Pesticide usage in India – Issues and Solutions

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

The government’s recent proposal to ban 27 pesticides in India has garnered both support and opposition from various segments of the society. It is being welcomed by several exporters (like spice exporters) and is seen as a long-pending implementation of the Anupam Verma Committee recommendations. On the other hand, pesticide manufacturers are threatening to take the government to the court over this move. This proposal is significant given the danger to farmers’ income posed by invading pests like the fall army worm and more recently, locusts.

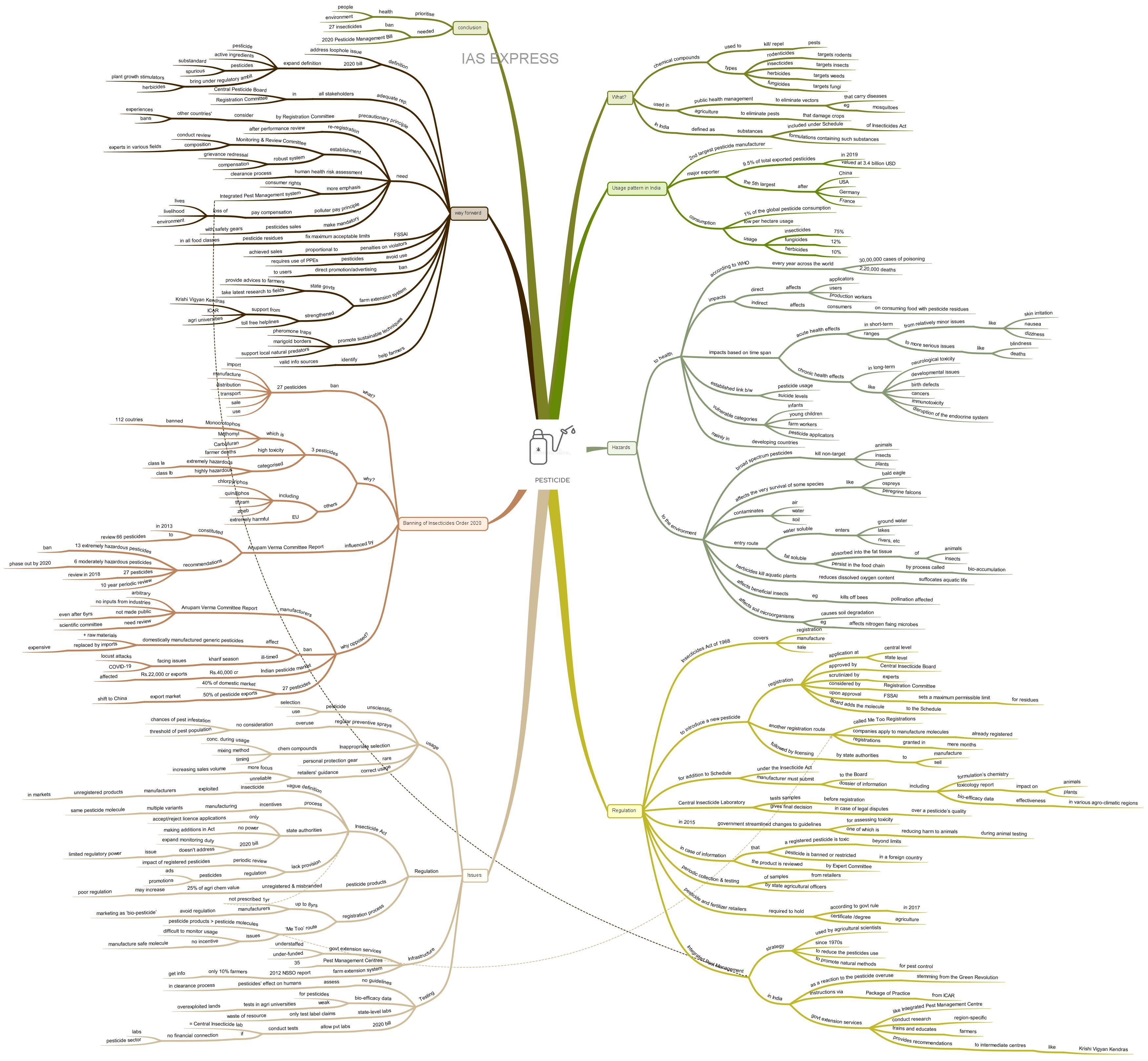

What are pesticides?

