Section 79 vs Section 69A: X Corp’s Legal Fight Against India’s Online Censorship Framework

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 85+ questions reflected

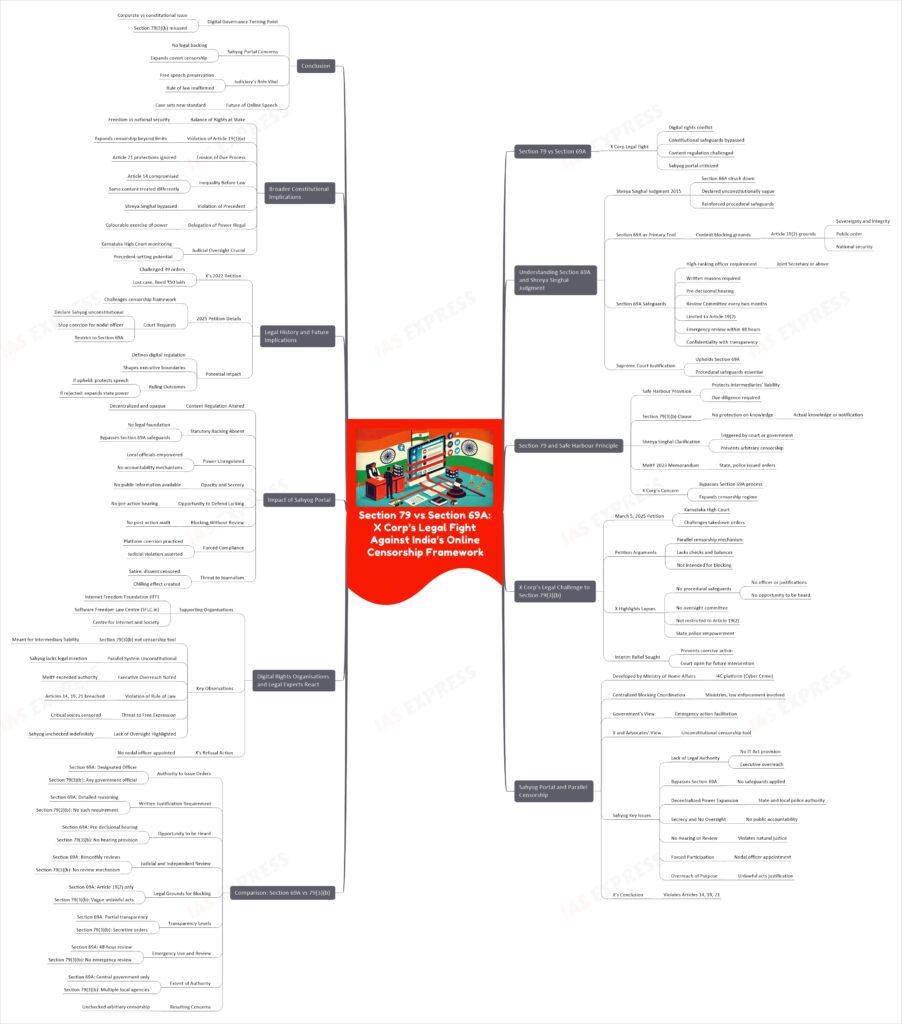

The ongoing legal battle between Elon Musk-owned X Corp (formerly Twitter) and the Indian government has sparked a broader conversation around digital rights, censorship, and constitutional safeguards in India. At the heart of this confrontation lies the government’s alleged misuse of Section 79(3)(b) of the Information Technology Act, 2000, to bypass established legal safeguards for content blocking. X Corp has filed a petition in the Karnataka High Court challenging the Centre’s expanding content regulation regime, particularly the use of Section 79(3)(b) and the Sahyog portal, which the company and digital rights organisations call a parallel censorship system. This article explains the intricacies of the case, the laws involved, and the potential implications for digital freedom and governance in India.

Understanding Section 69A and Shreya Singhal Judgment

- In 2015, the Supreme Court delivered a landmark judgment in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, where it struck down Section 66A of the IT Act for being “unconstitutionally vague”. This judgment reinforced the importance of procedural safeguards in content regulation.

- Post this ruling, Section 69A of the IT Act emerged as the primary legal provision for online content blocking. It authorizes the Central Government to block information under specific grounds provided in Article 19(2) of the Indian Constitution, such as sovereignty, public order, and national security.

- Section 69A includes several key safeguards:

- Only a high-ranking Designated Officer (Joint Secretary or above) can issue blocking orders.

- Detailed written reasons must be recorded.

- A pre-decisional hearing must be provided to content creators and intermediaries.

- An independent Review Committee must review the orders every two months.

- Blocking must be limited strictly to the grounds listed under Article 19(2).

