2.0 Approaches to Employment Income and Interest Rate determination: Classical, Keynes (IS-LM) curve, Neo classical synthesis and New classical, Theories of Interest Rate determination and Interest Rate Structure

I. Introduction to Employment, Income, and Interest Rate Determination

Definition and Scope of Employment, Income, and Interest Rate Determination

- Employment:

- Refers to the total number of people employed in an economy, covering both formal and informal sectors.

- A crucial component of economic analysis since it influences overall production, demand, and growth.

- Employment levels are often measured by indicators like the unemployment rate, labor force participation rate, and the proportion of the workforce employed in different sectors, such as agriculture, industry, and services.

- In India, major employment surveys like the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) help assess employment trends.

- Employment directly impacts income distribution, particularly in economies with a large unorganized sector.

- Income:

- Income refers to the earnings derived from labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. It is categorized into wage income (salaries), profit (returns on entrepreneurship), and interest income (returns on capital investment).

- Per capita income, gross national income (GNI), and household income are significant indicators of economic prosperity and distribution in any country.

- In India, the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) tracks household income data, which influences policy formulation.

- The scope of income determination involves studying factors like skill level, education, technology, capital investment, and government policies such as taxation and social welfare programs.

- Interest Rate:

- Interest rates refer to the cost of borrowing or the return on savings. It is determined by various factors, including inflation, monetary policy, and the overall demand and supply of credit in the economy.

- Real interest rate refers to the nominal rate adjusted for inflation, while nominal interest rate is the rate before such adjustments.

- In India, interest rates are influenced by institutions like the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which sets the repo rate and reverse repo rate as part of its monetary policy.

- Different interest rates exist, such as the bank lending rate, government bond yields, and corporate debt rates, each serving specific financial functions.

Core Macroeconomic Questions Related to Employment and Income

- What determines the level of employment in an economy?

- Economists analyze the interaction between the labor market, output levels, and business cycles to understand what causes fluctuations in employment.

- Theories such as the Classical approach emphasize full employment as a natural state, while Keynesian economics highlights demand-side factors leading to underemployment.

- Tools like fiscal policy (government spending and taxation) and monetary policy (control of money supply and interest rates) are utilized to influence employment levels.

- How does income distribution affect economic growth?

- Uneven income distribution can lead to social unrest and hamper economic growth. Models like the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient quantify income inequality.

- In developing countries like India, income distribution is heavily influenced by factors like land ownership, education, and access to capital.

- The Indian government has adopted policies such as direct benefit transfers (DBT) and employment guarantee schemes like Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) to address income disparity.

- How do interest rates influence economic activities?

- Interest rates impact consumer behavior, investment decisions, and savings patterns.

- In India, changes in the repo rate directly affect home loans, car loans, and the cost of capital for businesses, leading to a ripple effect on sectors such as construction, automobiles, and real estate.

Historical Overview of Economic Thought Regarding Interest Rates

- Classical Perspective (18th-19th Century):

- Classical economists like Adam Smith (1723-1790) and David Ricardo (1772-1823) viewed interest rates as a natural outcome of the supply and demand for capital.

- They believed that interest rates balanced savings and investment, and therefore played a crucial role in the efficient allocation of resources in an economy.

- Jean-Baptiste Say’s (1767-1832) Say’s Law asserted that supply creates its own demand, implying that interest rates adjust naturally to maintain full employment.

- Keynesian Perspective (1930s):

- John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), in his seminal work The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), revolutionized the understanding of interest rates.

- Keynes introduced the concept of liquidity preference, where interest rates are determined by the demand for money as a store of wealth rather than the classical view of savings and investment equilibrium.

- He argued that in times of low demand, interest rates alone cannot restore full employment, necessitating active government intervention through fiscal policy.

- Neo-Classical and Monetarist Views (20th Century):

- The Neo-Classical synthesis combined elements of Classical and Keynesian thought, acknowledging short-term rigidities in interest rates while assuming that long-run equilibrium interest rates return to classical levels.

- Monetarists like Milton Friedman (1912-2006) emphasized the role of monetary supply and inflation expectations in interest rate determination. They argued that controlling the money supply is key to managing interest rates and inflation.

- Modern Perspectives:

- Contemporary economists examine factors like global liquidity flows, financial integration, and central bank policies when analyzing interest rate trends.

- In an interconnected world, global interest rate differentials, as seen in the varying policies of central banks like the Federal Reserve (USA), European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan, significantly influence domestic interest rates.

Significance of Employment, Income, and Interest Rate Determinants in Macroeconomic Models

- Employment and Economic Growth:

- Employment is central to macroeconomic models like the Solow Growth Model, where labor, alongside capital and technology, is a key input in determining output and growth.

- In models like the Phillips Curve, the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation highlights how employment levels influence broader economic conditions.

- In India, employment trends in key sectors such as agriculture (employing around 42% of the workforce as of 2022) play a crucial role in overall GDP growth and poverty alleviation.

- Income and Demand:

- Income levels directly affect aggregate demand in an economy. Consumption function models, such as Keynes’ consumption theory, show how income influences consumption patterns and, consequently, economic output.

- In India, schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) have significantly impacted income distribution and consumption patterns across different income strata.

- Interest Rates in Investment Decisions:

- Interest rates are pivotal in investment decisions, as highlighted in the Investment-Savings (IS) curve of the IS-LM model.

- In India, sectors like infrastructure, real estate, and manufacturing are heavily influenced by interest rate movements, with corporate bond yields and lending rates determining capital flows into these industries.

- The RBI uses tools like the repo rate (currently at 6.5% as of 2023) to manage inflation and stimulate or restrain investment based on economic conditions.

II. Classical Approach to Employment Determination

Overview of classical assumptions

- Rational behavior

- Classical economists assume that individuals act in their own self-interest to maximize utility (for consumers) and profits (for producers).

- Economic agents are fully informed, and there is perfect competition in the market.

- In the labor market, workers and firms make decisions that aim to maximize utility and profits, respectively, ensuring efficiency in employment decisions.

- Full employment

- Classical economics suggests that economies naturally tend toward full employment due to market-clearing mechanisms.

- Full employment implies that all available labor resources are being used efficiently in the production process.

- Unemployment, if it exists, is considered voluntary unemployment, meaning individuals choose not to work at the prevailing wage rates, or it’s due to temporary factors like frictional unemployment.

- Classical economists believe any excess supply of labor will lead to a reduction in wages, which in turn will restore full employment.

- Wage flexibility

- Classical theory holds that wages are perfectly flexible, meaning they can adjust up or down in response to changes in supply and demand for labor.

- Wage adjustments ensure that labor markets clear, preventing long-term unemployment.

- As wages fall, employers are encouraged to hire more workers, thus restoring equilibrium in the labor market.

Say’s Law: Mechanism and implications for employment

- Say’s Law

- Coined by Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), this law states that “supply creates its own demand.”

- In other words, the act of producing goods and services generates the income necessary to purchase those goods and services.

- In the context of employment, Say’s Law suggests that all workers who are willing to accept a wage will find employment since the production of goods will create enough demand for labor.

- Mechanism of Say’s Law

- Production and income: As firms produce goods, they generate income for workers and capital owners, which is then spent on goods, ensuring demand.

- No demand deficiency: Say’s Law rejects the possibility of a general glut or deficiency of demand in the economy because income earned from production will be used to purchase the produced goods.

- Implications for employment

- Say’s Law implies that unemployment is largely the result of wages being too high above the market-clearing level, leading to an excess supply of labor.

- As long as wages are flexible, the labor market will adjust, and full employment will be restored.

- The law also assumes that savings will automatically be invested, as interest rates will adjust to ensure that all saved funds are used for investment, maintaining demand.

