.

- Subsequent Developments

- In 1981, Parliament amended the AMU Act, declaring that the university was established by Muslims, aiming to restore its minority status.

- However, in 2006, the Allahabad High Court struck down this amendment, reaffirming the 1967 judgment.

- Renewed Legal Battle

- AMU and various stakeholders continued to challenge the denial of minority status, leading to the Supreme Court revisiting the issue in 2024.

Supreme Court’s Decision: Overturning the 1967 Azeez Basha Judgment

- November 8, 2024, Verdict

- A seven-judge Constitution Bench delivered a 4-3 majority judgment overturning the 1967 ruling.

- The court held that the mere fact of incorporation by a statute does not negate the institution’s minority character if it was established by a minority community.

- Key Findings

- Establishment by Minority Community: Recognized that AMU was established by Muslims, fulfilling the criteria under Article 30.

- Statutory Incorporation: Clarified that legislative incorporation does not strip an institution of its minority status.

- Autonomy in Administration: Affirmed the rights of minority institutions to administer their affairs, subject to reasonable regulations.

Majority and Dissenting Opinions: Analysis of the 4-3 Split Verdict

- Majority Opinion

- Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud authored the majority judgment, joined by Justices Sanjiv Khanna, J.B. Pardiwala, and Manoj Misra.

- Emphasized the intent of Article 30 to protect minority rights and preserve their educational institutions.

- Stated that statutory incorporation is a common method for establishing universities and does not affect their minority status.

- Dissenting Opinion

- Justices Surya Kant, Dipankar Datta, and S.C. Sharma dissented.

- Argued that AMU’s establishment through an Act of Parliament indicates it was not founded by the Muslim community.

- Expressed concerns about setting a precedent that could lead to widespread claims of minority status by institutions established by legislation.

Implications for AMU: Potential Restoration of Minority Status and Autonomy in Administration

- Restoration of Minority Status

- The ruling paves the way for AMU to reclaim its minority status, allowing it to exercise rights under Article 30.

- Enables the university to implement policies favoring the educational advancement of the Muslim community.

- Autonomy in Administration

- Affirms AMU’s right to manage its affairs, including admissions, faculty appointments, and curriculum design, within the framework of reasonable regulations.

- Enhances the university’s ability to preserve its cultural and educational objectives.

- Broader Impact on Minority Educational Institutions

- Sets a precedent for other institutions seeking minority status, potentially leading to a re-evaluation of their legal standing.

- Clarifies the legal interpretation of ‘establishment’ and ‘administration’ under Article 30, influencing future judicial decisions.

This landmark judgment marks a significant shift in the legal landscape concerning minority educational institutions in India, reaffirming the constitutional protections afforded to them.

Comparative Analysis of Precedent and the 2024 Ruling

Comparison between the 1967 and 2024 Supreme Court Judgments

| Aspect | 1967 Judgment (S. Azeez Basha v. Union of India) | 2024 Judgment (Aligarh Muslim University Minority Status Case) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Reasoning | Determined that Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) was established by an Act of Parliament, not by the Muslim community, thereby denying it minority status under Article 30 of the Constitution. | Recognized that AMU was established by the Muslim community, and statutory incorporation does not negate its minority status, thereby affirming its rights under Article 30. |

| Interpretation of ‘Establishment’ | Interpreted ‘establishment’ strictly, focusing on the legal act of creation by Parliament, disregarding the role of the Muslim community in founding the institution. | Adopted a broader interpretation, acknowledging the foundational role of the Muslim community in establishing AMU, despite its statutory incorporation. |

| Interpretation of ‘Administration’ | Limited the scope of ‘administration’ rights for minority institutions, allowing significant state intervention and regulation. | Affirmed the autonomy of minority institutions in administration, subject to reasonable regulations, emphasizing the protection of minority rights. |

Impact on Other Minority Institutions

- Potential for Re-evaluation of Minority Status Claims

- The 2024 ruling sets a precedent that may prompt other educational institutions established by minority communities to seek recognition of their minority status, even if they were incorporated by statutory means.

- Institutions previously denied minority status based on the 1967 judgment might now have grounds to re-evaluate and potentially reclaim their status under Article 30.