- Emergency blocking orders must undergo review within 48 hours.

- Confidentiality must be maintained, while allowing judicial oversight and transparency.

- The Supreme Court upheld Section 69A in Shreya Singhal only because it found the provision to be narrowly tailored and accompanied by procedural safeguards essential to protect freedom of expression under Article 19(1)(a).

Section 79 and the Safe Harbour Principle

- Section 79 of the IT Act was designed to protect intermediaries—such as social media platforms—from legal liability for content posted by users. It provides a legal “safe harbour”, shielding platforms from being held accountable for third-party content as long as they adhere to certain due diligence requirements.

- However, Section 79(3)(b) states that this safe harbour does not apply if the intermediary, upon receiving actual knowledge or government notification, fails to remove unlawful content.

- The Supreme Court clarified in Shreya Singhal that “actual knowledge” under Section 79(3)(b) should only be triggered by a court order or a valid government notification under Article 19(2) grounds. This was to prevent arbitrary censorship and to ensure that intermediaries are not burdened with deciding what is illegal.

- Despite these clarifications, in 2023, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) issued an office memorandum authorizing various government bodies, including state governments and local police, to issue blocking orders under Section 79(3)(b).

- This directive, according to X, unlawfully expands the blocking regime beyond Section 69A, bypassing the procedural safeguards that were affirmed in the Shreya Singhal ruling.

X Corp’s Legal Challenge to Section 79(3)(b)

- On March 5, 2025, X Corp filed a writ petition in the Karnataka High Court challenging the government’s use of Section 79(3)(b) for issuing content takedown orders.

- The petition argues that this provision is being misused to create a parallel censorship mechanism without the checks and balances mandated by Section 69A.

- X contends that Section 79 was never intended to grant content blocking powers to the government. Instead, it only provides a framework for when intermediaries can lose their legal immunity.

- The company has highlighted that:

- Section 79(3)(b) lacks procedural safeguards such as a designated officer, written justifications, and the opportunity for content creators to be heard.

- There is no oversight committee or review process as mandated under Section 69A.

- Blocking under this section is not restricted to Article 19(2) grounds, allowing arbitrary and vague criteria for censorship.

- It empowers state governments and even local police to issue takedown orders, massively decentralizing and diluting the oversight mechanism.

- X has requested an interim order preventing coercive action against it for refusing to comply with takedown requests under Section 79(3)(b). While the court has not granted immediate relief, it has kept the door open for X to seek further intervention if action is taken against it.

The Sahyog Portal and the Parallel Censorship System

- X’s petition also spotlights the Sahyog portal, developed by the Ministry of Home Affairs through the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C).

- The Sahyog portal is designed as a centralized system where ministries, law enforcement, and social media platforms can coordinate on content blocking and data requests.

- According to the government, the portal helps facilitate faster action, especially in emergencies like missing children or cybercrime cases. However, X and digital rights advocates argue that it is an unconstitutional censorship tool.

- The key issues with the Sahyog portal include:

- Lack of Legal Authority: There is no provision in the IT Act allowing the creation of such a portal for content blocking. The portal is seen as an executive overreach.

- Bypassing Section 69A: The portal allows content blocking without following the safeguards established in Section 69A.

- Decentralized Power: It authorizes numerous agencies, including state and local police, to issue blocking orders, diluting accountability and enabling arbitrary censorship.

- Secrecy and No Oversight: There is no transparency about who issues the orders, why they are issued, and whether they are reviewed or not. Users and intermediaries are not informed, and there is no mechanism to appeal.

- No Hearing or Review: Unlike Section 69A, the portal does not mandate any pre-decisional hearing or post-decisional review, violating principles of natural justice.

- Forced Participation: Intermediaries like X are being forced to appoint nodal officers and comply with requests from Sahyog, despite the lack of statutory backing for such obligations.

- Overreach of Purpose: While Section 69A limits blocking to national interest concerns, Sahyog facilitates blocking for vaguely defined “unlawful acts,” extending censorship to areas like dissent, criticism, and even satire.

- In X’s view, the Sahyog portal represents an unconstitutional regime of secretive, large-scale censorship that directly violates Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Comparison Between Section 69A and Section 79(3)(b): Erosion of Safeguards

- Experts and legal commentators have pointed out significant differences between Section 69A and Section 79(3)(b), highlighting how the latter erodes established legal standards:

- Authority to Issue Orders:

- Section 69A: Only a Designated Officer (Joint Secretary level or above) can issue content blocking orders.

- Section 79(3)(b): No such limitation. Local police or junior officials from various ministries can issue takedown requests, drastically widening the power base.

- Requirement of Written Justification:

- Section 69A: Blocking orders must include detailed reasoning and can be scrutinized judicially.

