4.3.3 Exchange Rate Adjustments under Capital Mobility | Balance of Payments (BOP) Adjustments

Module Progress

0% Complete

I – Introduction to Balance of Payments and Exchange Rate Adjustments

Definition and Scope of the Balance of Payments (BOP)

- Concept of Balance of Payments (BOP)

- A systematic record of all economic transactions between residents of a country and the rest of the world within a specific period, typically a year.

- Includes trade in goods, services, capital transfers, and financial flows.

- Maintained in accordance with guidelines set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, founded 1944) under the Balance of Payments Manual (BPM6, latest version 2009).

- Fundamental Structure of BOP

- Current Account

- Records all transactions of goods, services, income, and unilateral transfers.

- Components:

- Merchandise Trade Balance: Exports and imports of tangible goods.

- Services Trade Balance: Transactions in sectors such as IT, tourism, banking, and transportation.

- Primary Income: Includes compensation of employees, investment income from foreign assets (dividends, interest).

- Secondary Income: Remittances, grants, gifts, foreign aid, and pensions.

- Capital Account

- Captures capital transfers and acquisitions or disposals of non-produced, non-financial assets (e.g., patents, copyrights).

- Financial Account

- Measures international transactions involving financial assets and liabilities.

- Subcategories:

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): Ownership of at least 10% in a foreign company.

- Portfolio Investment: Short-term financial assets such as stocks, bonds, and derivatives.

- Other Investments: Bank loans, trade credits, and currency deposits.

- Reserve Assets: Central bank reserves in foreign currency, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), gold reserves.

- Current Account

- Double-Entry Bookkeeping in BOP

- Each transaction is recorded as both a credit (inflow) and a debit (outflow), ensuring that BOP always balances.

- Example: If India exports software to the US (credit in current account), the payment received in USD is recorded as a financial outflow (debit in financial account).

- Flows vs. Stocks in BOP Analysis

- Flows: Transactions over a period, impacting BOP positions (e.g., monthly FDI inflows).

- Stocks: Accumulated financial assets or liabilities at a given time (e.g., total foreign exchange reserves at the end of a fiscal year).

Core Concepts of Exchange Rates

- Definition and Types of Exchange Rates

- Nominal Exchange Rate: The rate at which one currency is exchanged for another in the forex market.

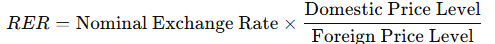

- Real Exchange Rate (RER): Adjusts the nominal exchange rate for differences in price levels across countries. Formula:

- Bilateral Exchange Rate: Rate between two specific currencies (e.g., INR/USD).

- Effective Exchange Rate:

- Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER): A weighted average of a currency’s exchange rates against a basket of currencies.

- Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER): NEER adjusted for inflation differences between domestic and foreign economies.

- Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and Exchange Rate Linkages

- Law of One Price: Identical goods should cost the same in different countries when expressed in the same currency.

- Absolute PPP: Exchange rates should adjust to equalize price levels across nations.

- Relative PPP: Exchange rate changes reflect inflation differentials between countries.

- Example: If India’s inflation is higher than the US, the INR should depreciate relative to USD to restore purchasing power balance.

BOP Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- Concepts of Surpluses and Deficits

- Current Account Surplus: Occurs when exports of goods, services, and income exceed imports.

- Current Account Deficit (CAD): Arises when imports and payments exceed exports and income receipts.

- Capital Account Surplus: Inflows from FDI, portfolio investments, and loans exceed outflows.

- Overall BOP Surplus or Deficit: Determined by summing current, capital, and financial accounts.

- Macroeconomic Implications of BOP Imbalances

- Current Account Deficit Impacts:

- Leads to depreciation of domestic currency due to high demand for foreign exchange.

- Requires financing via capital inflows or foreign exchange reserves.

- Persistent deficits lead to external debt accumulation and currency crises.

- Current Account Surplus Impacts:

- Strengthens currency appreciation, affecting export competitiveness.

- Increases foreign exchange reserves and provides macroeconomic stability.

- India’s Case:

- Historically ran CAD in most years due to high oil imports and trade deficits.

- Managed through FDI inflows, remittances (especially from the Middle East), and RBI forex interventions.

- Current Account Deficit Impacts:

- Policy Targets for BOP Management

- Monetary Policy: Adjusting interest rates to control capital inflows/outflows.

- Fiscal Policy: Modifying government spending and taxation to influence trade balance.

- Exchange Rate Policy: Managing currency levels to maintain competitiveness.

The Role of Capital Mobility

- Short-Run vs. Long-Run Capital Flows

- Short-Run Flows: Speculative investments, portfolio adjustments, exchange rate arbitrage.

- Long-Run Flows: Structural FDI, long-term debt financing, and permanent migration of financial assets.

- Financial Integration and Volatility Considerations

- High Financial Integration:

- Leads to better resource allocation, increased foreign investments, and economic growth.

- Enhances vulnerability to global financial shocks and contagion effects.

- Exchange Rate Volatility:

- Affected by speculative flows, geopolitical tensions, and monetary policy differentials.

- Example: Taper tantrum of 2013 saw massive capital outflows from emerging markets, including India, due to US Federal Reserve’s policy tightening.

- High Financial Integration:

Comparative Overview of Partial-Equilibrium vs. General-Equilibrium Perspectives

| Perspective | Definition | Focus | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial-Equilibrium Analysis | Examines the impact of exchange rate changes on a single market or sector while holding others constant. | Short-run effects on specific industries, trade balances, and capital flows. | Ignores macroeconomic linkages, assumes ceteris paribus (other factors remain unchanged). |

| General-Equilibrium Analysis | Considers interdependencies across multiple markets, sectors, and economic agents. | Long-run macroeconomic adjustments, interconnected effects on GDP, inflation, interest rates, and capital flows. | Requires complex models, relies on assumptions about expectations and rational behavior. |

II – Classical and Keynesian Approaches to BOP Adjustments

Hume’s Price-Specie Flow Mechanism

- Concept and Historical Context

- Developed by David Hume (1711-1776) as a self-correcting mechanism for balance of payments under the Gold Standard (established 1870s, dominant until 1930s).

- Based on the principle that trade imbalances adjust automatically through gold flows and price changes.

- Operated in an era when gold served as the primary monetary standard, meaning a country’s money supply was directly linked to its gold reserves.

- Mechanism of Automatic Adjustment

- Trade Surplus Effect

- A country with a BOP surplus (exports > imports) experiences an inflow of gold from trading partners.

- Increased gold supply expands the domestic money supply, leading to higher price levels (inflation).

- As prices rise, exports become more expensive, reducing international demand.

- Conversely, imports become cheaper, increasing foreign goods’ attractiveness.

- This leads to reduced exports and increased imports, gradually restoring equilibrium.

- Trade Deficit Effect

- A country with a BOP deficit (imports > exports) faces a gold outflow, reducing the domestic money supply.

- Lower money supply causes deflation, decreasing domestic prices.

- Cheaper goods increase exports, while costlier imports decrease, correcting the deficit naturally.