- Encouragement for Minority Community Initiatives

- The affirmation of minority rights in establishing and administering educational institutions may encourage minority communities to initiate and manage their own educational establishments, fostering diversity in the educational landscape.

Broader Legal Implications

- Shifts in Judicial Approach to Minority Rights

- The 2024 judgment reflects a more inclusive and expansive interpretation of minority rights under the Constitution, moving away from the restrictive interpretations of the past.

- It underscores the judiciary’s role in protecting the rights of minority communities, ensuring their ability to preserve their culture, language, and religion through educational institutions.

- Clarification of Constitutional Provisions

- The ruling provides clarity on the interpretation of ‘establishment’ and ‘administration’ in Article 30, offering a more nuanced understanding that balances minority rights with state interests.

- Influence on Future Judicial Decisions

- This landmark judgment is likely to influence future judicial decisions concerning minority rights and educational institutions, serving as a reference point for interpreting constitutional provisions related to minority protections.

State Regulation and Minority Institutions

Scope of State Intervention

- Balancing Autonomy with Regulatory Oversight

- Constitutional Framework

- Article 30(1) of the Indian Constitution grants religious and linguistic minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

- This provision aims to preserve the cultural and educational rights of minorities, ensuring their distinct identity within the pluralistic fabric of India.

- State’s Role in Regulation

- While minority institutions enjoy autonomy, the state holds the responsibility to ensure that educational standards are maintained across all institutions.

- Regulatory measures may include setting academic standards, ensuring financial transparency, and enforcing adherence to national educational objectives.

- Judicial Interpretation

- The Supreme Court of India has consistently upheld that the right to administer does not equate to the right to maladminister.

- Reasonable regulations that promote academic excellence and prevent maladministration are permissible and do not infringe upon the rights conferred by Article 30.

- Constitutional Framework

Recent Supreme Court Stance

- Upholding the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004

- Background

- The Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, was enacted to provide a structured framework for madarsa education in the state.

- The Act aimed to integrate madarsas into the broader educational system while preserving their unique religious and cultural teachings.

- Allahabad High Court Ruling

- In March 2024, the Allahabad High Court declared the Act unconstitutional, stating that it violated the principle of secularism enshrined in the Constitution.

- The court directed the state government to accommodate madarsa students in formal schooling systems.

- Supreme Court’s Reversal

- In November 2024, the Supreme Court overturned the High Court’s decision, upholding the constitutional validity of the Act.

- The apex court emphasized that the Act was consistent with the state’s obligation to provide adequate education for children and did not violate the principle of secularism.

- Background

Analysis of the Court’s Reasoning

- Secularism and State Facilitation of Education

- Defining Secularism

- In the Indian context, secularism implies equal treatment of all religions by the state, without favoring or discriminating against any.

- The state is mandated to ensure that religious freedoms are protected while maintaining a neutral stance in religious matters.

- State’s Educational Mandate

- The Constitution obligates the state to provide free and compulsory education to all children up to the age of 14 years.

- This duty encompasses ensuring that educational institutions, including those run by minority communities, adhere to certain standards to provide quality education.

- Court’s Interpretation

- The Supreme Court held that the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, facilitated the state’s educational mandate without infringing upon the secular character of the Constitution.

- The Act was viewed as a means to integrate madarsa education into the mainstream educational framework, ensuring that students receive both religious and secular education.

- Defining Secularism

Implications for Minority Institutions

- Compliance with State Regulations

- Adherence to Educational Standards

- Minority institutions are required to comply with state-imposed regulations that aim to maintain educational standards and promote academic excellence.

- This includes following prescribed curricula, employing qualified teachers, and ensuring infrastructural adequacy.

- Financial Transparency

- Institutions must maintain transparent financial practices, including proper accounting and utilization of funds, especially when receiving state aid.

- Financial audits and disclosures may be mandated to ensure accountability.

- Adherence to Educational Standards

- Preservation of Minority Character

- Autonomy in Administration

- While complying with state regulations, minority institutions retain the right to administer their affairs, including admissions, appointments, and governance, in a manner that preserves their unique cultural and religious identity.

- This autonomy is protected under Article 30, provided it does not conflict with the broader objectives of national education policies.

- Cultural and Religious Education

- Minority institutions can continue to impart education that reflects their cultural and religious ethos, alongside the secular curriculum mandated by the state.