Labor market equilibrium

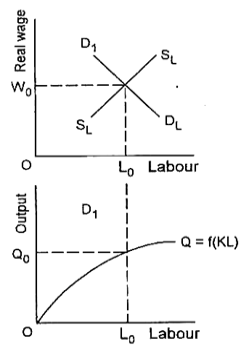

- Labor supply and demand functions

- In classical economics, the labor supply is determined by workers’ willingness to work at different wage levels, while labor demand is determined by employers’ willingness to hire workers at different wages.

- The labor supply curve slopes upward, indicating that as wages increase, more workers are willing to work.

- The labor demand curve slopes downward, indicating that as wages decrease, employers are willing to hire more workers.

- Equilibrium wage

- Labor market equilibrium occurs at the point where the labor supply equals labor demand.

- At this wage level, all workers willing to work at that wage are employed, and all employers looking to hire at that wage have filled their positions.

- Any deviation from this equilibrium is temporary, as wage flexibility ensures that the market will self-correct.

- Wage adjustments

- If there is a surplus of labor (unemployment), wages will fall, encouraging employers to hire more workers and restoring equilibrium.

- Conversely, if there is a shortage of labor (excess demand), wages will rise, encouraging more individuals to enter the labor market and reducing the shortage.

Real wages and employment

- Productivity and wage determination

- Classical economists argue that real wages (wages adjusted for inflation) are determined by the productivity of labor.

- An increase in labor productivity leads to higher real wages, as employers are willing to pay more for more productive workers.

- Relationship between real wages and employment

- In classical theory, if wages rise without a corresponding increase in productivity, unemployment will result because employers will hire fewer workers.

- Conversely, if productivity increases without a rise in wages, firms will hire more workers, reducing unemployment.

- Thus, there is a direct relationship between real wages and employment levels, with productivity acting as the key variable.

Critique of classical assumptions

- Wage and price rigidity

- Critics of classical economics point out that wages and prices are not as flexible in the real world as classical theory assumes.

- Wage stickiness: In many cases, wages are “sticky” downward, meaning they do not easily decrease even in the face of unemployment due to factors like labor contracts, minimum wage laws, and worker morale.

- Price rigidity: Prices of goods and services may also be inflexible, especially in the short run, due to costs associated with changing prices, known as menu costs.

- Voluntary vs involuntary unemployment

- The classical view assumes that any unemployment is voluntary, meaning individuals are choosing not to work at the going wage.

- However, critics argue that much of the unemployment seen in the real world is involuntary, meaning individuals are willing to work but cannot find jobs at the prevailing wage due to factors like demand deficiency and economic recessions.

- Real-world limitations of wage and price flexibility

- In many economies, particularly in developing countries like India, labor markets are highly segmented and not fully competitive.

- Issues such as informal labor markets, lack of mobility, and institutional constraints limit the flexibility of wages and prices.

- These factors contribute to persistent unemployment and underemployment, contradicting the classical assumption of self-adjusting markets.

III. Keynesian approach to employment determination

Keynes’ critique of classical theory

- Role of aggregate demand

- John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) challenged classical economics, emphasizing the role of aggregate demand in determining employment.

- In contrast to the classical belief in self-adjusting markets, Keynes argued that insufficient aggregate demand leads to involuntary unemployment.

- Aggregate demand is composed of consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports. When demand falls short, firms cut production, leading to unemployment.

- In a situation of demand deficiency, even if wages fall, it does not necessarily lead to higher employment because the underlying demand remains weak.

- Involuntary unemployment

- Unlike the classical notion of voluntary unemployment, Keynes introduced the concept of involuntary unemployment, where workers are willing to work at the current wage rate but cannot find jobs due to lack of demand.

- Keynes viewed this as a systemic problem rather than a temporary market imbalance, particularly during economic downturns or recessions, where demand for goods and services remains low.

- This marked a significant shift from the classical focus on supply-side factors like labor flexibility to demand-driven employment dynamics.

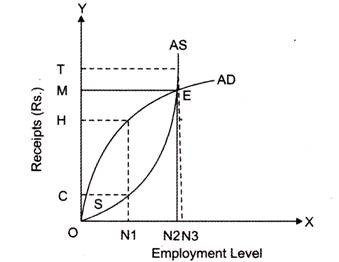

Concept of effective demand

- Effective demand definition

- Keynes introduced the concept of effective demand, which refers to the total demand for goods and services in the economy at a given time.

- Effective demand consists of aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) and aggregate supply (total production), and employment depends on the balance between these two forces.

- Employment levels rise only when effective demand is strong enough to justify firms expanding production and hiring more workers.

- Determinants of effective demand

- Several factors influence effective demand, including:

- Consumer confidence: Higher confidence leads to more consumption and investment.

- Government spending: Fiscal policy interventions increase aggregate demand, boosting employment.

- Investment decisions: Business expectations about future returns influence capital investment, which contributes to effective demand.

- Monetary policy: Interest rates, influenced by central banks like the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), impact borrowing costs and thus influence consumer spending and business investment.

- Foreign demand: Exports also contribute to effective demand.

- Several factors influence effective demand, including:

- Role in employment determination

- When effective demand is insufficient, firms reduce production and lay off workers, leading to cyclical unemployment.

- Keynes argued that government intervention through fiscal policy could raise effective demand and thus restore full employment.

- Effective demand explains why economies may remain stuck in low employment and low output levels without active policy measures.

Wage rigidity and unemployment

- Wage rigidity definition

- Keynes criticized the classical assumption of wage flexibility. He pointed out that in many real-world scenarios, wages are “sticky” downward, meaning they do not fall easily in response to unemployment.

- Reasons for wage rigidity include:

- Labor contracts: Many workers are protected by contracts that set fixed wages, preventing immediate wage cuts during economic downturns.

- Minimum wage laws: Governments set minimum wages to protect workers, limiting wage flexibility.

- Worker morale: Employers may avoid wage cuts to maintain worker morale and productivity, as wage reductions can lead to discontent.

- Persistent unemployment

- Wage rigidity leads to persistent unemployment because wages do not fall to market-clearing levels, as classical theory suggests.

- Even when aggregate demand is low, employers hesitate to reduce wages, leading to excess labor supply.

- In economies like India, informal labor markets exacerbate this problem, where many workers lack bargaining power, resulting in underemployment rather than wage adjustments.

- Keynes advocated for demand-side solutions rather than wage cuts, focusing on increasing effective demand to combat unemployment.

Government intervention

- Fiscal policies to boost aggregate demand

- Keynes was a strong proponent of government intervention in the economy to prevent deep recessions and unemployment.

- Fiscal policy includes government actions like increasing public expenditure or reducing taxes to stimulate economic activity and raise aggregate demand.

- During economic downturns, Keynes suggested that governments should increase spending on infrastructure, social programs, and other areas to create jobs and boost demand for goods and services.

- For example, India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) aims to provide guaranteed wage employment, increasing effective demand in rural areas.

- Counter-cyclical fiscal policies

- Keynes proposed counter-cyclical policies, where governments increase spending during economic downturns and reduce spending or increase taxes during boom periods to prevent inflation.

- This approach contrasts with classical laissez-faire economics, where minimal government intervention is preferred.

- Reducing unemployment

- Fiscal stimulus, like government-funded job creation programs, reduces cyclical unemployment by providing income to the unemployed, which in turn increases consumer spending and fuels further demand.

- Keynes also advocated for public works programs as a means of employing the unemployed while building public infrastructure.

- In India, public programs like Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) for affordable housing aim to stimulate both employment and demand in various sectors.

Criticisms and limitations of Keynes’ employment theory

- Short-term focus

- Critics argue that Keynesian theory focuses too heavily on short-term solutions, particularly government intervention through fiscal policies.