- Trade Surplus Effect

- Limitations in Modern Settings

- No longer applicable in fiat currency systems since most nations abandoned the gold standard after the Bretton Woods collapse in 1971.

- Central banks actively intervene in foreign exchange markets, preventing automatic adjustments.

- Sticky wages and prices delay adjustment, leading to prolonged disequilibrium.

- Financial capital flows distort trade balances, as modern economies rely more on capital flows than gold movements.

Keynesian Income Approach

- Basic Premise

- Introduced by John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) in response to classical theories, emphasizing that income levels drive BOP adjustments rather than price-specie flows.

- Argues that changes in national income, aggregate demand, and employment influence trade balances more than gold flows or price changes.

- Output and Employment Effects

- A country with a BOP surplus sees rising exports, leading to higher national income and employment.

- Increased income raises consumption and imports, reducing the surplus.

- A country with a BOP deficit experiences lower income, reducing demand for imports and improving trade balance.

- This self-regulating mechanism helps achieve external equilibrium.

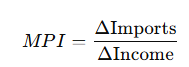

- Marginal Propensity to Import (MPI)

- Measures the proportion of additional income spent on imports.

- Formula:

- A higher MPI means that income growth leads to greater import spending, reducing net exports.

- Example: India’s growing middle class has increased demand for imported electronics and automobiles.

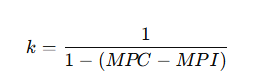

- Multiplier Concept and BOP Adjustments

- Keynesian Multiplier explains how an initial change in spending leads to a larger change in total income and output.

- Formula:

- MPC (Marginal Propensity to Consume) and MPI determine how income changes affect the trade balance.

- If MPI is high, multiplier effects are weaker, making it harder to reduce trade deficits.

- Governments adjust fiscal policies (e.g., increasing investment) to influence trade balances through demand-side interventions.

Absorption and Elasticity Approaches

- Absorption Approach

- Developed by Sydney Alexander (1952), linking BOP to total national expenditure (absorption) rather than money supply or price levels.

- States that BOP balance depends on the difference between national income (Y) and total domestic expenditure (A).

- Equation:

BOP = Y – A - Surplus occurs when Y > A, while deficit occurs when Y < A.

- To correct a deficit, a country must reduce absorption (cut government spending or increase savings).

- Elasticity Approach

- Examines how exchange rate changes affect trade balances through price elasticities of demand for exports and imports.

- Marshall-Lerner Condition

- States that currency depreciation improves trade balance only if the sum of export and import elasticities exceeds 1.

- If demand is inelastic, devaluation fails to correct BOP deficits.

- J-Curve Phenomenon

- Following a currency depreciation, trade balance initially worsens before improving as price adjustments take time.

- Example: Rupee depreciation increases import costs in the short run before making exports competitive.

Comparison Among Classical, Keynesian, and Absorption Theories

| Theory | Key Concept | Policy Implications | Criticisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hume’s Price-Specie Flow | Automatic adjustment via gold flows and price changes | Fixed money supply under gold standard ensures BOP equilibrium | Obsolete under fiat currencies, capital flows dominate trade imbalances |

| Keynesian Income Approach | Income changes drive trade balance adjustments | Fiscal stimulus and employment policies influence imports and exports | Ignores exchange rate effects, assumes automatic employment adjustments |

| Absorption Approach | BOP depends on national income vs. domestic expenditure | Controlling spending can correct BOP deficits | Lacks a direct exchange rate mechanism, ignores capital flows |

| Elasticity Approach | Exchange rate depreciation corrects trade imbalances based on demand elasticities | Devaluation policies can improve exports if demand is elastic | J-Curve effect delays adjustment, ineffective if demand is inelastic |

III – Capital mobility in historical perspective

Evolution of international monetary systems

- Gold standard (1870s – 1930s)

- Established in the 1870s as a system where national currencies were directly tied to gold.

- Countries maintained fixed exchange rates by ensuring currency convertibility into gold at a predetermined rate.

- Encouraged price stability and low inflation due to strict money supply regulation linked to gold reserves.

- Advantages

- Ensured automatic balance of payments adjustment through the price-specie flow mechanism developed by David Hume (1711-1776).

- Promoted global trade stability by reducing exchange rate fluctuations.

- Prevented governments from arbitrarily inflating money supply.

- Limitations

- Required countries to hold large gold reserves, limiting monetary policy flexibility.

- Caused deflationary pressures as money supply was restricted to gold availability.

- Failed to adjust for economic shocks, such as the Great Depression (1929-1939) when deflationary policies worsened global economic conditions.

- Abandonment

- Many countries suspended gold convertibility during World War I (1914-1918) to finance war expenditures.

- The system collapsed after the Great Depression, with Britain abandoning it in 1931 and the United States in 1933 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies.

- The final collapse occurred with the introduction of the Bretton Woods system (1944).

- Bretton Woods system (1944 – 1971)

- Established in 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference, New Hampshire, United States, where 44 nations devised a new global monetary framework.

- Introduced a fixed but adjustable exchange rate system, where currencies were pegged to the US dollar, which was convertible into gold at $35 per ounce.

- Led to the creation of key global institutions:

- International Monetary Fund (IMF, founded 1944) to oversee exchange rate stability and provide financial assistance.

- World Bank (IBRD, founded 1944) to finance post-war reconstruction and development projects.

- Advantages

- Provided a stable exchange rate framework, facilitating rapid global trade growth and post-war recovery.

- Allowed for adjustable pegs, enabling countries to realign currencies during economic imbalances.

- Limitations

- Relied excessively on US dollar dominance, making global stability dependent on US monetary policy.

- Triffin dilemma highlighted inherent contradictions—increasing US dollar supply led to inflation and deficits, undermining confidence in the system.

- Persistent US trade deficits and rising inflation in the 1960s weakened the dollar’s credibility.

- Collapse

- The US faced high inflation and dwindling gold reserves by the late 1960s.

- President Richard Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility in 1971, leading to the system’s collapse and the emergence of a floating exchange rate system.

- Post-Bretton Woods system (1971 – present)

- Shifted to a system of floating exchange rates, allowing currencies to fluctuate based on market demand and supply.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) guidelines allowed managed exchange rate policies, enabling central banks to intervene when necessary.

- Financial markets expanded significantly, leading to greater capital mobility and foreign exchange volatility.

- Key developments

- The rise of currency speculation and hedging strategies due to floating rates.

- Growth of regional monetary agreements, such as the European Monetary System (EMS, 1979) and later the Eurozone (1999).

- Expansion of international financial institutions, including the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, founded 1930).

Phases of financial globalization

- Phase 1: Early financial integration (19th century – 1914)

- Dominated by the gold standard, ensuring stable exchange rates and low capital mobility due to gold constraints.

- Industrial revolution increased cross-border investments in railways, shipping, and manufacturing.

- Colonial economies relied on financial flows from European imperial powers for infrastructure development.

- Phase 2: Disruptions and control (1914 – 1945)

- World War I and Great Depression led to severe disruptions in global trade and capital flows.