- Chemical compounds that are employed to eliminate pest organisms are called pesticides. These are used to kill or repel pests like rodents (rodenticides), insects (insecticides), weeds (herbicides) and fungi (fungicides).

- They are used in public health management to eliminate disease carrying vectors like mosquitoes.

- They are used in agriculture to eliminate pests that damage crop plants.

- According to the Insecticide Act, insecticides are substances that are included under its Schedule or preparations that include such substances.

What is the usage pattern in India?

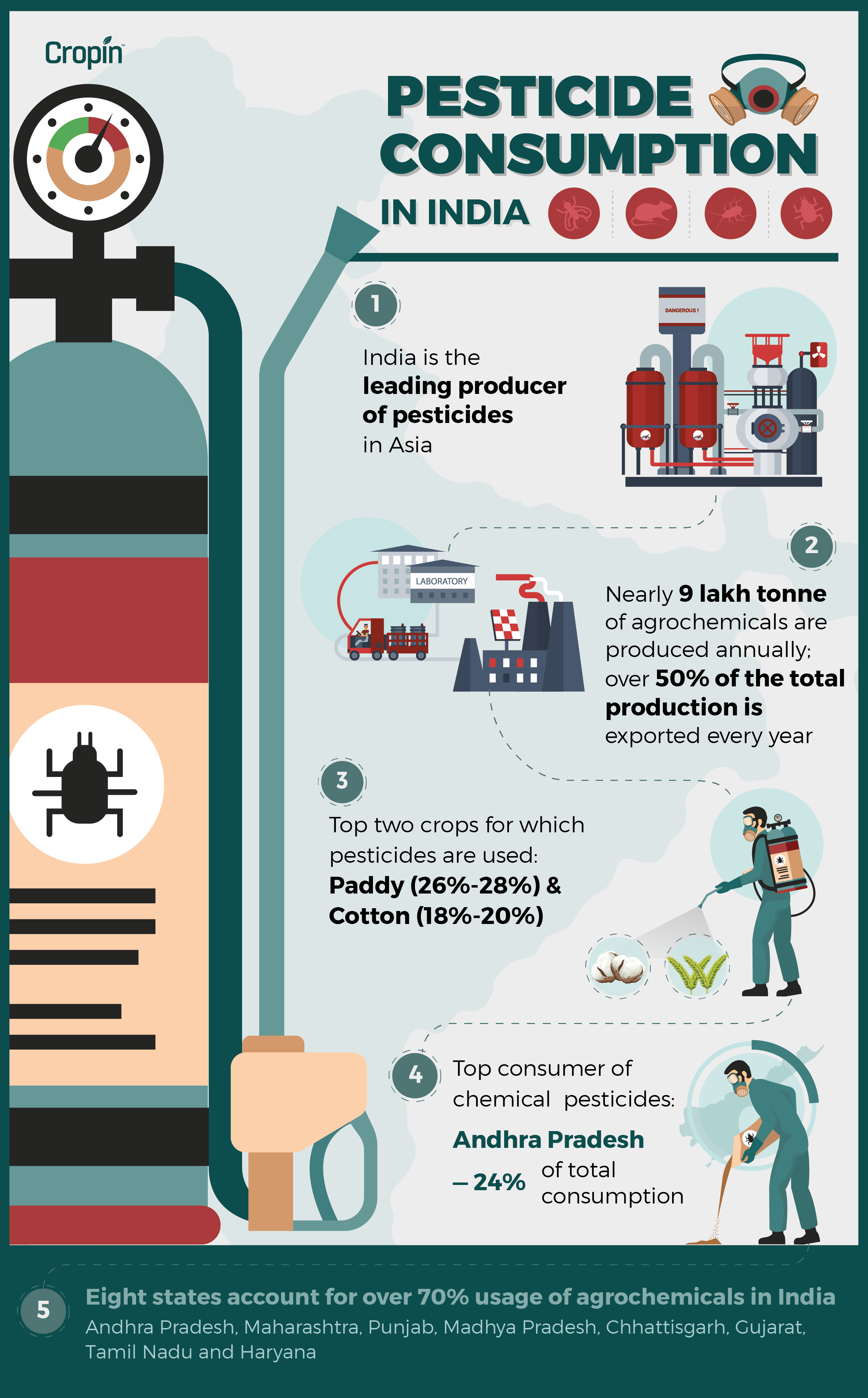

- India is the 2nd largest pesticide manufacturer in the world. It is also a major exporter- accounting for 5% (valued at 3.4 billion USD) of the total exported pesticides in 2019- making it the 5th largest exporter after China, USA, Germany and France.