- Long-term solutions like structural reforms, improving productivity, and enhancing labor market flexibility are underemphasized in Keynesian models.

- In the long run, continual government intervention could lead to inefficiencies, higher debt levels, and inflationary pressures.

- Inflation risk

- A major criticism of Keynes’ employment theory is the risk of inflation resulting from excessive government spending.

- If fiscal stimulus is overused, it may cause demand to outstrip supply, leading to price rises.

- Historical examples, such as the 1970s stagflation (high inflation coupled with high unemployment), demonstrate the risks of inflationary pressures caused by Keynesian policies.

- In India, the challenge of food price inflation due to rising demand without adequate supply is a similar concern.

- Government debt

- Keynesian policies that rely on government borrowing to finance fiscal stimulus can lead to rising public debt.

- This can become unsustainable over time, particularly for developing economies like India, where the government may already face high deficits.

- Critics argue that continual deficit financing burdens future generations and may limit the government’s ability to respond to future economic crises.

- Crowding out effect

- Critics also point to the risk of the crowding out effect, where increased government borrowing raises interest rates, reducing private sector investment.

- Higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive for businesses, reducing investment in areas like infrastructure, manufacturing, and services, which are key to long-term growth.

- In countries with high government debt, like India, the crowding-out effect can hinder private sector growth, limiting job creation and innovation.

- Globalization and Keynesian policies

- In a globalized economy, the effectiveness of Keynesian policies can be limited by external factors such as global trade and capital flows.

- For example, fiscal stimulus in one country may lead to higher imports, benefiting foreign producers more than domestic industries.

- India, as a rapidly globalizing economy, faces challenges in implementing Keynesian policies due to its dependence on imports of goods like oil and technology.

- Additionally, global capital flows can undermine domestic fiscal policies by influencing interest rates and exchange rates.

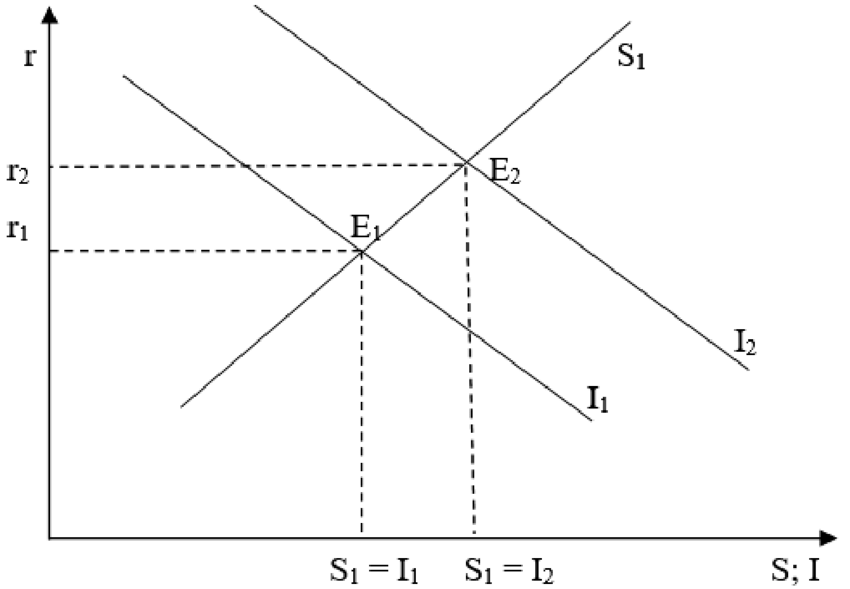

IV. Classical interest rate theory

Classical view on interest rates

- Interest as a reward for abstinence

- In classical economics, interest rates are viewed as the reward for abstinence or postponing consumption.

- Classical theorists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo argued that individuals save a portion of their income instead of consuming it immediately, and interest is the compensation they receive for delaying this consumption.

- This theory aligns with the notion that savings are necessary to fund investment and economic growth.

- Supply and demand of loanable funds

- The classical theory of interest is based on the loanable funds theory, which states that interest rates are determined by the interaction between the supply and demand for loanable funds.

- Supply of loanable funds comes from household savings, government surplus, and foreign savings. These funds are available for lending to businesses and individuals.

- Demand for loanable funds comes from businesses seeking to invest in capital goods, individuals borrowing for consumption, and governments borrowing to finance their deficits.

- The equilibrium interest rate is determined where the quantity of loanable funds supplied equals the quantity demanded.

- Savings and investment functions

- Savings function: Savings are influenced by the interest rate, as higher interest rates encourage individuals to save more, while lower rates lead to reduced savings.

- Investment function: Investment is inversely related to interest rates. Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing for businesses, thus discouraging investment in new projects or capital goods. Conversely, lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper and stimulate investment.

- The classical theory holds that interest rates ensure that savings and investment are always in equilibrium, promoting efficient resource allocation.

Determinants of interest rates in classical theory

- Time preference

- Time preference refers to the idea that individuals prefer present consumption over future consumption. In other words, people value goods and services more today than they would in the future.

- Interest rates act as compensation for deferring current consumption in favor of future consumption.

- The rate of time preference varies among individuals, and those with a lower preference for immediate consumption will be more willing to save, increasing the supply of loanable funds and lowering interest rates.

- Productivity of capital

- The classical view also links interest rates to the productivity of capital, meaning the return on investment that can be earned from utilizing capital in productive activities.

- Higher productivity of capital increases the demand for loanable funds, as businesses seek to invest more to maximize returns, which can drive up interest rates.

- The rate of interest is influenced by the expected return on capital, as firms will only borrow if they believe their investment will generate returns greater than the cost of borrowing.

Classical vs Keynesian views on interest rates

| Aspect | Classical View | Keynesian View |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Supply and demand for loanable funds | Liquidity preference and demand for money |

| Role of money | Passive; interest rates adjust savings | Active; interest rates determined by money |

| Policy implications | Focus on promoting savings and investment | Focus on managing aggregate demand and money |

| Interest rate determination | By savings-investment equilibrium | By money supply and liquidity preferences |

| Investment function | Inversely related to interest rates | Depends on interest rates and marginal efficiency of capital |

- Classical focus

- Classical economists focus on the relationship between savings and investment. They believe that the interest rate adjusts to ensure the equality of these two variables, thereby maintaining economic equilibrium.

- Money plays a passive role in classical economics. Interest rates adjust naturally, without requiring government intervention, as part of the self-regulating market mechanism.

- Savings are encouraged as a means to fund investment, which is considered critical for economic growth.

- Keynesian focus

- Keynesian theory, introduced by John Maynard Keynes, views interest rates through the lens of the liquidity preference theory. In this view, interest rates are determined by the demand for money, as individuals hold money for transactional, precautionary, and speculative motives.

- Unlike the classical theory, Keynesian economics gives a more active role to money and central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), in influencing interest rates.

- Keynesians advocate for the use of monetary policy to manage aggregate demand and stabilize the economy, particularly during periods of low demand and high unemployment.

- Differences in policy implications

- Classical policy implications focus on promoting savings and investment by ensuring that interest rates are determined by the market forces of supply and demand. Governments are advised to avoid interference, as market forces will naturally bring about equilibrium.

- In contrast, Keynesian policy implications emphasize the need for active government intervention through fiscal and monetary policies. Keynesians argue that during times of economic downturn, interest rates may not fall sufficiently to stimulate investment, necessitating government spending to boost demand.

- In India, Keynesian approaches have influenced monetary policies where the RBI actively adjusts interest rates through mechanisms such as the repo rate to stimulate or control economic activity.