- Countries imposed capital controls to prevent currency speculation and protect domestic economies.

- The interwar period (1919-1939) saw competitive devaluations and trade protectionism.

- Phase 3: Bretton Woods era (1945 – 1971)

- Financial globalization was limited due to capital controls, as countries prioritized stable exchange rates over free capital movement.

- Global financial institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, regulated international economic policies.

- Phase 4: Financial liberalization (1971 – 2000s)

- Floating exchange rates led to increased capital mobility, encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investments.

- Deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s saw removal of capital controls in many economies, including India’s economic liberalization in 1991.

- Rapid expansion of international banking, hedge funds, and financial derivatives.

- Phase 5: Contemporary financial globalization (2000s – present)

- Marked by high-speed capital flows, digital currency innovations, and algorithmic trading.

- Globalization brought both economic growth and financial instability, seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

- Growing influence of cryptocurrencies and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) in global financial transactions.

Impact of capital controls vs. free capital mobility

- Motivation for capital controls

- To prevent excessive currency volatility and stabilize domestic financial markets.

- Protect developing economies from speculative attacks and hot money inflows.

- Maintain monetary policy independence without external financial pressures.

- Methods of capital control

- Direct controls

- Limits on foreign exchange transactions.

- Restrictions on foreign ownership in key sectors.

- Indirect controls

- Tobin tax on short-term capital inflows.

- Reserve requirements on foreign investments.

- Direct controls

- Effectiveness in different eras

- Gold standard period

- Capital controls were unnecessary due to fixed exchange rates.

- Bretton Woods era

- Strict capital controls maintained currency stability.

- Post-1971 floating exchange rates

- Capital mobility increased, causing financial volatility.

- 1990s – Present

- Countries gradually lifted controls, making economies vulnerable to financial crises.

- Asian financial crisis (1997) and Global financial crisis (2008) highlighted risks of unrestricted capital mobility.

- Gold standard period

Comparative analysis of capital account regimes across time

| Time Period | Capital Mobility | Policy Tools | External Shocks | Lessons Learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard (1870s-1930s) | Low | Fixed exchange rates, gold reserves | Great Depression (1929) | Gold-linked money supply limits economic flexibility |

| Bretton Woods (1944-1971) | Moderate | Adjustable pegs, IMF stabilization | US inflation crisis (1960s) | Dollar dependency weakens system over time |

| Post-Bretton Woods (1971-Present) | High | Floating exchange rates, forex interventions | Oil shocks (1973, 1979), Financial crisis (2008) | Need for regulatory oversight and macroprudential policies |

IV – Exchange rate regimes and their adjustment mechanisms

Fixed exchange rates

- Concept and Mechanism

- A fixed exchange rate system pegs a country’s currency to another currency, a basket of currencies, or a commodity like gold.

- Governments and central banks maintain a constant exchange rate by buying and selling foreign currency reserves.

- This system was prevalent under the gold standard (1870s-1930s) and the Bretton Woods system (1944-1971) before transitioning to more flexible regimes.

- Types of Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

- Currency Board System

- A strict form where the domestic currency is backed 100% by foreign currency reserves.

- Limits central bank’s ability to conduct independent monetary policy, ensuring exchange rate stability.

- Example: The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (founded 1993) pegs the Hong Kong dollar to the US dollar.

- Pegged Exchange Rate

- The currency is pegged at a fixed rate to another major currency but allows limited fluctuations within a narrow band.

- Central banks intervene through open market operations to keep exchange rates within the target range.

- Example: The Indian rupee was pegged to the British pound and later to the US dollar before moving to a managed float in 1993.

- Currency Board System

- Role of Reserves in Fixed Exchange Rates

- A country using a fixed exchange rate must hold large foreign exchange reserves to stabilize its currency.

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI, established 1935) actively manages forex reserves, which stood at over $600 billion in 2023.

- Forex reserves help in defending the rupee against speculative attacks and external shocks.

- Internal vs. External Balance

- Internal Balance

- Ensuring stable inflation, employment, and economic growth.

- Achieved through fiscal and monetary policies, but restricted under a fixed exchange rate regime.

- External Balance

- Maintaining a sustainable balance of payments (BOP) by aligning trade and capital flows.

- Fixed rates often lead to trade imbalances due to rigid currency valuation.

- Internal Balance

Flexible exchange rates

- Concept and Mechanism

- A flexible exchange rate system allows currencies to fluctuate freely based on market demand and supply.

- No government or central bank intervention, making the exchange rate a reflection of real economic conditions.

- Adopted globally after the collapse of Bretton Woods in 1971.

- Determination by Market Forces

- Demand and Supply in Forex Markets

- Demand for a currency increases when foreign investors buy domestic assets or when exports rise.

- Supply of a currency increases when domestic entities buy foreign goods or invest abroad.

- Macroeconomic Factors Affecting Exchange Rates

- Inflation rates: Lower inflation makes a currency more attractive.

- Interest rates: Higher interest rates attract foreign capital, strengthening the currency.

- Trade balance: A trade surplus strengthens the domestic currency, while a deficit weakens it.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI): Higher FDI inflows create demand for the domestic currency.

- Demand and Supply in Forex Markets

- Role of Speculation in Flexible Exchange Rates

- Speculators trade currencies to profit from exchange rate fluctuations.

- Large-scale speculation can cause currency volatility, affecting economic stability.

- Example: The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was exacerbated by speculative attacks on the Thai baht and other regional currencies.

- Macroeconomic Policy Autonomy

- Under flexible exchange rates, governments can use monetary policy independently to control inflation, interest rates, and economic growth.

- Example: The RBI adjusts repo rates to influence money supply and inflation without concerns about exchange rate stability.

Intermediate regimes

- Concept of Intermediate Exchange Rate Regimes

- These regimes combine elements of fixed and flexible systems to balance stability and autonomy.

- Used by countries that want to avoid extreme volatility while maintaining some degree of policy control.

- Types of Intermediate Exchange Rate Systems

- Crawling Pegs

- The exchange rate is adjusted gradually over time to reflect market conditions.

- Helps in avoiding sudden devaluations while ensuring exchange rate flexibility.

- Example: China followed a crawling peg until transitioning to a managed float in 2005.

- Target Zones

- The central bank maintains exchange rates within a predefined band, allowing moderate fluctuations.

- Provides stability while retaining some flexibility for macroeconomic adjustments.

- Example: European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM, 1979) maintained narrow bands before introducing the euro.

- Basket Pegs

- The currency is pegged to a basket of multiple currencies rather than a single currency.

- Reduces dependence on one foreign currency and minimizes exchange rate shocks.

- Example: India’s exchange rate policy incorporates elements of a basket peg to ensure stability against multiple currencies.

- Crawling Pegs

- Pros and Cons of Partial Flexibility

- Advantages

- Reduces exchange rate volatility, promoting trade and investment.

- Allows for gradual adjustments without drastic economic shocks.

- Balances policy autonomy and external stability.