- However India accounts only for 1% of the global pesticide consumption.

- Insecticides form the largest portion of pesticide consumption in India (at 75%) followed by fungicide at 12% and herbicides at 10%.

- Though the ‘per hectare usage’ is relatively low compared to rest of the countries, indiscriminate use (in terms of quantity and timing) is still an issue.

What are the hazards posed by pesticides?

- Pesticides pose threat not only to human and animal health but also to the environment.

To health

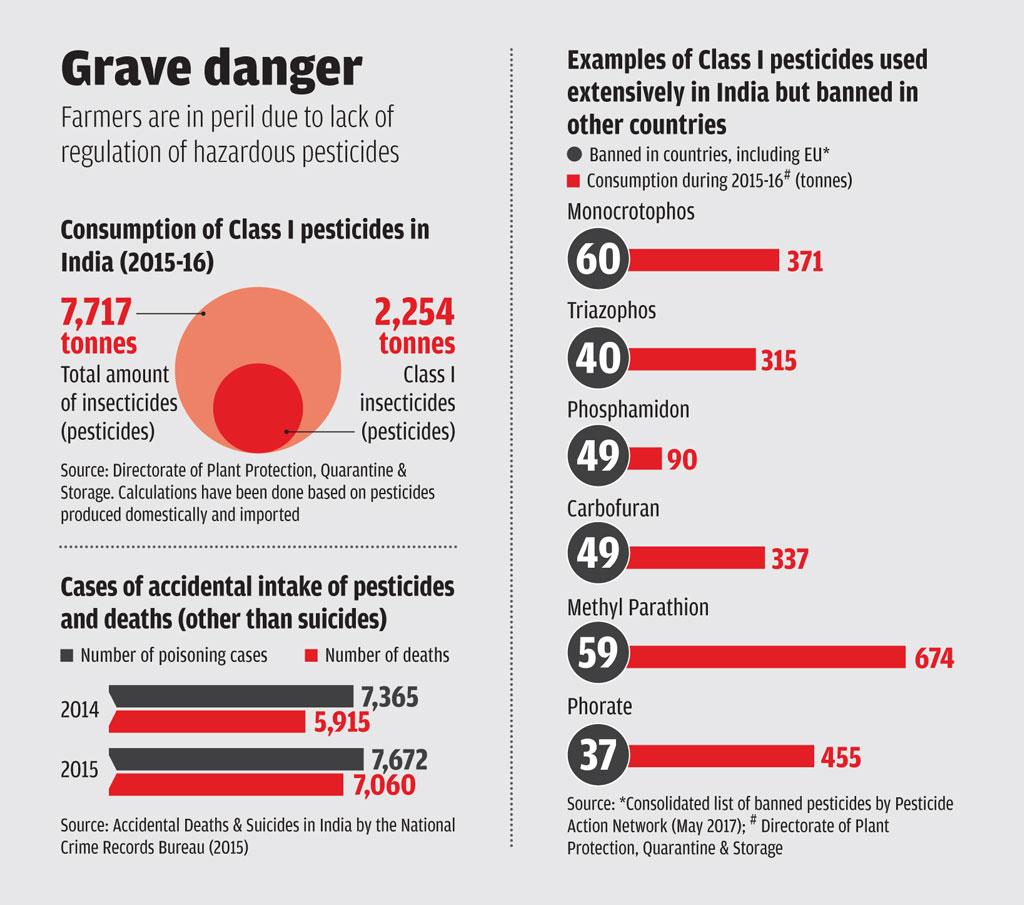

- According to WHO, pesticides are the cause of 30,00,000 cases of poisoning and 2,20,000 deaths every year across the world. This has been increasing over the years.