- Section 79(3)(b): No such requirement. Orders can be vague or even verbal, making them hard to challenge in court.

- Opportunity to be Heard:

- Section 69A: Mandates pre-decisional hearing for content creators and platforms.

- Section 79(3)(b): No such provision. Content can be removed without any notice or defense.

- Judicial and Independent Review:

- Section 69A: All orders are reviewed every two months by a committee to prevent misuse.

- Section 79(3)(b): No review mechanism exists, allowing indefinite takedowns.

- Legal Grounds for Blocking:

- Section 69A: Must be based on constitutional grounds like sovereignty, public order, etc., under Article 19(2).

- Section 79(3)(b): Allows for vague interpretations of “unlawful acts,” not necessarily linked to Article 19(2).

- Transparency:

- Section 69A: Has certain transparency requirements, though often ignored.

- Section 79(3)(b): No formal transparency process; orders are secretive and inaccessible to the public or even the affected user.

- Emergency Use and Review:

- Section 69A: Emergency orders must be reviewed within 48 hours.

- Section 79(3)(b): No emergency procedure or review mandate.

- Extent of Authority:

- Section 69A: Centralized with the Union Government only.

- Section 79(3)(b): Empowers multiple agencies, including local police, leading to uncontrolled censorship.

- Authority to Issue Orders:

- These differences illustrate how the misuse of Section 79(3)(b) creates a looser, arbitrary framework with fewer checks, opening doors for censorship that goes unchecked and unchallenged.

Digital Rights Organisations and Legal Experts React

- Prominent digital rights groups such as the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC.in), and Centre for Internet and Society have supported X’s legal challenge.

- Key observations and critiques from experts include:

- Section 79(3)(b) is Not a Censorship Tool:

- Legal experts argue that Section 79(3)(b) is not an independent tool for blocking content. Instead, it was meant to define when intermediaries lose legal immunity—not to authorize the government to issue blocking orders.

- Parallel System is Unconstitutional:

- The Sahyog portal is not mentioned in any law or rules. Its operations violate the IT Act and go against the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shreya Singhal, which established the constitutional boundaries for online censorship.

- Executive Overreach:

- The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) has issued directives beyond its authority, effectively bypassing judicial and legislative scrutiny.

- Violation of Rule of Law:

- Without legal backing, the Sahyog portal and use of Section 79(3)(b) are ultra vires (beyond legal power), violating constitutional principles under Articles 14 (equality before the law), 19 (freedom of speech), and 21 (due process).

- Threat to Free Expression:

- The current regime allows arbitrary takedowns of critical voices, satire, or dissent under the broad label of “unlawful acts,” posing a significant threat to free speech.

- Lack of Oversight:

- With no external checks or committee review, orders through Sahyog can continue indefinitely without being questioned or evaluated.

- Section 79(3)(b) is Not a Censorship Tool:

- X has also refused to appoint a nodal officer for Sahyog, citing the lack of legal compulsion and has asked the Karnataka High Court to protect it from any punitive measures for this non-compliance.

Impact of Sahyog Portal on Content Regulation and Free Speech

- The creation and functioning of the Sahyog portal have significantly altered how content takedown and data access requests are managed in India, raising serious concerns about digital rights and state overreach.

- Absence of Statutory Backing:

- The Sahyog portal does not derive authority from any existing law or provision in the IT Act. Its implementation by the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) is purely executive in nature.

- Section 69A is the only recognized legal route for content blocking. Using Section 79(3)(b) to run Sahyog bypasses this, creating a parallel framework without legislative or judicial sanction.

- Unregulated Expansion of Power:

- Ministries, state governments, and even local police officers have been empowered to issue takedown orders using Sahyog. This vastly expands censorship powers without any corresponding accountability.

- A large number of blocking orders can now be issued across jurisdictions, with little to no oversight or consistency.

- Opacity and Secrecy:

- Orders issued via Sahyog are not made public. There is no clarity about the number of orders, the agencies involved, or the basis of takedown requests.

- This secrecy makes it difficult for platforms or affected individuals to challenge such orders legally.

- No Opportunity for Defense:

- Under Section 69A, content originators and intermediaries are meant to be given a hearing before content is blocked.

- In contrast, Sahyog does not allow users or platforms to respond before action is taken, violating the principle of natural justice.

- Permanent Blocking Without Review:

- Sahyog does not mandate any periodic review of blocking orders. Once content is taken down, it may remain inaccessible indefinitely.

- This absence of a review mechanism contradicts the constitutional safeguard of judicial oversight and the Supreme Court’s guidance in Shreya Singhal.

- Forced Compliance on Private Entities:

- The Ministry of Home Affairs has asked platforms like X to designate nodal officers to comply with Sahyog orders.