- Disadvantages

- Requires constant central bank intervention, leading to potential resource misallocation.

- May delay necessary currency adjustments, affecting trade competitiveness.

- Advantages

Differentiating fixed, floating, and intermediate regimes

| Feature | Fixed Exchange Rate | Floating Exchange Rate | Intermediate Regimes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange Rate Control | Government-controlled | Market-driven | Partially controlled |

| Central Bank Intervention | Frequent | Minimal | Occasional |

| Flexibility | Low | High | Moderate |

| Macroeconomic Autonomy | Restricted | Full control | Partial control |

| Trade Stability | High | Low | Moderate |

| Vulnerability to Shocks | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Examples | Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia | US, Japan, Eurozone | China (pre-2005), ERM |

V – Mundell-Fleming framework under capital mobility

Core model assumptions

- Basic Premise

- Developed by Robert Mundell and Marcus Fleming in the early 1960s, this framework extends the IS-LM model to an open economy, incorporating capital mobility and exchange rate regimes.

- Explains how monetary and fiscal policies operate differently under varying degrees of capital mobility and exchange rate regimes.

- Small Open Economy Assumption

- Assumes an economy too small to influence global interest rates, meaning it takes the world interest rate as given (exogenous).

- Example: India’s economy in the 1990s before financial liberalization could be classified as a small open economy due to restricted capital flows and limited integration with global financial markets.

- Perfect vs. Imperfect Capital Mobility

- Perfect Capital Mobility

- Capital moves freely across borders, ensuring interest rate parity.

- Domestic interest rates align with global interest rates due to arbitrage.

- Example: Advanced economies like the US and Eurozone have high capital mobility, allowing investors to shift funds instantly.

- Imperfect Capital Mobility

- Capital flows face restrictions, leading to interest rate differentials across countries.

- Barriers include foreign exchange controls, investment restrictions, and transaction costs.

- Example: India before the 1991 economic liberalization had strict capital controls, making its financial markets less integrated with the global economy.

- Perfect Capital Mobility

- Interest Parity Condition

- Describes how interest rate differences between two countries determine capital flows and exchange rate movements.

- Covered Interest Parity (CIP)

- No arbitrage exists when the domestic interest rate is equal to the foreign interest rate adjusted for forward exchange rate differences.

- Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP)

- Investors expect future exchange rate depreciation/appreciation to balance interest rate differentials.

- Example: A foreign investor deciding between Indian and US bonds considers the interest rate spread and future exchange rate expectations before investing.

Monetary policy transmission

- Effects on Output and Interest Rates

- Expansionary monetary policy (lower interest rates) increases investment and aggregate demand (AD), boosting output.

- Contractionary monetary policy (higher interest rates) reduces inflation but slows economic growth by reducing consumption and investment.

- Effects under Different Capital Mobility Scenarios

- Under Perfect Capital Mobility

- A monetary expansion reduces domestic interest rates, leading to capital outflows and currency depreciation.

- Depreciation improves net exports, increasing GDP, making monetary policy highly effective under flexible exchange rates.

- Under Imperfect Capital Mobility

- Capital outflows are limited, so monetary policy retains some effect on interest rates and domestic demand.

- Example: India’s monetary policy decisions impact domestic borrowing costs but are less affected by global capital flows due to partial capital mobility.

- Under Perfect Capital Mobility

- Effects on Exchange Rates

- Flexible Exchange Rate Regime

- Monetary expansion depreciates the currency, increasing exports and economic output.

- Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

- Central banks intervene to stabilize the exchange rate, limiting the effectiveness of monetary policy.

- Example: China maintained a fixed exchange rate for years, using foreign exchange reserves to prevent currency fluctuations.

- Flexible Exchange Rate Regime

Fiscal policy transmission

- Crowding-Out Effect

- Fiscal expansion (higher government spending or tax cuts) raises interest rates, discouraging private investment.

- Higher interest rates attract foreign capital inflows, appreciating the domestic currency.

- Example: If India increases public spending on infrastructure, higher demand for funds raises interest rates, leading to currency appreciation and reduced exports.

- Exchange Rate Pressures and Effectiveness

- Under Fixed Exchange Rates

- Government spending increases GDP without affecting interest rates, making fiscal policy highly effective.

- However, persistent fiscal deficits lead to currency crises, as seen in the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

- Under Flexible Exchange Rates

- Fiscal expansion raises interest rates, attracting capital inflows and appreciating the currency.

- Currency appreciation reduces net exports, offsetting some of the GDP gains.

- Example: US fiscal stimulus often strengthens the dollar, reducing competitiveness of exports.

- Under Fixed Exchange Rates

- Effectiveness under High Capital Mobility

- When capital moves freely across borders, fiscal expansion leads to large capital inflows and currency appreciation, reducing net exports.

- Example: India’s experience after economic reforms in 1991 showed that fiscal deficits led to external imbalances due to increasing capital inflows.

Extension to large economies and policy coordination

- Spillover Effects

- Policies in one country affect other economies through trade, capital flows, and exchange rate movements.

- Example: US Federal Reserve interest rate changes impact capital flows to emerging markets like India.

- Beggar-Thy-Neighbor Dynamics

- Countries deliberately manipulate exchange rates to boost exports at the expense of trading partners.

- Competitive devaluations lead to currency wars, harming global trade.

- Example: China faced accusations of currency manipulation to maintain an undervalued yuan for export competitiveness.

- Role of Exchange Rate Expectations

- Investors and businesses adjust behavior based on expected currency movements.

- Forward-looking policies reduce uncertainty and improve financial stability.

- Example: India’s RBI manages exchange rate expectations through clear monetary policy communication.

Comparative examination of Mundell-Fleming outcomes

| Factor | High Capital Mobility | Low Capital Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Monetary Policy Effectiveness | Strong under flexible exchange rates | Weak due to capital flow restrictions |

| Fiscal Policy Effectiveness | Strong under fixed exchange rates | Moderate, but crowding-out persists |

| Exchange Rate Regime Impact | Floating enhances monetary policy | Fixed enhances fiscal policy |

| Capital Flow Reactions | Rapid shifts affect stability | Gradual impact on domestic economy |

| Policy Coordination Need | High due to spillovers | Lower risk of external imbalances |

VI – Monetary and fiscal policy interaction in an open economy

Role of central banks under open capital accounts

- Function of Central Banks in Open Economies

- Central banks regulate money supply, control inflation, and stabilize exchange rates in economies with open capital accounts.

- They manage capital inflows and outflows to prevent excessive volatility in currency and interest rates.

- Example: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI, established 1935) plays a crucial role in monetary stability, forex management, and inflation control in India’s liberalized financial environment.

- Interest Rate Rules and Monetary Policy

- Central banks adjust interest rates to influence investment, consumption, and currency values.

- Taylor Rule Model: Guides central banks in setting optimal interest rates based on inflation and output gap.

- Higher interest rates attract foreign capital, strengthening the domestic currency, while lower interest rates boost domestic investment but may cause capital flight.

- Example: RBI adjusts repo rates to manage liquidity, credit availability, and exchange rate stability.