V. Keynesian theory of interest rates

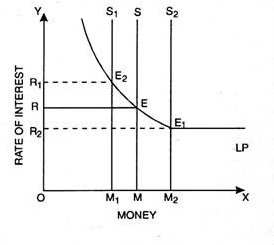

Liquidity preference theory

- Explanation of liquidity preference theory

- John Maynard Keynes introduced the liquidity preference theory in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936).

- The theory asserts that interest rates are determined by the demand for money (liquidity) and the supply of money in the economy.

- People prefer holding money instead of other assets due to its liquidity, and this preference influences the rate at which they are willing to part with it.

- The interest rate is the “price” that equilibrates the supply of money and the demand for money.

- Critique of liquidity preference theory

- Critics argue that liquidity preference overlooks the importance of savings and investment in determining interest rates, as emphasized in classical economics.

- Additionally, the theory assumes that the demand for money is relatively stable, but in reality, it can fluctuate with factors like inflation and speculative activities.

- Some economists believe that Keynes’ focus on liquidity preference may downplay the long-term productivity and time preference aspects influencing interest rates.

Motives for liquidity demand

- Transactionary motive

- Individuals and businesses demand money for transactions—buying goods and services or paying wages.

- The need for liquidity to facilitate day-to-day operations makes up the transactionary demand for money.

- This demand is influenced by the level of income and economic activity in the economy.

- Precautionary motive

- People and firms hold money as a precaution against unexpected future events, such as emergencies or unforeseen expenses.

- This motive becomes stronger during times of economic uncertainty or recession, when liquidity is more valued for security.

- In India, during periods of financial instability, households tend to increase their savings for precautionary reasons.

- Speculative motive

- The speculative motive relates to the demand for money as an asset to take advantage of future fluctuations in interest rates.

- When people expect interest rates to fall, they prefer holding money rather than bonds, as bond prices would rise with falling interest rates.

- Conversely, when people expect rates to rise, they reduce their money holdings in favor of bonds.

- The speculative motive is more prevalent among investors and financial institutions that actively seek returns through interest rate movements.

Money market equilibrium

- Interaction between money supply and interest rates

- The equilibrium interest rate in Keynesian theory is achieved when the supply of money, controlled by central banks, matches the demand for money based on the three liquidity motives.

- If money supply increases, interest rates will decrease, leading to higher investment and consumption.

- Conversely, a decrease in money supply raises interest rates, reducing borrowing and slowing down economic activity.

- India’s Reserve Bank of India (RBI) plays a key role in adjusting the repo rate to control money supply and influence interest rates.

- Shifts in money demand and supply

- Shifts in the demand for money can occur due to changes in income, inflation expectations, or investor sentiment.

- The supply of money is altered by central bank policies, like adjusting the repo rate, open market operations, and other tools in monetary policy.

- When the RBI reduces the repo rate, it increases money supply, leading to lower interest rates and stimulating investment and consumption.

- In contrast, raising the repo rate contracts money supply, leading to higher interest rates, which curbs inflation but may slow down investment.

Role of central banks

- Monetary policy as a tool for interest rate control

- Central banks, such as the RBI, use monetary policy to influence interest rates and stabilize the economy.

- Key tools include adjusting the repo rate, conducting open market operations, and modifying reserve requirements for commercial banks.

- The repo rate in India, for example, serves as a crucial instrument for controlling inflation and stimulating or cooling economic activity.

- By raising the repo rate, the RBI can curb inflation but risk slowing down growth, while lowering it encourages investment but may increase inflationary pressures.

- Central bank independence

- Central banks operate independently to ensure that interest rate decisions are made free from political influence, which can often prioritize short-term gains over long-term stability.

- In India, the RBI was established in 1935, and its autonomy allows it to focus on price stability, monetary control, and financial stability.

- Independent decision-making ensures that monetary policy is effective in managing inflation and economic growth, preventing over-reliance on fiscal policy.

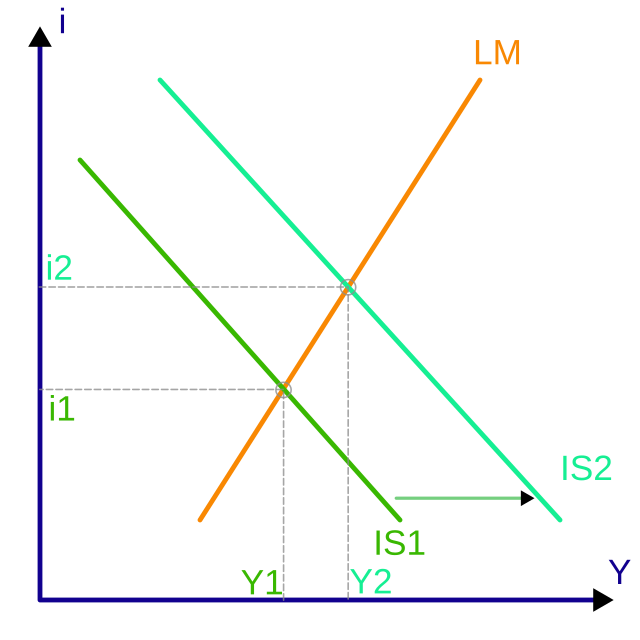

IS-LM framework

- Integration of goods and money markets

- The IS-LM model integrates the Investment-Savings (IS) curve and Liquidity preference-Money supply (LM) curve to show how goods and money markets interact to determine interest rates and output.

- The IS curve represents equilibrium in the goods market, where investment and savings balance at various levels of interest rates and income.

- The LM curve represents equilibrium in the money market, where the demand and supply for money balance at various interest rates and levels of income.

- Determining interest rates and output

- The point where the IS and LM curves intersect represents the equilibrium interest rate and output level in the economy.

- Changes in government spending or taxation shift the IS curve, while changes in the money supply shift the LM curve.

- In India, fiscal policy changes, such as increases in public expenditure through schemes like Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), impact the IS curve, while changes in monetary policy by the RBI affect the LM curve.

- During times of recession, a monetary expansion can shift the LM curve to lower interest rates and boost output, while fiscal expansion shifts the IS curve to increase demand and employment.

- Effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policies

- The IS-LM framework helps analyze the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policies under different economic conditions.

- When the economy faces a liquidity trap (a situation where interest rates are already very low, and further monetary expansion does not stimulate investment), fiscal policy becomes more effective in boosting demand.

- In normal economic conditions, monetary policy plays a significant role in adjusting interest rates to maintain equilibrium between demand and supply in both goods and money markets.

VI. IS-LM model

Structure of the IS curve

- Investment-savings equilibrium

- The IS curve represents the relationship between income and the interest rate in the goods market where investment (I) equals savings (S).

- At each point on the IS curve, the goods market is in equilibrium, meaning aggregate demand equals aggregate output.

- Investment is negatively related to the interest rate, as higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, thus reducing investment.

- Savings is positively related to income, as higher income levels lead to more savings by households.

- Determinants of the IS curve

- Investment demand is influenced by factors such as business expectations, cost of capital, and interest rates.

- Savings is influenced by household income levels, propensity to save, and interest rates.

- Fiscal policy plays a key role in shifting the IS curve. For instance, an increase in government spending raises aggregate demand, shifting the IS curve to the right. Conversely, tax hikes reduce disposable income, shifting the IS curve to the left.

- Indian context

- In India, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), a housing scheme, serves as an example of how public expenditure affects investment and savings, thereby influencing the IS curve.

Structure of the LM curve

- Money market equilibrium

- The LM curve represents the relationship between income and the interest rate in the money market, where the demand for money equals the supply of money.

- The demand for money depends on liquidity preferences, which are driven by the need for money for transactionary, precautionary, and speculative motives.

- The supply of money is controlled by the central bank, in India’s case, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The LM curve shows combinations of income and interest rates where the money market is in equilibrium.