- This dual approach ensures that students receive a holistic education that respects their heritage while equipping them for broader societal integration.

- Autonomy in Administration

Minority Institutions and Secularism

Defining Secularism in the Indian Context

- Constitutional Principles

- Preamble Inclusion

- The term ‘secular’ was incorporated into the Preamble of the Indian Constitution through the 42nd Amendment Act of 1976, affirming India’s commitment to a state that does not favor any religion.

- Fundamental Rights

- Article 25 guarantees all individuals the freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, subject to public order, morality, and health.

- Article 26 allows religious denominations to manage their own affairs in matters of religion, establish institutions, and own property.

- Article 30 provides minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice, ensuring the preservation of their culture and language.

- Preamble Inclusion

- Judicial Interpretations

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973)

- The Supreme Court recognized secularism as a part of the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution, meaning it cannot be altered or abrogated by any amendment.

- S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994)

- The Court elaborated that secularism entails treating all religions equally and that the state must maintain a principled distance from all religions, neither favoring nor discriminating against any.

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973)

Tension Between Secularism and Minority Rights

- State Funding and Religious Education

- State Funding

- Minority institutions often receive government aid to ensure educational standards and accessibility.

- The challenge lies in ensuring that such funding does not lead to state interference in the religious aspects of these institutions.

- Religious Education

- Minority institutions aim to impart education that aligns with their cultural and religious values.

- Balancing religious instruction with the secular curriculum mandated by the state can lead to conflicts, especially when state regulations are perceived as infringing upon religious teachings.

- State Funding

- Autonomy Versus State Control

- Autonomy

- Under Article 30, minority institutions have the right to administer their affairs, including admissions, appointments, and curriculum design, to preserve their unique identity.

- State Control

- The state has a legitimate interest in ensuring that all educational institutions adhere to certain standards, including infrastructure, faculty qualifications, and academic performance.

- Regulations are often implemented to maintain these standards, but they must not infringe upon the rights guaranteed under Article 30.

- Autonomy

Comparison of Autonomy and State Control in Minority Institutions

| Aspect | Autonomy | State Control |

|---|---|---|

| Admissions | Minority institutions can set their own admission criteria. | State may impose quotas or reservations to ensure diversity and inclusion. |

| Curriculum Design | Institutions can incorporate religious teachings alongside secular subjects. | State mandates adherence to national educational standards and curricula. |

| Faculty Appointments | Freedom to appoint staff aligned with the institution’s values. | State may require certain qualifications or certifications for faculty. |

| Financial Management | Autonomy in managing funds and resources. | State audits and regulations to ensure transparency and proper utilization. |

Case Studies: Analysis of Recent Supreme Court Judgments Affecting Minority Institutions

- T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka (2002)

- Background

- The case addressed the extent of state regulation permissible over minority educational institutions, focusing on admissions, fee structures, and administrative autonomy.

- Judgment

- The Supreme Court held that while minority institutions have the right to establish and administer their institutions, this right is not absolute.

- The state can impose reasonable regulations to ensure educational standards and prevent maladministration, provided these do not dilute the minority character of the institution.

- Background

- Islamic Academy of Education v. State of Karnataka (2003)

- Background

- Following the T.M.A. Pai judgment, there was ambiguity regarding the extent of state control over admissions and fee structures in minority institutions.

- Judgment

- The Court clarified that while minority institutions can admit students of their choice, they must adhere to state-imposed regulations aimed at maintaining academic standards.

- It also upheld the state’s right to set up committees to monitor admissions and fee structures to prevent profiteering and ensure merit-based admissions.

- Background

- P.A. Inamdar v. State of Maharashtra (2005)

- Background

- The case revisited the issues of admissions and fee regulation in minority institutions, especially in the context of professional courses.

- Judgment

- The Supreme Court ruled that minority institutions have the right to admit students of their choice and set reasonable fee structures.

- However, the state can intervene to prevent capitation fees and profiteering, ensuring that the fees charged are not exorbitant and are used for the institution’s development.

- Background

Educational Standards and Minority Institutions

Role of Minority Institutions in Maintaining Educational Quality

- Contributions to Higher Education:

- Diverse Academic Offerings: Minority institutions provide a range of programs, enriching India’s educational landscape.