- Inflation Targeting and Exchange Rate Pass-Through

- Many economies follow inflation targeting frameworks, ensuring stable price levels and predictable monetary policies.

- India adopted flexible inflation targeting (FIT) in 2016, with a target inflation rate of 4% ±2%.

- Exchange Rate Pass-Through (ERPT): Measures how exchange rate fluctuations impact domestic inflation.

- A depreciating currency raises import costs, increasing inflation, while an appreciating currency reduces imported inflation.

- Example: India’s rising oil import bills due to rupee depreciation significantly impact inflation levels.

Coordination of fiscal and monetary policy

- Impact on Balance of Payments (BOP)

- Fiscal expansion (higher government spending or tax cuts) increases domestic demand, leading to higher imports and a worsening current account deficit.

- Monetary contraction (higher interest rates) can counteract fiscal expansion by attracting foreign capital and stabilizing the BOP.

- Example: India’s fiscal deficits in the late 2000s led to currency pressures, requiring RBI intervention to stabilize forex reserves.

- Impact on Interest Rates

- Monetary policy influences borrowing costs, while fiscal policy affects public debt and investment demand.

- When monetary tightening (higher interest rates) follows fiscal expansion (higher spending), borrowing costs rise, reducing private investment (crowding out).

- Example: High Indian government borrowing in 2013 led to rising bond yields and reduced private credit availability.

- Impact on Currency Values

- Expansionary fiscal policy raises interest rates, attracting foreign capital and appreciating the currency.

- If monetary policy remains loose (lower interest rates), it leads to capital outflows, weakening the currency.

- Example: Brazil’s currency appreciation in the 2010s was driven by large fiscal stimulus and capital inflows.

Fiscal deficits and debt sustainability

- Ricardian Equivalence Debate

- Ricardian Equivalence Theory (proposed by David Ricardo, 19th century, formalized by Robert Barro in 1974) argues that government deficits do not impact total demand, as rational individuals increase savings to offset future tax burdens.

- Criticism: Assumes perfect foresight and rational behavior, ignoring liquidity constraints and policy credibility issues.

- Example: India’s high fiscal deficit in the early 1990s led to external borrowing and currency depreciation, contradicting Ricardian Equivalence predictions.

- Crowding-In vs. Crowding-Out Effects

- Crowding-Out Effect: High government borrowing increases interest rates, reducing private investment and economic growth.

- Crowding-In Effect: Fiscal expansion in underutilized economies boosts demand, attracting private investment.

- Example: India’s infrastructure spending in 2004-2009 increased private investment, supporting economic growth (crowding-in).

- Global Investor Sentiment and Fiscal Discipline

- Investors monitor fiscal deficits to assess a country’s creditworthiness and risk of capital flight.

- Large deficits may lead to credit rating downgrades, increasing borrowing costs.

- Example: India’s fiscal consolidation post-2013 improved investor confidence, leading to stable capital inflows.

Contrasting monetarist vs. Keynesian perspectives on policy effectiveness

| Factor | Monetarist Perspective | Keynesian Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Policy Focus | Money supply control | Aggregate demand management |

| Monetary Policy Role | Primary tool for stabilization | Effective only in liquidity shortages |

| Fiscal Policy Role | Limited effectiveness | Essential for economic stability |

| Short-Run vs Long-Run | Emphasizes long-run neutrality | Short-run fiscal stimulus matters |

| Inflation Control | Focuses on money supply | Demand-side policies needed |

| Example | 1980s US Fed tightening | Great Depression fiscal spending |

VII – Sterilized vs. non-sterilized intervention and capital flows

Rationales for exchange market intervention

- Purpose of Exchange Market Intervention

- Central banks intervene in foreign exchange markets to stabilize currency values, control inflation, and maintain financial stability.

- Intervention becomes essential when exchange rate volatility disrupts trade, capital flows, and macroeconomic stability.

- Example: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) actively manages rupee fluctuations to prevent excessive appreciation or depreciation.

- Smoothing Volatility

- Excessive currency fluctuations can destabilize exports, imports, and investor confidence.

- Sudden appreciation makes exports expensive, reducing global competitiveness.

- Sharp depreciation increases import costs, especially for essential goods like crude oil.

- Example: RBI intervened during the 2013 rupee crisis to curb excessive volatility and stabilize investor confidence.

- Addressing Misalignments

- Market-determined exchange rates may not always reflect fundamentals, leading to undervalued or overvalued currencies.

- Overvalued currencies hurt exports, leading to trade deficits, while undervalued currencies fuel inflation by making imports expensive.

- Example: China’s managed exchange rate policy keeps the yuan undervalued to boost exports.

- Controlling Inflation

- Exchange rate fluctuations impact inflation through import prices.

- A weaker domestic currency raises inflation, making essential goods expensive.

- A stronger currency reduces inflation by making imports cheaper but hurts export competitiveness.

- Example: RBI’s forex interventions in 2022 aimed to stabilize rupee depreciation and limit inflationary pressures from rising oil prices.

Sterilized intervention mechanisms

- Definition and Mechanism

- Sterilized intervention involves offsetting forex market interventions to prevent changes in money supply.

- The central bank buys or sells foreign currency and neutralizes monetary effects using domestic bond transactions or liquidity adjustments.

- Domestic Bond Transactions

- Buying foreign currency increases money supply, which can fuel inflation.

- To offset this, the central bank sells government bonds, absorbing excess liquidity.

- Selling foreign currency reduces money supply, but the central bank buys government bonds to restore liquidity.

- Example: RBI frequently uses open market operations (OMOs) to manage rupee liquidity after forex interventions.

- Managing Liquidity through Reserve Requirements

- Central banks adjust cash reserve ratios (CRR) or statutory liquidity ratios (SLR) to control liquidity after interventions.

- Increasing CRR reduces bank lending, counteracting inflationary effects of forex purchases.

- Example: India adjusted reserve ratios after large forex interventions to prevent excess liquidity.

- Sterilization Effectiveness Controversies

- Perfect sterilization is difficult as financial markets react to policy changes.

- Partial sterilization occurs when interventions fail to fully offset money supply changes.

- Excessive sterilization can increase interest rates, attracting speculative inflows and creating capital volatility.

- Example: Emerging markets struggle with sterilization costs as bond yields rise due to frequent interventions.

Non-sterilized intervention

- Definition and Mechanism

- Non-sterilized intervention allows forex market operations to influence domestic money supply.

- Central banks buy or sell foreign currency without offsetting liquidity changes, directly impacting monetary conditions.

- Direct Expansion or Contraction of Money Supply

- Buying foreign reserves injects liquidity, lowering interest rates and encouraging credit growth.

- Selling foreign reserves contracts liquidity, raising borrowing costs and slowing inflation.

- Example: China’s rapid reserve accumulation in the 2000s led to liquidity expansion and rising inflation.

- Inflationary and Exchange Rate Impacts

- Non-sterilized forex purchases increase inflation, as higher liquidity boosts demand and price levels.