- Liquidity preferences

- People hold money for different reasons:

- Transactionary demand: Money held for everyday transactions, which is influenced by income levels.

- Precautionary demand: Money held as a safeguard against uncertainties, such as sudden medical expenses or economic downturns.

- Speculative demand: Money held in anticipation of future interest rate changes. When interest rates are expected to fall, people prefer to hold money rather than bonds.

- As income increases, the demand for money also rises, pushing interest rates up unless the central bank increases the money supply.

- People hold money for different reasons:

- Central bank control over money supply

- In India, the RBI adjusts the repo rate to control the money supply and influence interest rates.

- A reduction in the repo rate increases the money supply, shifting the LM curve downward and reducing interest rates. Conversely, an increase in the repo rate contracts the money supply, shifting the LM curve upward and increasing interest rates.

Equilibrium in the IS-LM framework

- Simultaneous determination of income and interest rates

- The IS-LM model shows the interaction between the goods market and the money market, where the equilibrium levels of income and interest rates are determined.

- The point where the IS curve intersects with the LM curve represents the simultaneous equilibrium in both the goods and money markets.

- At this equilibrium, both the investment-savings balance in the goods market and the money supply-demand balance in the money market are achieved.

- Impact of changes in fiscal and monetary policies

- Fiscal policy changes (like increased government spending or taxation) shift the IS curve, while monetary policy changes (like adjusting the money supply) shift the LM curve.

- In India, fiscal expansion, such as increased spending on infrastructure projects like Bharatmala Pariyojana, can shift the IS curve to the right, raising income levels and pushing up interest rates.

- Monetary expansion by the RBI (such as lowering the repo rate) shifts the LM curve downward, leading to lower interest rates and higher investment and output.

Shifts in IS and LM curves

- Role of fiscal policies

- Expansionary fiscal policy: When the government increases spending or cuts taxes, aggregate demand rises, shifting the IS curve to the right. This raises both income and interest rates.

- Contractionary fiscal policy: When the government reduces spending or raises taxes, aggregate demand falls, shifting the IS curve to the left. This reduces income and interest rates.

- In India, measures like direct benefit transfers (DBT) during economic crises increase public consumption, shifting the IS curve rightward.

- Role of monetary policies

- Expansionary monetary policy: When the central bank increases the money supply (e.g., by lowering the repo rate), the LM curve shifts downward, reducing interest rates and increasing income.

- Contractionary monetary policy: When the central bank reduces the money supply (e.g., by raising the repo rate), the LM curve shifts upward, increasing interest rates and lowering income.

- In India, during periods of inflationary pressure, the RBI may raise the repo rate to tighten the money supply and control rising prices, shifting the LM curve upward.

Criticisms of the IS-LM model

- Assumptions of fixed prices

- One major criticism of the IS-LM model is its assumption of fixed prices in the short run, which may not hold true in real-world situations, especially in developing countries like India, where inflationary pressures often fluctuate.

- Price stickiness can distort the equilibrium predictions of the IS-LM framework. In times of rising inflation, income and interest rates may not adjust as the model predicts.

- Static framework

- The IS-LM model is a static framework that does not account for dynamic changes in the economy over time.

- It does not incorporate factors like technological progress, changing consumer preferences, or supply-side shocks that can affect the economy’s long-term trajectory.

- In the Indian context, supply shocks such as monsoon failures can drastically affect agricultural output, leading to shifts in income and consumption that the IS-LM model may not fully capture.

- Role of expectations

- Another criticism is that the IS-LM model does not sufficiently incorporate the role of expectations in determining economic outcomes.

- Investment decisions in the real world are often based on expectations of future profitability, which the IS-LM model treats as constant.

- For instance, if businesses expect future economic conditions to worsen, they may reduce investment, even if current interest rates are low.

- In India, changes in consumer and business sentiment, driven by policy announcements or global economic shifts, significantly influence economic decisions, something the IS-LM model cannot fully capture.

A shift in the IS curve from IS1 to IS2, indicating an increase in investment or government spending, leads to a new equilibrium at (i2, Y2) with higher income (Y2) and a higher interest rate (i2). The IS-LM model demonstrates how fiscal policy (shifting the IS curve) and monetary policy (shifting the LM curve) affect overall economic equilibrium in terms of both interest rates and national income.

VII. Neo-classical synthesis

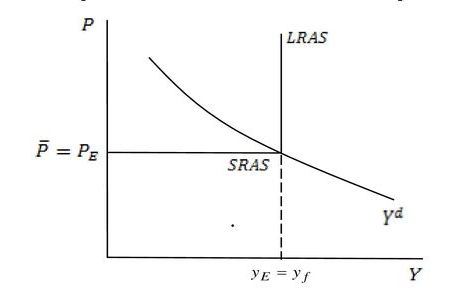

Overview of neo-classical synthesis

- Integration of classical and Keynesian elements

- The neo-classical synthesis blends the long-term equilibrium focus of classical economics with the short-term dynamic analysis of Keynesian economics.

- It accepts that in the long run, economies tend toward full employment and price flexibility, as described by classical theory.

- However, it incorporates Keynes’ insight that in the short run, economies can experience periods of unemployment, sticky prices, and fluctuations in aggregate demand, necessitating government intervention.

- Key economists

- Key contributors to the neo-classical synthesis include economists like Paul Samuelson, who formalized the synthesis in the 1940s and 1950s.

- Samuelson’s work integrated Keynesian short-run analysis with the classical long-run framework, forming the backbone of macroeconomic teaching and policy-making post-World War II.

Long-run classical equilibrium vs short-run Keynesian dynamics

- Long-run classical equilibrium

- The classical view holds that in the long run, markets are self-correcting, and economies reach full employment through the flexibility of wages and prices.

- Interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for loanable funds, and output converges to its potential level, driven by capital accumulation, technology, and population growth.

- No active government intervention is needed in the long run, as market forces bring about stability.

- Short-run Keynesian dynamics

- In the short run, economies can deviate from full employment due to demand-side shocks or price rigidities.

- Keynesian theory highlights the importance of aggregate demand and suggests that without intervention, unemployment can persist.

- Government policies like fiscal stimulus or monetary easing (e.g., cutting the repo rate by the Reserve Bank of India) can correct these short-run deviations and stabilize the economy.

- Transition and coexistence of frameworks

- The neo-classical synthesis allows for Keynesian interventions in the short run to manage fluctuations while assuming that the classical equilibrium reasserts itself in the long run.

- This framework implies that policymakers should use short-term interventions to address recessions, with the expectation that the economy will stabilize naturally over time.

Role of expectations in employment and interest rate determination

- Adaptive expectations

- Adaptive expectations theory suggests that individuals form expectations of future economic variables (like inflation or interest rates) based on past experiences.

- Over time, as individuals update their expectations in response to observed outcomes, employment and interest rates adjust, moving the economy toward equilibrium.

- In India, for example, if inflation consistently overshoots the RBI’s target, households may adjust their expectations, demanding higher wages, which in turn influences employment levels and interest rates.

- Rational expectations

- Rational expectations theory, advanced by economists like Robert Lucas in the 1970s, argues that individuals use all available information to form expectations about the future.

- This theory implies that if individuals expect government intervention, such as fiscal or monetary policies, they may adjust their behavior, potentially nullifying the intended effects of these policies.

- For instance, if Indian businesses expect future inflation, they might preemptively raise prices, making RBI’s efforts to control inflation through interest rate adjustments less effective.

Policy implications of the synthesis

- Monetary neutrality in the long run

- The neo-classical synthesis upholds the classical notion that monetary policy (e.g., changes in money supply) is neutral in the long run, meaning it affects prices but not real variables like output or employment.

