Rukhmabai (1864 –1955): Important Personalities of Modern India

Prelims Sureshots » Important Personalities of Modern India

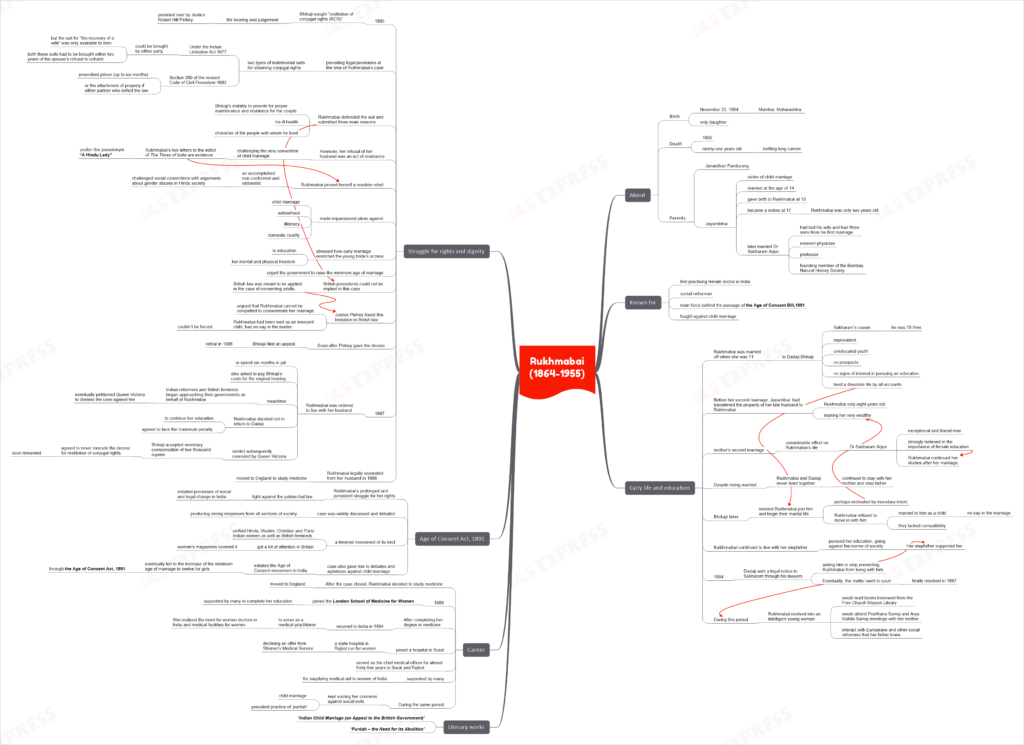

Rukhmabai (1864-1955) was the first practising female doctor in India. She was the main force behind the passage of the Age of Consent Bill,1891. She fought against child marriage and has her name listed as one of the renowned faces bringing about social reforms in India.

Early life and education

- Rukhmabai Bhimrao Raut was born on November 22, 1864, in Mumbai, Maharashtra.

- She was the only daughter of Janardhan Pandurang and Jayantibhai.

- Rukhmabai’s mother was a victim of child marriage. She was married at the age of 14 and gave birth to Rukhmabai at 15, and became a widow at 17 when Rukhmabai was only two years old.

- Her mother later married Dr Sakharam Arjun who had lost his wife and had three sons from his first marriage. He was an eminent physician, professor and founding member of the Bombay Natural History Society.

- Adhering to prevailing customs and social pressure, Rukhmabai was married off when she was 11 to Dadaji Bhikaji, who was Sakharam’s cousin and was 19 then.

- Before her second marriage, Jayantibai transferred the property she had inherited from her late husband to Rukhmabai when the latter was only eight years old, making her very wealthy in her own right.

- Her mother’s second marriage had a considerable effect on Rukhmabai’s life. Dr Sakharam Arjun was an exceptional, liberal man who strongly believed in the importance of female education. Rukhmabai continued her studies after her marriage.

- Dadaji Bhikaji was an improvident and uneducated youth with no prospects and no signs of interest in pursuing an education.

- Despite being married, Rukhmabai and Dadaji never lived together and she continued to stay with her mother and step-father even after marriage.

- Bhikaji lived a dissolute life by all accounts and later insisted Rukhmabai join him and begin their marital life.

- The decision was perhaps motivated by monetary intent as Rukhmabai had inherited a lot of wealth from her father.

- Rukhmabai refused to move in with him stating that she was married to him as a child and thus had no say in the marriage and they lacked compatibility.

- She continued to live with her stepfather and pursued her education, going against the norms of society.

- Her stepfather supported her in this decision.

- In 1884, Dadaji sent a legal notice to Sakharam through his lawyers, asking him to stop preventing Rukhmabai from living with him.

- Eventually, the matter went to court and was finally resolved in 1887.

- During this period, Rukhmabai evolved into an intelligent young woman. She would read books borrowed from the Free Church Mission Library.

- She would attend Prarthana Samaj and Arya Mahila Samaj meetings with her mother, interact with Europeans and other social reformers that her father knew and so on.

Struggle for rights and dignity

- In 1885, Bhikaji sought “restitution of conjugal rights (RCR)” where the hearing and judgement were presided over by Justice Robert Hill Pinhey.