- Cultural Preservation: They integrate cultural and linguistic heritage into curricula, fostering inclusivity.

- Notable Examples:

- Aligarh Muslim University (AMU): Established in 1875, AMU offers programs in sciences, humanities, and professional fields.

- St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai: Founded in 1869, it emphasizes liberal arts and sciences.

- Challenges Faced:

- Resource Constraints: Limited funding affects infrastructure and faculty recruitment.

- Regulatory Pressures: Balancing autonomy with compliance to state regulations poses challenges.

- Quality Assurance: Ensuring consistent educational standards amidst diverse curricula is complex.

State’s Role in Ensuring Standards

- Regulatory Frameworks:

- University Grants Commission (UGC): Established in 1956, UGC sets standards for higher education institutions.

- National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC): Founded in 1994, NAAC assesses and accredits institutions to ensure quality.

- Quality Assurance Mechanisms:

- Periodic Evaluations: Regular assessments monitor adherence to educational standards.

- Funding Incentives: Financial support is linked to compliance with quality benchmarks.

- Curriculum Guidelines: Recommendations ensure alignment with national educational objectives.

Impact of Supreme Court Rulings

- Autonomy in Curriculum Design:

- T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka (2002): Affirmed minority institutions’ rights to manage affairs, including curriculum choices.

- Islamic Academy of Education v. State of Karnataka (2003): Clarified that while institutions have autonomy, they must adhere to national standards.

- Compliance with National Standards:

- Balancing Autonomy and Regulation: Institutions can design curricula but must meet quality benchmarks set by bodies like UGC.

- Ensuring Educational Quality: Supreme Court emphasizes that autonomy should not compromise educational standards.

Key Judicial Pronouncements Shaping Minority Rights

| Case Name | Year | Key Issue Addressed | Supreme Court’s Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. Azeez Basha v. Union of India | 1967 | Minority status of Aligarh Muslim University | Denied AMU’s minority status, stating it was established by an Act of Parliament |

| T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka | 2002 | Rights of minority institutions in administration and admissions | Affirmed rights to establish and administer institutions, subject to reasonable state regulations |

| Islamic Academy of Education v. State of Karnataka | 2003 | Clarification on admissions and fee structures in minority institutions | Allowed state regulation to ensure transparency and prevent profiteering |

Socio-Political Implications of the 2024 Ruling

Reactions from Political Entities

- Government Responses:

- Union Government: The central administration acknowledged the Supreme Court’s decision, emphasizing its commitment to uphold constitutional provisions concerning minority rights.

- State Governments: States with significant minority populations, such as Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, expressed support for the ruling, highlighting its potential to enhance educational opportunities for minority communities.

- Opposition Viewpoints:

- Major Opposition Parties: Political entities like the Indian National Congress and the All India Trinamool Congress welcomed the verdict, viewing it as a reinforcement of secular principles and minority rights.

- Regional Parties: Parties such as the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu and the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) in Telangana expressed approval, citing the ruling’s alignment with their advocacy for educational autonomy and minority welfare.

Public Discourse and Media Analysis

- Debates on Minority Rights:

- Academic Circles: Scholars and educators engaged in discussions about the ruling’s implications for minority institutions’ autonomy and the broader landscape of educational rights in India.

- Civil Society Organizations: Groups advocating for minority rights viewed the decision as a positive step toward safeguarding the interests of religious and linguistic minorities.

- Secularism and Education:

- Media Outlets: Leading newspapers and news channels analyzed the ruling’s impact on the secular fabric of the nation, debating how it balances state intervention with minority institutions’ autonomy.

- Public Opinion: Social media platforms witnessed diverse viewpoints, with some individuals expressing concerns about potential preferential treatment, while others emphasized the importance of preserving minority cultural and educational identities.

Potential Impact on Upcoming Policies

- Educational Reforms:

- Curriculum Development: The ruling may prompt educational authorities to consider more inclusive curricula that reflect the diverse cultural backgrounds of minority communities.

- Institutional Autonomy: There could be a reevaluation of policies to grant greater administrative and academic freedom to minority-run educational institutions.

- Minority Welfare Schemes:

- Scholarship Programs: The government might introduce or expand scholarship initiatives aimed at supporting students from minority communities in pursuing higher education.