- In the long term, changes in the money supply by institutions like RBI will only influence the price level, not real output or employment, as wages and prices fully adjust.

- Role of short-run interventions

- In the short run, monetary and fiscal policies can play a crucial role in stabilizing the economy by influencing aggregate demand.

- For example, during economic slowdowns, the Indian government might increase public expenditure or the RBI might reduce interest rates to boost demand and employment.

- These policies are essential to counter recessionary trends, as they mitigate short-term deviations from full employment.

- Keynesian and classical balance

- Policymakers are advised to balance short-term Keynesian interventions with long-term classical principles.

- In the Indian context, this might involve using short-term fiscal measures to address unemployment while ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability by controlling public debt.

Critiques of the neo-classical synthesis

- Over-reliance on equilibrium

- Critics argue that the neo-classical synthesis overemphasizes the concept of equilibrium, assuming that markets naturally return to balance after short-term disruptions.

- Real-world economies, especially in developing countries like India, face structural issues (e.g., labor market segmentation, institutional constraints) that prevent such easy adjustments, making equilibrium harder to achieve.

- The reliance on equilibrium may lead to underestimating the persistence of unemployment or inflation in the real world.

- Assumptions of price flexibility

- Another criticism is the assumption of price flexibility in the long run.

- In reality, prices and wages can remain sticky for extended periods due to factors like labor contracts, minimum wage laws, and informal labor markets in countries like India.

- These rigidities challenge the classical idea that wages and prices adjust automatically to restore full employment.

- Neglect of dynamic factors

- The synthesis also neglects dynamic factors such as technological change, globalization, and capital flows that can alter economic outcomes.

- In India, for instance, technological disruptions and global supply chain shocks (like those seen during the COVID-19 pandemic) had lasting effects on employment and productivity, which static models of equilibrium do not account for.

- Limited policy guidance for emerging economies

- The neo-classical synthesis offers limited guidance for economies like India that face structural constraints, such as informal labor markets or inequality.

- The assumption that market forces will restore equilibrium may not apply in economies where institutional weaknesses or social disparities are significant, necessitating more robust interventions.

VIII. New classical approach

Foundations of new classical economics

- Rational expectations

- Rational expectations theory is a cornerstone of new classical economics, introduced by Robert Lucas in the 1970s.

- It assumes that individuals use all available information, including current and future policy, to make decisions.

- Individuals and firms are forward-looking and adjust their behavior based on anticipated changes in economic conditions.

- This approach challenges Keynesianism by suggesting that economic policies may have little or no effect if people adjust their expectations accordingly.

- Market clearing

- The new classical approach assumes that markets, including labor and goods markets, are always in equilibrium or “market-clearing.”

- Price flexibility ensures that supply equals demand, and wages and prices adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.

- As a result, unemployment is viewed as voluntary, driven by workers’ decisions to reject available wages or jobs.

- In India, despite the theory of market clearing, wage rigidities in sectors like agriculture and informal labor markets challenge this assumption.

Role of information and expectations in employment and interest rates

- Perfect foresight

- In the new classical framework, agents are assumed to have perfect foresight, meaning they can predict future economic conditions accurately.

- This leads to efficient markets, where all available information is already factored into prices, wages, and interest rates.

- Employment decisions are made based on the anticipated future state of the economy, not just current conditions.

- For instance, Indian businesses may adjust hiring practices based on expectations of future economic growth or contraction.

- Impact on policy effectiveness

- Rational expectations reduce the effectiveness of traditional monetary and fiscal policies because individuals adjust their behavior in response to anticipated government actions.

- If the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announces an interest rate cut to boost investment, businesses may expect inflation to rise and therefore adjust their investment plans accordingly.

- This policy neutrality means that anticipated interventions do not have the intended effect, limiting the scope of short-term economic policies.

Natural rate of unemployment hypothesis

- Natural rate of unemployment

- Proposed by Milton Friedman and developed within the new classical framework, the natural rate of unemployment is the level of unemployment that persists in an economy due to structural factors and frictional unemployment.

- Unlike Keynesian economics, which emphasizes reducing unemployment through demand management, new classical economists believe that attempts to lower unemployment below the natural rate result in inflation without long-term gains in employment.

- In India, sectors like agriculture and informal labor markets experience frictional unemployment due to factors such as seasonal employment and job mismatch, which contribute to the natural rate.

- Long-term employment determination

- The natural rate hypothesis suggests that in the long run, employment levels are determined by structural factors like technology, market efficiency, and worker skills.

- Short-term fluctuations in employment caused by business cycles are temporary, as markets return to full employment over time.

- Government interventions aiming to reduce unemployment below the natural rate are seen as inflationary and unsustainable.

Interest rate determination

- Real business cycle models

- Real business cycle (RBC) models are a key feature of new classical economics, which argue that fluctuations in productivity—not demand—drive economic cycles.

- Interest rates are determined by productivity shocks and capital returns rather than changes in aggregate demand.

- These models assume that technology and external shocks cause changes in productivity, influencing both output and interest rates.

- In the Indian context, shifts in sectors like information technology and agriculture productivity can drive interest rate changes by affecting overall economic output.

- Focus on productivity shocks

- RBC models argue that productivity shocks explain most of the variation in interest rates and economic activity.

- Positive productivity shocks lead to increased investment demand, raising interest rates, while negative shocks reduce investment and lower rates.

- In India, productivity shocks from monsoon failures in agriculture or global supply chain disruptions in manufacturing can directly affect interest rates and business cycles.

Criticisms of new classical approach

- Overemphasis on rationality

- Critics argue that new classical economics places too much emphasis on rational expectations and assumes that individuals always act in perfectly rational ways.

- In reality, behavioral factors, imperfect information, and irrational decision-making often influence economic choices, making the assumptions of perfect rationality unrealistic.

- In India, where access to information and education varies widely, expecting rational behavior across the economy is challenging.

- Neglect of market frictions

- New classical models assume that markets clear and do not adequately account for market frictions, such as wage stickiness or transaction costs, that prevent smooth adjustments.

- In economies like India, where informal labor markets, regulatory bottlenecks, and institutional weaknesses are prevalent, these frictions play a significant role in shaping economic outcomes.

- Ignoring these factors leads to an overly simplistic view of how labor and goods markets function in practice.

- Policy limitations

- The new classical emphasis on policy neutrality suggests that government intervention is largely ineffective in stabilizing the economy.

- However, critics point out that during severe economic crises or structural recessions, active policies such as fiscal stimulus or monetary easing are necessary to restore stability.

- In India, the government’s intervention through measures like Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and direct benefit transfers (DBT) have been essential in addressing unemployment and boosting demand during economic downturns.

IX. Theories of interest rate determination

Overview of theories

- Loanable funds theory

- The loanable funds theory posits that interest rates are determined by the interaction between savings (supply of loanable funds) and investment demand (demand for loanable funds).

- This theory emphasizes the role of real factors such as income, time preference for consumption, and capital productivity in shaping interest rates.

- Higher savings lead to a greater supply of loanable funds, which reduces interest rates, while higher investment demand increases rates.

- Liquidity preference theory

- Introduced by John Maynard Keynes in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), this theory argues that interest rates are determined by the demand for money and the supply of money in the economy.

- Keynes identified three motives for holding money: transactionary, precautionary, and speculative motives.

- People demand money for liquidity purposes, and interest rates adjust based on the balance between this demand and the available money supply.

- Fisher’s equation

- Irving Fisher developed an equation to distinguish between nominal interest rates and real interest rates, where the nominal rate is adjusted for expected inflation.

- The Fisher equation is expressed as:

Nominal interest rate = Real interest rate + Expected inflation. - This theory highlights the role of inflation expectations in determining the nominal interest rate.