- The health impact can be:

- Direct– affecting applicators, users and production workers

- Indirect– affecting the consumers when they eat food with pesticide residues

- The time span of the impacts can be:

- Short term or acute health effects– causing relatively minor issues like skin irritation, dizziness and nausea to more serious issues like blindness and even death.

- Long term or chronic health effects– like neurological toxicity, developmental issues, birth defects, cancers, immunotoxicity and disruption of the endocrine system.

- Some studies have established a link between pesticide usage and suicide

- Certain categories of the population are more vulnerable to such effects- infants, young children, farm workers and pesticide applicators.

- Majority of the human health impacts of pesticide use is reported from developing countries.

To the environment

- Broad spectrum pesticides can kill non-target animals, insects and plants.

- The overuse has threatened the very survival of certain species like the bald eagle, ospreys and peregrine falcons.

- The pesticides also contaminate air, water and soil.

- Pesticides enter the ecosystem via 2 routes:

- Water-soluble pesticides dissolve in water and enter water bodies like ground water, lakes, rivers, etc. to affect unintended target animals.

- Fat-soluble pesticides get absorbed into the fat tissue of animals and persist in the food chain by a process called bio-amplification.

- When herbicides kill off aquatic plants, the dissolved oxygen content of the water bodies decrease and causes suffocation among the aquatic life forms.

- The effect of pesticides on beneficial insects is a major cause of concern. The overuse of pesticides is one of the major causes of the world-wide decline in honeybee population- affecting the pollination process that is vital for the agricultural sector.

- Pesticides also affect soil microorganisms and consequently, lead to soil degradation. eg: certain pesticides are known to impede the nitrogen fixing function of soil bacteria.

How is pesticide usage regulated in India?

- The Insecticides Act of 1968 covers the registration, manufacture and sale of pesticides in India.

- In order to introduce a new pesticide into the market, the firms have to make application at the state and central levels. New pesticides are approved by the Central Insecticide Board.

- To add the new pesticide molecule to the Schedule of Insecticides Act, the manufacturer is to submit a dossier of information to the Board. These include:

- The formulation’s chemistry

- Toxicology report with details on its impact on animals and plants

- Bio-efficacy data- on how effective the molecule is on crops grown in various agro-climatic regions.

- The Central Insecticide Laboratory can test the pesticide samples before registration. Its decision are final in case of legal disputes over a pesticide’s quality.

- It is scrutinized by experts and considered by the Registration Committee. If the committee approves it, the FSSAI (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India) sets a maximum permissible limit for residues. Followed by this, the Board adds the molecule to the Schedule.

- After incorporation into the Act, the pesticide companies can apply for manufacturing the molecule.

- ‘Me Too’ Registrations: this is another option for registration where the companies apply to manufacture molecules that are already registered. These registrations are granted in a matter of months.

- After the registration, the firms must get its license from the state authorities to manufacture or sell it.

- The government streamlined changes to guidelines for testing the pesticides’ toxicity in 2015. One of these changes was introduced to reduce the harm done to animals during testing.

- When information about toxic effects of any registered pesticide comes into light or when a pesticide is banned or restricted in a foreign country, an Expert Committee reviews the pesticide’s impact.

- The state authorities (agricultural officers) are required to periodically collect and test samples of pesticides from retailers.

- In 2017, the government mandated that pesticide and fertilizer retailers must hold a certificate or a degree in agriculture.