- Non-sterilized forex sales reduce inflation, tightening money supply and slowing economic activity.

- Example: The US Federal Reserve’s interventions during the 1985 Plaza Accord weakened the dollar but increased inflationary risks.

Assessment of intervention effectiveness under different capital mobility scenarios

| Factor | High Capital Mobility | Low Capital Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Sterilized Intervention Effectiveness | Limited due to speculative inflows | More effective with controlled flows |

| Non-Sterilized Intervention Impact | Increases volatility and inflation | Stronger impact on money supply |

| Exchange Rate Stability | Hard to maintain stability | More control over fluctuations |

| Interest Rate Effects | Sterilization may raise rates | Less impact on interest rates |

| Empirical Evidence | Emerging markets struggle to sterilize effectively | Fixed regimes benefit from direct interventions |

VIII – Currency crises and speculative attacks

Theoretical foundations of currency crises

- Definition and Impact of Currency Crises

- A currency crisis occurs when a nation’s currency experiences a sharp depreciation due to loss of confidence in economic fundamentals.

- These crises lead to capital flight, depletion of foreign exchange reserves, inflation spikes, and economic contractions.

- Example: India faced severe currency pressure during the 1991 balance of payments (BOP) crisis, leading to economic liberalization.

- First-Generation Models (Fiscal Dominance)

- Developed by Paul Krugman in 1979, explaining currency crises due to unsustainable fiscal deficits and excessive money creation.

- Governments finance budget deficits by printing money, leading to inflation and depletion of foreign reserves.

- Investors anticipate eventual devaluation, causing speculative attacks on the currency.

- Example: Latin American debt crises in the 1980s resulted from excessive borrowing, leading to currency crashes.

- Second-Generation Models (Self-Fulfilling Crises)

- Proposed by Maurice Obstfeld in the 1990s, highlighting the role of market expectations in triggering crises.

- Even if fundamentals are sound, investor panic and herd behavior can force a government to abandon a fixed exchange rate.

- A speculative attack drains forex reserves, forcing currency devaluation.

- Example: The 1992 European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) crisis, where George Soros shorted the British pound, leading to its collapse.

- Third-Generation Models (Financial Fragility)

- Developed post-Asian financial crisis (1997), explaining crises due to financial sector weaknesses and excessive foreign-denominated debt.

- Banks and firms borrow heavily in foreign currencies, making them vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations.

- A currency depreciation raises debt burdens, leading to bank failures and deep economic recessions.

- Example: The 1997 Asian financial crisis severely impacted Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea, leading to IMF bailouts.

Role of capital mobility in crisis propagation

- Sudden Stops in Capital Flows

- Currency crises often begin with a sudden halt in foreign capital inflows, leading to liquidity shortages.

- Emerging markets rely on short-term external borrowing, making them vulnerable to global interest rate shocks.

- Example: India faced foreign capital outflows in 2013 due to US Federal Reserve tapering talks, leading to rupee depreciation.

- Contagion Effects

- A crisis in one country spreads rapidly to other economies due to trade linkages and investor panic.

- Investors withdraw funds from multiple emerging markets, fearing similar vulnerabilities.

- Example: The Asian financial crisis spread from Thailand to Indonesia, Malaysia, and South Korea.

- Herd Behavior in International Markets

- Investors follow market trends, exiting currencies based on herd instincts rather than economic fundamentals.

- Speculators coordinate attacks on weak currencies, amplifying financial distress.

- Example: The 1994 Mexican peso crisis (Tequila Crisis) triggered mass capital outflows across Latin America.

Policy responses and crisis resolution

- Capital Controls to Manage Speculation

- Governments impose capital controls to restrict currency speculation and prevent capital flight.

- Controls include restrictions on foreign borrowing, transaction taxes, and mandatory holding periods for foreign investors.

- Example: Malaysia imposed capital controls in 1998 to curb financial speculation and stabilize its currency.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) Assistance Programs

- The IMF (established 1944) provides financial aid to crisis-hit countries under strict conditionality.

- Programs focus on exchange rate stabilization, fiscal austerity, and structural reforms.

- Example: IMF bailouts for South Korea and Indonesia in 1997 required budget cuts and financial sector restructuring.

- Debt Restructuring and Crisis Resolution

- Countries negotiate debt restructuring agreements with international creditors to ease repayment burdens.

- Debt relief includes maturity extensions, lower interest rates, or partial debt write-offs.

- Example: Argentina restructured its external debt after defaulting in 2001, securing creditor agreements to avoid financial collapse.

- Lender-of-Last-Resort Facilities

- Central banks provide emergency liquidity to stabilize banking systems during crises.

- Some countries access swap lines with major central banks to ensure forex liquidity.

- Example: The US Federal Reserve offered dollar swap lines to emerging markets in 2008 to prevent liquidity shortages.

Contrasting different crisis episodes

| Crisis | Causes | Key Events | Lessons for Exchange Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin American debt crisis (1980s) | Excessive borrowing, fiscal deficits | Multiple defaults, IMF intervention | Importance of sustainable debt levels |

| Asian financial crisis (1997) | High foreign debt, capital flight | Currency collapses, IMF bailouts | Need for forex reserves, capital controls |

| European monetary crises (1992, 2010s) | Speculative attacks, financial fragility | UK exits ERM, Greece debt crisis | Managing investor confidence, fiscal discipline |

IX – Policy coordination, global institutions, and the BOP

Rationale for policy coordination

- Need for Coordinated Economic Policies

- Global financial integration has increased economic interdependence, making policy coordination essential for exchange rate stability, trade balance adjustments, and capital flow regulation.

- Without coordination, unilateral policies can create external imbalances, trade wars, and financial crises.

- Spillover Effects in the Global Economy

- Economic policies in one country impact others through trade, investment flows, and exchange rate adjustments.

- Example: The US Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes affect capital flows to emerging markets like India, leading to rupee depreciation and forex volatility.

- Expansionary fiscal policies in advanced economies increase import demand, benefiting export-driven economies like China and Germany.

- Prisoner’s Dilemma in Economic Policies

- Countries acting in self-interest often create worse outcomes than coordinated efforts.

- Example: If all nations devalue their currencies simultaneously to boost exports, no country gains a competitive edge, but global instability increases.

- Trade protectionism during financial crises worsens global recessions rather than promoting recovery.

- Race to the Bottom in Exchange Rate Policies

- Some nations engage in competitive currency devaluations to boost exports and reduce trade deficits.

- Example: China’s managed currency depreciation has drawn criticism for distorting trade balances.

- Excessive monetary easing in developed economies leads to capital outflows from emerging markets, increasing financial vulnerabilities.

Role of the IMF and World Bank

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) – Founded 1944

- Objective: Ensure global financial stability through exchange rate surveillance, financial assistance, and policy advice.

- Surveillance Mechanism

- Monitors global economic conditions, currency misalignments, and financial risks.

- Publishes World Economic Outlook (WEO) and Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) to guide policymakers.

- Conditionality in IMF Assistance

- Provides bailouts to countries facing currency crises, requiring structural reforms in return.