- It suggests that when inflation expectations rise, nominal interest rates will increase, even if the real interest rate remains constant.

Loanable funds theory

- Role of savings and investment

- The loanable funds theory focuses on the supply-demand balance between savings and investment.

- Savings come from households, businesses, and government budget surpluses, forming the pool of loanable funds.

- Investment demand comes from businesses looking to finance capital projects and individuals borrowing for consumption or housing.

- Interest rates serve as the price that clears the market, ensuring that all available loanable funds are allocated efficiently between savers and borrowers.

- An increase in savings lowers the interest rate, while a surge in investment demand pushes the interest rate upward.

- In India, factors like household savings rates, influenced by cultural preferences for savings and financial policies, play a significant role in determining interest rates.

Loanable funds vs liquidity preference

| Aspect | Loanable Funds Theory | Liquidity Preference Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Supply of savings and demand for investment | Demand for money and supply of money |

| Determinants | Real factors: income, time preference, productivity | Monetary factors: liquidity preferences, money supply |

| Interest rate adjustment | Clears the market for loanable funds | Balances money demand with money supply |

| Motives for holding assets | Based on return on capital or deferred consumption | Based on transactionary, precautionary, and speculative motives |

| Policy implications | Emphasizes policies that boost savings and capital formation | Focuses on central bank’s role in managing money supply |

Fisher’s theory of interest rates

- Real vs nominal interest rates

- Fisher’s theory distinguishes between real interest rates (reflecting the true return on savings or cost of borrowing after adjusting for inflation) and nominal interest rates (the stated interest rate before adjusting for inflation).

- For example, if the nominal interest rate is 7% and expected inflation is 3%, the real interest rate would be 4%.

- The real interest rate is crucial for long-term investments and savings decisions, while the nominal rate is more relevant for short-term loans and market conditions.

- Role of inflation expectations

- Fisher’s theory highlights that changes in inflation expectations have a direct impact on nominal interest rates.

- If expected inflation rises, lenders demand higher nominal interest rates to compensate for the reduced purchasing power of future interest payments.

- Similarly, if inflation expectations fall, nominal interest rates decline even if the real rate remains unchanged.

- In India, during periods of rising inflation, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) raises interest rates to curb inflation and stabilize the economy, reflecting Fisher’s insights.

Critiques of different interest rate theories

- Assumptions of market efficiency

- One critique of both the loanable funds and liquidity preference theories is their reliance on the assumption that markets are efficient and interest rates adjust quickly to balance savings and investment or money demand and supply.

- In reality, market frictions such as credit constraints, regulatory bottlenecks, and imperfect information can prevent such smooth adjustments, particularly in developing economies like India.

- Furthermore, institutional factors like the role of public sector banks in India and government interventions in the financial sector can distort the natural interest rate-setting mechanisms.

- Policy implications

- The loanable funds theory suggests that policies aimed at increasing savings or promoting investment will lead to higher growth by lowering interest rates and expanding the pool of loanable funds.

- However, critics argue that focusing solely on savings may ignore the importance of aggregate demand in stimulating economic activity, a key tenet of Keynesian economics.

- The liquidity preference theory places greater emphasis on the role of central banks, like the RBI, in managing monetary policy to control inflation and stabilize interest rates.

- Critics of this theory argue that in certain conditions, such as a liquidity trap, monetary policy loses its effectiveness, and fiscal policy may be more important for boosting demand.

X. Interest rate structure and term structure theories

Overview of interest rate structures

- Short-term vs long-term interest rates

- Short-term interest rates are rates applicable to loans or bonds with maturities of less than one year, often influenced by central bank policy and monetary actions like the RBI’s repo rate adjustments.

- Long-term interest rates apply to loans or bonds with maturities longer than one year, typically influenced by market expectations about future economic conditions, inflation, and the overall demand for capital.

- Short-term rates are usually lower due to the reduced risk over a shorter period, while long-term rates often carry a premium for additional risk and uncertainty over time.

- Yield curve

- The yield curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between interest rates (or yields) on bonds with differing maturities.

- A normal yield curve slopes upward, indicating higher interest rates for long-term bonds, reflecting greater risks and inflation expectations over time.

- An inverted yield curve occurs when short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates, often signaling an impending economic slowdown or recession.

- A flat yield curve suggests that short- and long-term interest rates are roughly equal, which can indicate uncertainty or a transition in the economic cycle.

Expectations theory of the term structure

- Future expectations of interest rates and inflation

- The expectations theory of the term structure suggests that the shape of the yield curve reflects investors’ expectations about future interest rates and inflation.

- If investors expect higher interest rates in the future, the yield curve will slope upward, as long-term bonds will require a higher return to compensate for the anticipated rise.

- Conversely, if investors expect lower future interest rates, the yield curve may flatten or invert, as long-term bonds would offer lower returns.

- In India, when inflation expectations rise, long-term government bond yields often increase, reflecting market expectations of tighter monetary policy by the RBI.

- Inflation impact

- Expected inflation directly influences the interest rate structure.

- Investors demand higher yields on long-term bonds if they expect inflation to erode the purchasing power of future interest payments.

- The RBI’s inflation targeting measures play a crucial role in shaping these expectations in India, particularly through its monetary policy announcements.

Liquidity preference theory of term structure

- Preference for shorter-term bonds

- The liquidity preference theory, initially proposed by John Maynard Keynes, argues that investors prefer shorter-term bonds due to the lower risk and greater liquidity associated with them.

- Longer-term bonds carry more uncertainty and are less liquid, so investors demand a higher yield, known as the term premium, to compensate for these risks.

- Role of risk

- The theory also emphasizes that the term premium grows with bond maturity due to the increased risk of fluctuations in interest rates, inflation, and economic conditions over time.

- In India, long-term infrastructure projects, such as those under Bharatmala Pariyojana, often rely on long-term bonds, which must offer higher interest rates to attract investors, given the greater risk and time horizon.

Market segmentation theory

- Supply and demand in different maturity segments

- The market segmentation theory posits that the interest rates for bonds of different maturities are determined by the supply and demand within each maturity segment.

- Markets for short-, medium-, and long-term bonds operate independently, and the yield in each segment is influenced by investor preferences, government policies, and the supply of bonds within that segment.

- This theory explains why the yield curve may not always follow the expectations or liquidity preference models.

- Investor preferences

- In the Indian context, pension funds or insurance companies may prefer long-term bonds due to their long-term liabilities, while corporate treasuries may prefer short-term bonds for liquidity management.

- Supply of bonds is affected by government borrowing needs, where shorter-term bonds are often used to meet immediate fiscal needs, while long-term bonds finance infrastructure or public projects.

Policy implications of term structure

- Central bank actions

- Central banks like the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) influence the short-term end of the yield curve through policy tools such as the repo rate and reverse repo rate.

- Changes in these rates affect the cost of borrowing for banks and, by extension, the broader economy, particularly influencing short-term interest rates.

- Yield curve targeting

- Some central banks, such as the Bank of Japan, have used yield curve control (YCC) to target specific rates along the yield curve, especially in the short-to-medium-term range, by buying or selling government bonds.

- Although the RBI has not formally adopted yield curve control, it indirectly affects the yield curve through its open market operations (OMOs) and management of government securities.

- Yield curve targeting can signal the central bank’s commitment to low borrowing costs, supporting growth, especially in times of economic distress.