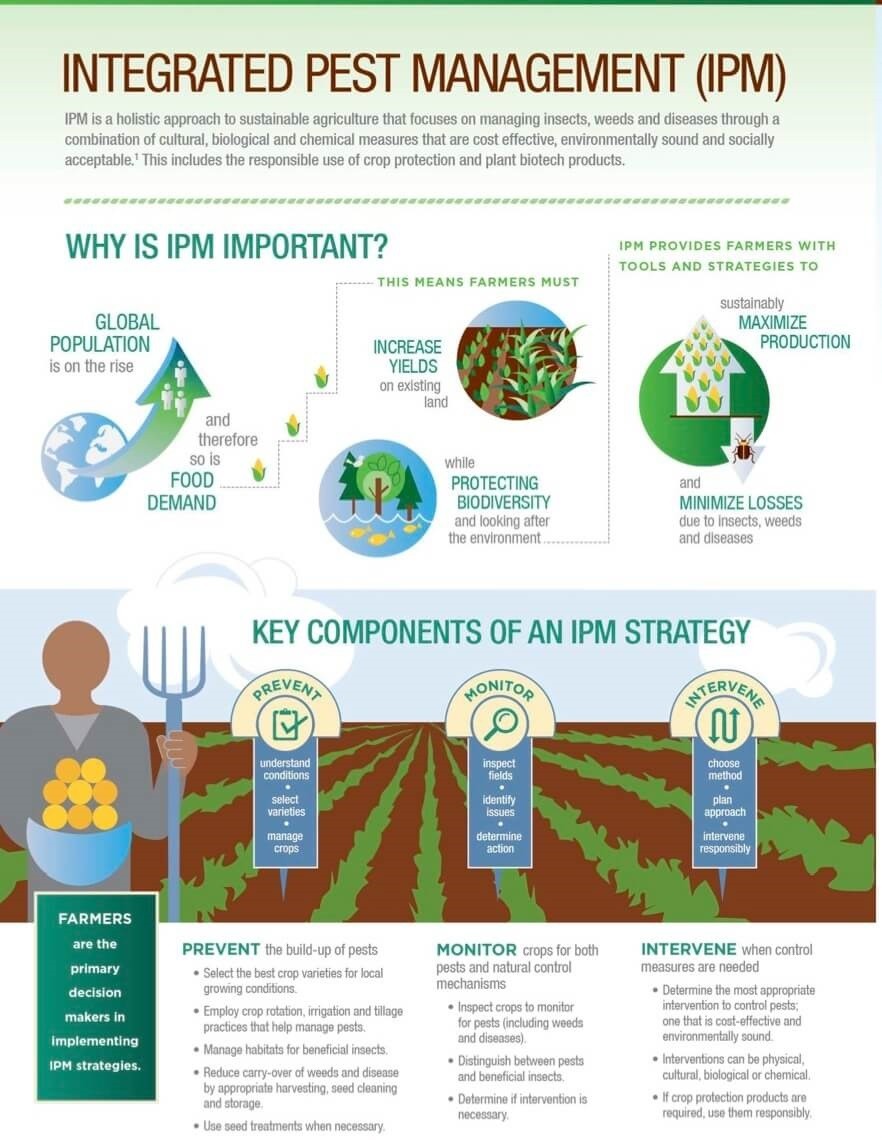

Integrated Pest Management

- It is a strategy used by agricultural scientists since the 1970s to reduce the use of pesticides.

- In India, it came into use as a reaction to the pesticide overuse in connection with the Green Revolution.

- Under IPM, farmers are advised to go for more natural methods of pest control.

- Institutions like the ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) provides instructions via booklets called “Package of Practice”.

- Government extension services like the Integrated Pest Management Centre conduct research that are region-specific, trains and educates the farmers and provides recommendations to intermediate centres like the Krishi Vigyan Kendras.

What are the issues?

On the usage side

- Prevalence of unscientific practices in terms of pesticide selection and use– even in the states with better literacy like Kerala.

- Farmers commonly use regular preventive sprays without taking into account the chances of pest infestation or threshold of pest population. This leads to overuse.

- Inappropriate selection in usage- in terms of the chemical compound, its concentration for use as spray fluid, mixing method and timing.

- Use of appropriate personal protection gear is rare.

- Reliance on retailers for usage guidance. These retailers are often unaware of the correct usage method and are driven by desire for increasing sales volume.

On the regulation side

- The vague definition under the Insecticide Act is one of the largest regulatory gaps. The loophole is exploited by manufacturers of products like herbicides and plant growth stimulators to inundate the markets with unregistered products. This was the case discovered during the investigations into farmer deaths in Maharashtra.

- The process used under the Insecticide Act has encouraged the manufacturing of multiple variants of the same pesticide molecule. According to a 2016 Parliamentary Standing Committee Report, 2.5 lakh pesticide products were cleared, though only 28 pesticide molecules had been registered.

- According a 2015 report, spurious, unregistered and misbranded pesticide products account for 25% of the agrochemical industry’s value. This portion is expected to increase over the years in the absence of proper regulation which itself becomes increasingly difficult with more and more products entering the market.