- Example: IMF loans to Greece in 2010 came with austerity conditions, reducing fiscal deficits but deepening recession.

- Criticism of the IMF

- Imposes one-size-fits-all policies, often worsening economic downturns.

- Encourages excessive fiscal austerity, slowing post-crisis recoveries.

- Dominated by developed economies, limiting influence of emerging markets like India.

- World Bank – Founded 1944

- Objective: Provide long-term development financing for infrastructure, poverty reduction, and institutional reforms.

- Financial Assistance Mechanisms

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) offers loans to middle-income countries.

- International Development Association (IDA) provides concessional financing to low-income countries.

- Criticism of the World Bank

- Lending conditionalities often favor donor country interests, reducing effectiveness.

- Funds large infrastructure projects that sometimes displace local communities and harm the environment.

- Example: Dam projects funded in India have faced opposition due to ecological concerns.

G20 and other forums

- G20 – Founded 1999

- Objective: Facilitate global economic cooperation among major economies, ensuring financial stability and inclusive growth.

- Role in Policy Coordination

- Monitors global macroeconomic trends, coordinating responses to crises.

- Encourages structural reforms for sustainable growth.

- Example: G20 nations implemented coordinated stimulus measures in response to the 2008 global financial crisis, preventing a deeper recession.

- Multilateral vs. Bilateral Coordination

- Multilateral Coordination

- Involves multiple countries working together through global forums.

- Ensures balanced decision-making and shared responsibility.

- Example: World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations aim for multilateral trade agreements.

- Bilateral Coordination

- Involves two countries negotiating economic agreements directly.

- Faster decision-making but may lead to trade imbalances favoring stronger economies.

- Example: India-US trade agreements involve bilateral negotiations on tariff adjustments and market access.

- Multilateral Coordination

- Currency Diplomacy and Regulatory Harmonization

- Central banks coordinate monetary policies to prevent currency wars.

- Regulatory standards align financial market policies, reducing risks of speculative crises.

- Example: The Basel III banking regulations promote capital adequacy standards globally.

Distinguishing unilateral vs. multilateral approaches

| Approach | Definition | Success Rate | Burden Distribution | Strategic Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral | Individual country acts alone | Low due to global dependencies | Concentrated on single country | Competitive devaluations, protectionism risks |

| Multilateral | Coordinated policy-making | Higher due to cooperation benefits | Shared across multiple nations | Reduces trade conflicts, stabilizes economies |

X – Empirical evidence and methodological advances

Econometric approaches to studying exchange rate adjustments

- Use of Econometric Models in Exchange Rate Analysis

- Empirical studies use quantitative models to analyze exchange rate fluctuations, policy effects, and financial stability.

- Key econometric approaches include Vector Autoregression (VAR) models, cointegration analysis, and structural modeling.

- VAR Models (Vector Autoregression)

- Capture dynamic relationships among macroeconomic variables without imposing structural restrictions.

- Used to assess exchange rate responses to shocks in monetary policy, inflation, and trade balance.

- Example: A VAR model can measure how RBI’s repo rate changes impact rupee exchange rates and capital inflows.

- Cointegration Analysis

- Examines long-term equilibrium relationships between exchange rates, inflation, and interest rates.

- Helps determine whether exchange rate movements are driven by fundamental economic variables or speculative pressures.

- Example: Empirical studies on India’s exchange rate policy use cointegration tests to evaluate the impact of foreign capital inflows on the rupee’s value.

- Structural Modeling

- Specifies causal relationships among variables based on economic theory.

- Includes structural VAR (SVAR) models and Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models to predict policy outcomes.

- Example: A DSGE model assesses the long-run effects of capital account liberalization on exchange rate stability in emerging markets.

Impact of capital mobility on policy effectiveness

- Empirical Findings on Interest Rate Differentials

- High capital mobility reduces monetary policy autonomy as domestic interest rates align with global financial conditions.

- Studies show that interest rate pass-through is stronger in open economies, where central banks have limited ability to control borrowing costs.

- Example: India’s bond yields fluctuate based on US Federal Reserve rate changes, limiting RBI’s monetary independence.

- Inflation Pass-Through in Open Economies

- Exchange rate fluctuations impact domestic price levels through imported inflation.

- High capital mobility increases exchange rate sensitivity, amplifying inflation volatility.

- Example: The 2018 rupee depreciation led to rising fuel and commodity prices, increasing inflationary pressures in India.

- Growth Outcomes and Capital Mobility

- Empirical studies link capital mobility to economic growth, depending on institutional quality and financial market depth.

- Developed economies benefit from financial openness, while emerging markets face volatility and crisis risks.

- Example: Post-1991 economic reforms in India increased FDI inflows, boosting growth but also raising external vulnerabilities.

Dynamic panel studies of exchange rate regimes

- Long-Run Performance of Exchange Rate Regimes

- Panel studies compare fixed, floating, and intermediate exchange rate regimes across multiple countries.

- Findings suggest floating regimes enhance monetary policy autonomy, but fixed regimes provide exchange rate stability.

- Example: Asian economies with managed exchange rates experience lower volatility but require large forex reserves.

- Crisis Resilience Under Different Regimes

- Fixed exchange rate regimes suffer from speculative attacks when forex reserves are insufficient.

- Floating regimes adjust faster but increase short-term volatility.

- Example: Argentina’s currency peg collapsed in 2001 due to insufficient reserves, triggering a financial crisis.

- Exchange Rate Misalignment Issues

- Studies evaluate whether exchange rates deviate from fundamental values, leading to trade imbalances.

- Misalignment can cause persistent trade deficits or surpluses, affecting global economic stability.

- Example: China’s undervalued yuan led to prolonged US trade deficits, fueling trade tensions.

Comparative analysis of empirical methods

| Empirical Method | Definition | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectional Analysis | Compares multiple countries at a single point in time | Identifies broad trends | Ignores time dynamics, cannot capture crises |

| Time-Series Analysis | Examines exchange rate changes over time | Captures historical patterns | Sensitive to structural breaks, requires long data series |

| Micro-Level Data Studies | Focus on firm-level or transaction-level data | Detailed insights on behavior | Limited macroeconomic implications |

| Macro-Level Data Studies | Use national economic indicators | Explain policy effectiveness | May overlook firm-level variations |

XI – Contemporary debates and critiques

Debate on managed floats vs. pure floats

- Concept of Exchange Rate Flexibility

- Managed float refers to a currency regime where the central bank intervenes occasionally to stabilize excessive volatility.

- Pure float allows exchange rates to be entirely determined by market forces without central bank intervention.

- Example: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) follows a managed float system to stabilize rupee fluctuations.

- Effectiveness of Exchange Rate Smoothing

- Managed float helps reduce excessive short-term volatility, preventing sharp swings that could disrupt trade and investment.

- Intervention stabilizes inflationary pressures arising from exchange rate fluctuations.

- Example: During the 2013 rupee crisis, RBI intervened by selling foreign reserves to prevent excessive depreciation.