- X has argued this is coercive and amounts to forced participation in an unconstitutional censorship system. The platform already complies with due diligence under the IT Rules, 2021, and sees no lawful reason to register separately on Sahyog.

- Wider Threat to Journalism and Dissent:

- By allowing vague “unlawful acts” as a basis for takedown, Sahyog opens the door to targeting journalistic content, political dissent, and satire.

- Without clear boundaries, almost any content can be deemed illegal, risking mass over-censorship and self-censorship.

Legal History and Future Implications

- X’s legal battle is not its first challenge to India’s content regulation system. In 2022, the platform contested 39 blocking orders issued under Section 69A, arguing they were excessive and violated procedural safeguards.

- However, the Karnataka High Court dismissed that case and imposed a ₹50 lakh penalty on X, ruling that the government did have the authority to block entire accounts.

- In the current petition filed in 2025, the stakes are higher as X is contesting not just specific orders but the very framework through which the government is issuing them.

- X is asking the court to:

- Declare the Sahyog portal unconstitutional and ultra vires.

- Prevent coercive action for not appointing a nodal officer for the portal.

- Restrict blocking powers only to Section 69A, with full compliance to its procedural rules.

- X is asking the court to:

- The outcome of this petition could redefine how content regulation works in India, especially regarding the boundaries of executive power and protection of free speech.

- If the court upholds X’s arguments, it may reaffirm the necessity of judicial scrutiny and strict safeguards in online censorship. Conversely, if the court rules in favor of the government, it could set a precedent for broader, less accountable state control over digital content.

Broader Constitutional Implications and the Role of Judiciary

- X Corp’s challenge isn’t just about the legal technicalities of Sections 69A and 79(3)(b); it also raises fundamental questions about the balance between national security and freedom of speech in a democratic society.

- Violation of Article 19(1)(a):

- Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and expression. Any restriction on this right must be “reasonable” and conform to the specific exceptions listed under Article 19(2), such as public order, decency, or sovereignty.

- The use of Sahyog and Section 79(3)(b) introduces new, undefined justifications for censorship, expanding beyond Article 19(2) and violating constitutional protections.

- Erosion of Due Process under Article 21:

- Article 21 ensures that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except by the procedure established by law.

- Content takedown without hearing, notice, or legal basis violates procedural due process, undermining Article 21 protections.

- Inequality Before the Law (Article 14):

- The discretionary and arbitrary power given to various officials under Sahyog undermines the right to equality before the law.

- Without consistent standards or review mechanisms, similar content may be treated differently depending on who issues the takedown order.

- Violation of Supreme Court Precedent:

- In Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, the Supreme Court explicitly laid down conditions for content blocking, including safeguards like pre-decisional hearings, detailed justification, and limited grounds based on Article 19(2).

- The current practices under Sahyog and Section 79(3)(b) bypass these safeguards, directly contradicting the binding authority of the Supreme Court under Article 141 of the Constitution.

- Delegation of Non-Delegable Power:

- X has also argued that MeitY’s order encouraging ministries and state agencies to issue takedown notices unlawfully delegates powers that the central government itself does not possess.

- This is a “colourable exercise of power” — when a lawful provision is used to achieve an unlawful objective.

- Judicial Oversight is Crucial:

- The courts play a key role in ensuring that executive power does not override constitutional rights. The outcome of X’s petition will set a precedent for how India handles content moderation, censorship, and online freedom in the years to come.

- The Karnataka High Court has kept the matter pending and allowed X to approach the bench if any coercive action is taken against it, ensuring a legal recourse is available.

Conclusion

The legal battle between X Corp and the Indian government over the misuse of Section 79(3)(b) and the creation of the Sahyog portal marks a critical moment for digital governance in India. At the core of this conflict is the tension between the state’s need to regulate harmful or illegal content and the individual’s right to free expression and due process. The misuse of safe harbour provisions to enable a parallel censorship regime—bypassing the safeguards upheld in the Shreya Singhal case—represents a significant threat to constitutional principles.

Sahyog, despite being presented as a tool for efficiency, lacks legal backing, oversight, and transparency. Its use effectively turns India’s content moderation framework into a covert censorship mechanism, diluting accountability and expanding executive power in the digital space. The petition filed by X Corp is more than a corporate dispute—it is a call to reestablish the rule of law, ensure judicial scrutiny in censorship, and preserve democratic rights in the digital era.

How the judiciary responds to this challenge will shape the future of online speech, platform liability, and the architecture of digital regulation in India. The case is an opportunity to reaffirm that freedom of expression is not just a constitutional ideal but a lived reality, even in the digital age.

Practice Question

How does the use of Section 79(3)(b) of the IT Act by the government impact the constitutional safeguards provided under Article 19? (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.