- Infrastructure Development: Investments in the infrastructure of minority educational institutions could be prioritized to enhance their capacity and quality of education.

Future of Minority Institutions Post-2024 Ruling

Prospects for Minority Institutions

- Opportunities for Expansion:

- Increased Autonomy: The 2024 Supreme Court ruling potentially grants minority institutions greater self-governance, enabling them to tailor educational programs to their community’s cultural and linguistic needs.

- Enhanced Funding: With reaffirmed minority status, these institutions may access specific government grants and international funding aimed at promoting educational diversity.

- Curriculum Development: Institutions can design curricula that incorporate their community’s heritage, fostering a more inclusive educational environment.

- Challenges in Administration:

- Regulatory Compliance: Balancing autonomy with adherence to national educational standards may present administrative complexities.

- Resource Allocation: Ensuring equitable distribution of resources while maintaining the institution’s minority character could be challenging.

- Political Pressures: Navigating political dynamics to safeguard minority rights without compromising institutional integrity requires strategic leadership.

Legal Avenues for Other Institutions

- Potential for Seeking Minority Status:

- Precedent Utilization: The ruling sets a legal precedent, encouraging other institutions to pursue minority status by demonstrating their establishment and administration by minority communities.

- Judicial Recourse: Institutions may file petitions in higher courts, citing the 2024 judgment to assert their minority rights.

- Anticipated Legal Challenges:

- Burden of Proof: Institutions must provide substantial evidence of their minority character, including historical documentation and community support.

- State Opposition: Some state governments may contest these claims, leading to prolonged legal battles.

- Policy Ambiguities: Inconsistencies in state and central policies regarding minority status could result in legal complexities.

Role of Civil Society and Advocacy Groups

- Support for Minority Rights:

- Awareness Campaigns: Organizations can educate communities about their rights and the implications of the ruling, empowering them to seek minority status.

- Legal Assistance: Providing legal aid to institutions pursuing minority recognition ensures informed and effective advocacy.

- Engagement with Policy-Making:

- Consultative Participation: Advocacy groups can collaborate with policymakers to draft regulations that balance minority rights with educational standards.

- Monitoring Implementation: Ensuring that the ruling’s provisions are effectively enacted at the grassroots level safeguards minority interests.

Conclusion: Synthesis and Critical Reflection

Summarization of Key Findings

- Legal Developments:

- The 2024 Supreme Court ruling has redefined the criteria for minority educational institutions, emphasizing the rights of minorities to establish and administer their own institutions.

- This decision overturns previous judgments, notably the 1967 verdict, thereby altering the legal landscape for minority rights in education.

- Socio-Political Impacts:

- The ruling has sparked diverse reactions from political entities, with some viewing it as a reinforcement of minority rights, while others express concerns about its implications for national unity.

- Public discourse has intensified, focusing on the balance between secularism and the preservation of minority identities within the educational sector.

Critical Analysis of the Supreme Court’s Approach

- Consistency in Judicial Reasoning:

- The Court’s approach reflects a shift towards a more inclusive interpretation of minority rights, aligning with evolving societal values.

- However, this shift raises questions about the consistency of judicial reasoning, given the departure from earlier precedents.

- Alignment with Constitutional Principles:

- The ruling underscores the importance of Articles 29 and 30 of the Indian Constitution, which protect the rights of minorities to conserve their culture and establish educational institutions.

- By reaffirming these rights, the Court aims to uphold the constitutional commitment to diversity and pluralism.

Future Outlook

- Evolving Landscape of Minority Rights in India’s Educational Sector:

- The ruling is likely to encourage other minority communities to seek similar recognition for their educational institutions, potentially leading to a more diverse educational environment.

- It also presents challenges in ensuring that the autonomy granted to minority institutions does not conflict with national educational standards and objectives.

The 2024 Supreme Court ruling marks a significant milestone in the interpretation of minority rights within India’s educational framework. While it offers opportunities for minority communities to assert their educational autonomy, it also necessitates careful consideration of the broader implications for national cohesion and educational quality.

Practice Question

Critically analyze the implications of the 2024 Supreme Court ruling on the minority status of educational institutions in India, focusing on socio-political impacts, legal precedents, and future challenges. (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.