- The prevailing legal provisions at the time of Rukhmabai’s case offered two types of matrimonial suits for obtaining conjugal rights recognized under the law. These were:

- Under the Indian Limitation Act 1877, a suit for RCR (Restitution of conjugal rights) could be brought by either party, but the suit for “the recovery of a wife” was only available to men and both these suits had to be brought within two years of the spouse’s refusal to cohabit.

- Section 260 of the revised Code of Civil Procedure 1882 prescribed prison (up to six months) or the attachment of property if either partner defied the law.

- Rukhmabai defended the suit and submitted three main reasons for her refusal to do so. These were: Bhikaji’s inability to provide for proper maintenance and residence for the couple, his ill health, and the character of the people with whom he lived.

- However, her refusal of her husband was an act of resistance, challenging the very convention of child marriage.

- Rukhmabai’s two letters to the editor in the daily The Times of India under the pseudonym “A Hindu Lady” are evidence of this assertion.

- In these letters, Rukhmabai proved herself as not only a resolute rebel but also an accomplished non-conformist and rationalist who challenged social conventions with arguments about gender abuses in Hindu society.

- She also made impassioned pleas against child marriage, widowhood, illiteracy, and domestic cruelty.

- She also stressed how early marriage restricted the young bride’s access to education and her mental and physical freedom.

- She urged the government to raise the minimum age of marriage to fifteen for girls and twenty for men.

- The British precedents could not be implied in this case, as British law was meant to be applied in the case of consenting adults.

- Justice Pinhey found this limitation in British law and found no previous cases of such nature in Hindu law and argued that to compel Rukhmabai to consummate her marriage against her wishes would be “a barbarous, a cruel, a revolting thing to do”.

- Hence his judgement on the case stated that Rukhmabai had been wed as an innocent child, had no say in the matter and now couldn’t be forced.

- The judgement stirred widespread protests and agitations across the country, especially by orthodox Hindus since a majority of Hindu marriages at that time were arranged and performed while the bride was still a child.

- Many Hindus argued that the law did not respect Hindu rituals and customs.

- However, some praised reformative the step.

- Soon after Pinhey gave the decree, Bhikaji filed an appeal. The case came up for retrial in the year 1886.

- In 1887, Rukhmabai was ordered to live with her husband or spend six months in jail. She was also asked to pay Bhikaji’s costs for the original hearing.

- In the meantime, Indian reformers and British feminists began approaching their governments on behalf of Rukhmabai, eventually petitioning Queen Victoria to dismiss the case against her.

- Rukhmabai decided not to return to Dadaji and to continue her education. She agreed to face the maximum penalty rather than accept the verdict given.

- The verdict was subsequently overruled by Queen Victoria. Bhikaji accepted monetary compensation of two thousand rupees and agreed to never execute the decree for restitution of conjugal rights awarded against her and dissolve the marriage. He soon remarried.

- Rukhmabai legally separated from her husband in 1888 and moved to England to study medicine.

Age of Consent Act, 1891

- Rukhmabai’s prolonged and persistent struggle for her rights and fight against the patriarchal law initiated processes of social and legal change in India.

- The case was widely discussed and debated producing strong responses from all sections of society.

- It was a feminist movement of its kind because it unified Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Parsi Indian women as well as British feminists. It got a lot of attention in Britain where women’s magazines covered it.

- The case also gave rise to debates and agitations against child marriage in the next decade and initiated the Age of Consent movement in India, which eventually led to the increase of the minimum age of marriage to twelve for girls through the Age of Consent Act, 1891.

Career

- After the case closed, Rukhmabai decided to study medicine and moved to England. In 1889, she joined the London School of Medicine for Women.

- She was supported by Dr Edith Pechey of Bombay’s Cama Hospital, activists, and fellow Indians in England to complete her course at the London School of Medicine for Women.

- After completing her degree in medicine, Rukhmabai returned to India in 1894 to serve as a medical practitioner.

- Rukhmabai was aware of the poor state of women’s healthcare in India and the lack of medical practitioners and health awareness. She realized the need for women doctors in India and medical facilities for women especially.

- She joined a hospital in Surat, declining an offer from Women’s Medical Service to join a state hospital in Rajkot run for women.

- Rukhmabai served as the chief medical officer for almost thirty-five years in Surat and Rajkot.

- She was supported by Eva McLaren, Walter McLaren and the Countess of Dufferin’s Fund for supplying medical aid to women in India.

- During the same period, she kept voicing her concerns against social evils like child marriage and the prevalent practice of ‘purdah’.

Death

- She passed away in 1955 when she was ninety-one years old while battling lung cancer.

Literary works and quotes

- Literary works

- ‘Indian Child Marriage (an Appeal to the British Government)’.

- ‘Purdah – the Need for its Abolition’.

- Quotes

- “I am not afraid; I will not give up in any circumstances.”

- “I am one of those unfortunate Hindu women whose hard lot it is to suffer the unnameable miseries entailed by the custom of early marriage. This wicked practice has destroyed the happiness of my life, it comes between me and the thing which I prize above all others-study and mental cultivation.”

- “Marriage does not interpose any insuperable obstacle in the course of their (men’s) studies. They can marry not only a second wife, on the death of the first, but have the right of marrying any number of wives at one and the same time, or any time they please.”

- “Within our reach lies every path we ever dream of taking. Within our power lies every step we ever dream of making. Within our range lies every joy we ever dream of seeing. Within ourselves lies everything we ever dream of being.”

Nice 🌸