- The registration process may stretch up to 8 years (instead of the 1 year prescribed by the Act). This process is taxing on the manufacturers. Hence, many choose to avoid the regulation process altogether by marketing their product as ‘bio-pesticide’.

- The ‘Me Too’ registration route is the reason why there are far more pesticide products than pesticide molecules in India. this route creates 2 problems:

- Since it’s easier to manufacture an already registered molecule as a new product instead of manufacturing an entirely new molecule, there is low incentive for manufacturers to come up with safer novel molecules.

- The volume of such products entering the market makes it difficult for the state government to monitor their usage.

- Under the Insecticide Act, the state authorities can only accept or reject license applications. They do not have other powers like making additions to the Act. This limits their role as a regulator. The 2020 bill seeks to expand the monitoring duties of the state authorities but does not address this limited regulatory power

- Lack of provisions for periodic review of the impact of registered pesticides. Once registered, these incompletely tested products are valid for use for perpetuity.

- There is no regulation of the pesticides’ advertising and promotion via dealers. Even the recently introduced 2020 Pesticide Management Bill is silent on this issue.

On infrastructure side

- Government extension services are understaffed and under-funded.

- There are far too few Integrated Pest Management Centres- only 35 across India.

- Collapse of the farm extension system. A 2012 NSSO report showed that only 10% of farmers got their information from it.

On testing side

- The government is yet to give guidelines for assessing the pesticides’ effect on humans for the market introduction clearance. This implies that these products are being sold in the market without any idea of its impacts on users.

- The bio-efficacy data collected for the pesticides is weak as these tests are conducted at agricultural universities where the lands used for testing are being overexploited for years.

- The state-level labs can only test the label claims of the products i.e. proportions of the active ingredients. This is especially wasteful of resources because, while the Central Insecticide laboratory has 1,600 tests per year testing target, the state labs can test 68,000 samples per year.

- The 2020 bill seeks to allow private labs to conduct all tests as the Central Insecticide Lab- as long as there is no financial connection between these labs and the pesticide sector. However, this provision is attracting mixed reactions.

What is the Banning of Insecticides Order 2020?

- In May, the Agriculture Ministry put out a draft notification that sought to ban 27 pesticides in terms of its import, manufacture, sale, transport, distribution and use.

- These pesticides include Acephate, Atrazine, Benfuracarb, Butachlor, Captan, Carbofuran, Chlorpyriphos, 2,4-D, Deltamethrin, Monocrotophos, Methomyl, etc.

- Malathion, which is currently being used to control the locust attack, is one of these 27 pesticides.

Why are these pesticides being banned?

- 3 of these pesticides- namely, Monocrotophos, Methomyl and Carbofuran are associated with high toxicity. They have been the cause of farmer deaths in the recent past.

- They are categorized as extremely hazardous (class Ia) or highly hazardous (class Ib) by the WHO.

- Monocrotophos is banned in 112 countries including China and Pakistan. It is behind the farmer deaths in 2017 in Vidharbha in Maharashtra.

- Some of the others in the list- such as chlorpyriphos, quinalphos, thiram and zineb– are considered as ‘extremely harmful’ by the European Union.

- Between 1970 and 2015, India had banned 34 insecticide products, withdrawn 7 and restricted the use of 13.

Anupam Verma Committee Report

- The report from the 2015 committee headed by Anupam Verma, an IARI professor, is a major influence in the current proposal for banning the 27 pesticides.

- It was constituted in 2013 to review 66 pesticides which have been either banned or restricted for use in other countries.

- It recommended the following;

- 13 extremely hazardous pesticides to be banned

- 6 moderately hazardous pesticides to be phased out by 2020

- 27 pesticides to be reviewed in 2018

- A 10 year periodic review of pesticides

- It is these 27 pesticides that the Agriculture Ministry seeks to ban through this order.

- Already in 2018, 18 pesticides were banned by a government order. Seven of these are class I pesticides.

Why is the order being opposed?

- Manufacturers have criticized the Anupam Verma Committee Report as being arbitrary and as having been created without taking inputs from any of the industry’s players.

- The manufacturers have also pointed out that the report hasn’t been made public even after 6 years.

- They have called for a review of the report by a scientific committee.