XI. Comparative analysis of employment and interest rate theories

Classical vs Keynesian views on employment

| Aspect | Classical View | Keynesian View |

|---|---|---|

| Full employment | Assumes full employment in the long run | Unemployment can persist due to demand |

| Role of wages | Flexible, adjusts to balance markets | Sticky wages lead to unemployment |

| Unemployment causes | Voluntary, due to worker choices | Involuntary, driven by lack of demand |

| Market adjustments | Self-regulating through wage changes | Needs government intervention |

| Policy focus | Minimal government role | Active fiscal or monetary policies |

- Classical view on employment

- The classical approach assumes that the economy naturally tends towards full employment through flexible wages and market adjustments.

- Unemployment is typically seen as voluntary; workers choose not to accept available jobs due to the prevailing wage rates.

- Wages are fully flexible and adjust downward when there is an excess supply of labor, ensuring that markets clear without long-term unemployment.

- Keynesian view on employment

- Keynes argued that involuntary unemployment is possible, particularly during economic downturns, due to sticky wages and insufficient aggregate demand.

- Markets do not always clear naturally, and demand-driven unemployment can persist unless the government intervenes through fiscal policy (increased spending or tax cuts) or monetary policy (lowering interest rates).

Classical vs Keynesian vs Neo-classical views on interest rates

| Aspect | Classical View | Keynesian View | Neo-classical View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest rate basis | Market clearing between savings | Demand for money and liquidity | Rational expectations and productivity |

| Key determinant | Savings and investment | Liquidity preference | Productivity shocks and expectations |

| Role of money | Passive, no direct influence | Active, adjusts interest rates | Not central, productivity-driven |

| Government intervention | Minimal, free markets adjust | Needed to manage demand | Policy ineffective due to expectations |

- Classical view on interest rates

- Interest rates are determined by the supply of savings and the demand for investment.

- The market naturally clears as interest rates adjust to balance the supply and demand for loanable funds.

- Government intervention is generally unnecessary, as markets are viewed as self-correcting.

- Keynesian view on interest rates

- Liquidity preference drives the Keynesian view, where interest rates are determined by the demand for money for transactionary, precautionary, and speculative purposes.

- Interest rates adjust based on the availability of money in the economy, with a significant role for the central bank (like the RBI) in managing money supply through monetary policy.

- Neo-classical view on interest rates

- Neo-classical economists emphasize rational expectations and real factors like productivity shocks.

- Interest rates are driven by productivity and future expectations rather than the current demand for money.

- Government policies may have minimal impact due to the forward-looking behavior of agents who anticipate policy actions.

Role of government policy in different frameworks

- Classical framework

- The classical framework advocates for minimal government intervention, as markets are believed to adjust naturally.

- Fiscal policies are not considered necessary, as supply and demand for labor and capital balance themselves through flexible wages and prices.

- Keynesian framework

- Keynesians argue for active government intervention during economic slumps, through either fiscal policy (increased government spending, tax reductions) or monetary policy (lower interest rates, increasing money supply).

- Government actions are essential to boost demand and reduce unemployment during recessions, as markets may not naturally return to equilibrium.

- Neo-classical framework

- Neo-classical economists are skeptical of government intervention, suggesting that policy neutrality prevails due to rational expectations.

- Agents in the economy anticipate policy changes, making fiscal and monetary policies less effective in stabilizing the economy.

Short-run vs long-run dynamics

- Keynesian short-run focus

- Keynesians emphasize the importance of short-run dynamics, where economic output, employment, and interest rates can be influenced by aggregate demand and government intervention.

- Recessions and unemployment can persist in the short run if demand falls, necessitating active fiscal or monetary policies to boost spending and employment.

- Classical long-run equilibrium

- The classical approach stresses long-run equilibrium, where full employment is achieved naturally through market adjustments in wages and prices.

- Over time, any short-term disruptions, such as unemployment or inflation, will be corrected by the market without needing intervention.

- Neo-classical transition

- Neo-classical economists accept short-run fluctuations but argue that these deviations are driven by productivity shocks rather than demand-side issues.

- In the long run, the economy returns to natural rates of unemployment and stable interest rates based on productivity, with minimal need for policy interventions.

XII. Critique of classical and Keynesian theories

Strengths and weaknesses of classical theory

- Real-world applicability

- The classical theory’s core strength lies in its long-run equilibrium focus and belief in self-correcting markets.

- This approach assumes that market forces naturally adjust to shocks, leading to full employment through flexible wages and prices.

- Classical theory has been influential in shaping free-market policies that minimize government intervention, with emphasis on efficient resource allocation.

- However, classical economics struggles with real-world applicability, especially during periods of economic crises like the Great Depression (1929), where market forces failed to restore equilibrium without intervention.

- Flexibility assumptions

- Classical theory assumes that wages and prices are fully flexible and can adjust immediately to any shifts in supply and demand.

- In reality, wages are often sticky downward, meaning they do not easily fall during economic downturns due to labor contracts, minimum wage laws, and worker resistance.

- This leads to persistent unemployment, contradicting the classical belief that labor markets clear naturally.

- For example, in India, informal labor markets exhibit wage stickiness, where wages do not adjust as rapidly as classical theory suggests, leading to structural unemployment in certain sectors.

- Limited government role

- Classical theory argues for a minimal role of government, emphasizing laissez-faire policies where the economy self-regulates.

- While this works in stable conditions, it does not account for the need for fiscal or monetary intervention during deep recessions or periods of prolonged unemployment.

- Historical events like the 2008 global financial crisis demonstrated the need for government stimulus to jumpstart economies, challenging the classical model.

Critique of Keynesian theory

- Oversimplification of labor market dynamics

- Keynesian theory, with its focus on aggregate demand, is often criticized for oversimplifying labor market dynamics.

- By emphasizing government intervention to boost demand, it underestimates the complexity of the labor market, such as skill mismatches, regional unemployment disparities, and labor mobility issues.

- For instance, in India, policies like MGNREGA aim to increase rural employment, but these policies often fail to address the underlying structural problems in the labor market, such as skill shortages or infrastructure gaps.

- Underestimation of inflation risks

- Keynesian policies often focus on short-term solutions to unemployment and demand deficiencies, but they may ignore the potential for long-term inflationary pressures.

- Stimulating the economy through increased government spending or low-interest rates can lead to demand-pull inflation, where excess demand pushes prices higher.

- In developing economies like India, sustained government intervention can lead to rising inflation if not carefully managed, especially in sectors like food and energy.

- Keynesian policies may lead to fiscal deficits, where high public debt and inflation reduce the government’s ability to intervene in future crises.

- Dependency on government intervention

- Keynesian theory assumes that government intervention is always effective in managing economic cycles, but this overlooks the limits of fiscal and monetary policies in the long run.

- Government programs may become politically entrenched, leading to inefficient allocation of resources and a lack of long-term structural reforms.

Criticisms of interest rate theories

- Lack of consideration for market imperfections

- Classical and Keynesian interest rate theories both assume perfectly competitive markets where interest rates balance savings and investment, or money demand and supply.

- However, real-world financial markets often suffer from imperfections such as information asymmetry, credit constraints, and regulatory distortions.

- In countries like India, where public sector banks dominate the financial landscape, the interest rate mechanism does not function as smoothly as these theories suggest.

- Factors like government borrowing, subsidized credit programs, and regulatory hurdles influence interest rates beyond what classical or Keynesian models predict.

- Speculative behavior

- Interest rate theories tend to ignore speculative behavior in financial markets, where investors may act based on herd mentality or short-term gains rather than rational expectations.

- Asset bubbles, such as the 2008 housing crisis in the United States, often form when speculative activities drive prices and interest rates beyond sustainable levels.

- In India, speculative behavior in markets like real estate and stock markets can distort interest rates and lead to misallocation of capital, creating boom-bust cycles that are not fully explained by classical or Keynesian models.

- Interest rate rigidity

- Theories like loanable funds theory assume that interest rates are flexible and adjust according to market conditions.