- There are concerns that this ban will affect the domestically manufactured generic pesticides and their raw materials. There are also fears that these generic products would be replaced with imported pesticides that could be more expensive.

- The Indian pesticide market is worth 40,000 crore INR. Of this, 22,000 crore INR worth of products are exported to the global market. These exports could take a hit.

- These 27 pesticides account for 40% of the domestic market and 50% of the pesticide exports. The export market of these products (worth 12,000 crore INR) will shift to China- already the global leader in the pesticide sector.

- There are also concerns as the upcoming kharif season is already facing threat from the locust attacks apart from setback brought in by the Great Lockdown.

- It is not only the industrial players that are opposing this move, but also the Chemicals and Fertilizer Ministry which said that the move is ill-timed in light of the COVID-19

What is the way forward?

- The loophole presented by the definition is to be addressed. For comparison, USA’s definition- ‘any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling or mitigating any pest or intended for use as a plant regulator, defoliant or desiccant, or any nitrogen stabiliser’. USA is the largest pesticide market in the world accounting for 18% of the consumption worldwide.

- This is one of the issues that the 2020 Pesticide Management Bill seeks to address. It expands the definition of not only pesticides but also active ingredients, substandard and spurious pesticides. Notably, it will bring products like plant growth stimulators and herbicides within the regulatory ambit.

- Adequate representation of all the stakeholders in the Central Pesticide Board and the Registration Committee.

- Use of ‘precautionary principle’– the Registration Committee should be allowed to take into account experiences of other countries with the pesticides under review. A pesticide being banned in multiple countries could serve as a basis for its restriction or even ban in India.

- Grant of registration should not be indefinite. Need to bring in the practice of re-registration after proper performance review.

- Need to establish an independent Monitoring & Review Committee, composed of experts from various sectors like toxicology, animal husbandry, public health, etc., to conduct review studies.

- There is a need to introduce the much-needed human health risk assessment component in the clearance of new pesticides. The toxicology tests required by the regulator must be made more comprehensive. For comparison, up to 70 toxicology tests could be required by the regulators depending upon the product’s intended use. This covers the assessment of impacts on people, animals and environment.

- FSSAI could fix maximum acceptable limits for pesticide residues in all classes of food.

- More attention must be paid to consumer rights in this issue.

- Need to establish a robust system for grievance redressal and compensation. The penalties imposed on violators must be in proportion to the sales achieved.

- Use of polluter pay principle for paying compensation for losses of human or animal lives, livelihood and environment.

- The government can mandate the pesticide companies to market their products with necessary safety gears of appropriate quality.

- The FAO and WHO, in the international code of conduct on pesticide management, recommended avoiding the use of pesticides that require the use of PPEs that are uncomfortable/expensive.

- Pesticides must be regulated like drugs– i.e. cannot be advertised/ promoted directly to the users. This is because proper regulation of advertising and promotion of these toxic compounds can address their overuse and misuse. The pesticide companies’ representatives should not be the last point of contact to the farmers.

- Instead of roping in retailers and the pesticide sector to compensate for the government extension service, focus must be on leveraging the farm extension system. State government employees can be roped in to provide vital advice to the farmers and take the latest research to the fields.

- The extension system can be strengthened with support from Krishi Vigyan Kendras, ICAR and other agricultural universities, toll-free helpline system, etc.

- As internet connectivity deepens, more and more farmers will depend on the internet for accessing information on pesticides. Public policy must be aimed at helping them identify valid information sources and protect them from spurious information put forth by profit-driven firms to promote their sales.

- Though Integrated Pest Management system is largely inefficient in India, it needs to be focused on. There is a need to promote sustainable techniques like pheromone traps, marigold borders, supporting local population of the pests’ natural predators (like birds), etc.

Conclusion

The Insecticide Act was introduced in a period when boosting food production was the major priority. India is now is an era of agricultural surplus. Ensuring the health of people and environment must be the major priority now. The current proposal to ban the 27 insecticides and the 2020 Pesticide Management Bill are steps in the right direction.

Practice Question for Mains

Comment on the government’s recent decision to ban certain pesticides. Examine the difficulties in eliminating the use of toxic pesticides. (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.

instead of giving such a lengthy article,make it crisp, mains ready answer