- However, excessive central bank interventions distort price signals, leading to inefficiencies.

- Transparency and Market Expectations

- A pure float system enhances transparency, as exchange rates reflect real supply and demand forces.

- Managed floats create uncertainty, as markets do not always know the extent of intervention.

- Example: China’s intervention in yuan valuation often leads to unpredictability in global currency markets.

- Controversies Over Market Interventions

- Critics argue that frequent intervention leads to excessive reliance on forex reserves.

- Emerging markets face challenges in defending their currencies against speculative attacks due to limited reserves.

- Example: The 1997 Asian financial crisis showed the risks of excessive intervention when Thailand’s central bank exhausted its forex reserves defending the baht.

Currency manipulation accusations

- Concept of Currency Manipulation

- A country artificially undervalues its currency to gain a trade advantage by making exports cheaper and imports more expensive.

- Example: The US frequently accuses China of keeping the yuan undervalued to maintain a trade surplus.

- Trade Imbalances and Competitive Devaluations

- Undervalued currencies lead to persistent trade imbalances, favoring exporting nations.

- Competitive devaluations create a “beggar-thy-neighbor” effect, where countries engage in currency wars.

- Example: Japan’s yen devaluation in the 1980s and China’s yuan devaluation in the 2000s led to global trade tensions.

- Moral Hazard Concerns in Currency Policy

- Nations engaging in artificial devaluation may become over-reliant on external demand.

- Excessive currency interventions encourage speculation, increasing financial instability.

- Example: Brazil’s real faced instability in the early 2010s due to persistent currency interventions to protect exports.

Critiques of the Mundell-Fleming model

- Simplifying Assumptions and Real-World Complexity

- The Mundell-Fleming model assumes perfect capital mobility, ignoring practical restrictions on capital flows.

- Fixed vs. floating exchange rate assumptions oversimplify macroeconomic reality.

- Example: India follows a managed float, which is neither purely fixed nor entirely floating.

- Neglect of Financial Frictions

- The model ignores liquidity constraints, banking crises, and financial market imperfections.

- Example: The 2008 global financial crisis highlighted the role of liquidity shortages, which the model does not account for.

- Incomplete Rational Expectations

- Assumes investors and policymakers act with perfect foresight, which does not align with real-world uncertainty.

- Example: Exchange rate expectations in India fluctuate due to geopolitical risks, trade policies, and interest rate movements.

Comparison of mainstream vs. heterodox critiques

| Perspective | Core Focus | Key Criticism | Policy Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream Economic Theory | Market efficiency, rational expectations | Assumes perfect information, ignores crises | Supports free capital mobility |

| Post-Keynesian View | Demand-driven instability | Exchange rates are volatile, require regulation | Advocates capital controls |

| Structuralist View | Developing economies’ vulnerabilities | Floating rates harm weaker economies | Supports managed exchange rates |

| Neo-Marxist View | Global financial power imbalance | Exchange rates favor developed economies | Calls for alternative financial systems |

XII – Future perspectives on exchange rate adjustments under capital mobility

Emergence of digital currencies and fintech

- Transformation of Exchange Rate Mechanics

- Digital currencies and financial technology (fintech) innovations are reshaping how currencies are traded, valued, and managed.

- Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) challenge traditional foreign exchange markets.

- Blockchain-based transactions reduce dependence on intermediary banks, altering forex market dynamics.

- Example: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced the digital rupee in 2022, signaling a shift toward digital payments and currency management.

- Potential Disruption to Capital Flow Management

- Cryptocurrency transactions bypass capital controls, complicating central bank interventions.

- Fintech firms enable real-time cross-border payments, reducing reliance on traditional SWIFT-based systems.

- Example: El Salvador adopted Bitcoin as legal tender in 2021, bypassing conventional forex mechanisms.

- Challenges in Exchange Rate Stability

- Increased adoption of digital assets creates exchange rate volatility due to speculative trading and lack of regulatory oversight.

- CBDCs offer more stability but may require coordination among central banks to avoid fragmented currency markets.

- Example: China’s digital yuan trials indicate a shift toward government-backed digital currencies over decentralized cryptocurrencies.

Global macroprudential policies

- Targeting Systemic Risk in Capital Mobility

- Macroprudential policies aim to prevent financial crises by regulating capital inflows, credit growth, and banking sector risks.

- Flexible exchange rates alone cannot prevent financial instability, requiring coordinated macroprudential measures.

- Example: India imposed capital inflow restrictions in 2013 to curb excess volatility during the US Federal Reserve’s tapering crisis.

- Cross-Border Spillovers and Exchange Rate Adjustments

- Uncoordinated monetary policies create spillover effects across countries, influencing capital movements and exchange rate stability.

- Example: US interest rate hikes lead to currency depreciation in emerging markets like India, triggering capital outflows.

- Coordinated capital flow management prevents excessive volatility in currency markets.

- New Forms of Capital Control in the Digital Age

- Traditional capital controls regulate foreign exchange reserves, investment flows, and external borrowings.

- Digital capital controls may include taxation on crypto transactions, tracking decentralized finance (DeFi) networks, and regulating fintech-based remittances.

- Example: China restricted crypto exchanges in 2021 to maintain control over capital flows and financial stability.

Sustainable external adjustment in the green economy

- Environmental Factors in Exchange Rate Policies

- Climate policies influence international trade competitiveness, affecting currency valuations.

- Green technology adoption increases capital inflows for countries investing in sustainable industries.

- Example: India’s push for solar energy has attracted foreign investments, influencing capital account dynamics.

- Carbon Border Taxes and Exchange Rate Effects

- Carbon border taxes adjust import prices based on carbon footprints, impacting global trade balances.

- Countries with higher carbon emissions may face depreciating exchange rates due to reduced trade competitiveness.

- Example: The European Union’s proposed carbon border tax could affect India’s steel and textile exports.

- Shifts in Comparative Advantage and Currency Valuations

- Nations investing in renewable energy and green infrastructure strengthen their long-term exchange rate stability.

- Fossil-fuel-dependent economies face capital outflows as investors shift toward sustainable industries.

- Example: Norway’s currency remains strong due to its sovereign wealth fund investments in green technology.

Contrasting potential trajectories of the international monetary system

| Potential Trajectory | Key Characteristics | Implications for Exchange Rates | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multipolar Currency World | Multiple reserve currencies replace US dollar dominance | Exchange rate volatility decreases as power is distributed | Coordination among central banks needed |

| Continued Dollar Dominance | US dollar remains primary global reserve currency | Stable trade relationships, predictable forex markets | Overreliance on US monetary policy |

| Regional Blocs | Regional currency unions like the Eurozone expand | Currency stability within regions, reduced forex risk | Loss of national monetary sovereignty |

- Examine how capital mobility affects the effectiveness of monetary policy and evaluate the role of exchange rate regimes in balancing internal and external objectives. (250 words)

- Discuss the primary arguments of classical and Keynesian theories of balance of payments adjustments, highlighting their implications for currency stability under high capital mobility. (250 words)

- Critically analyze how exchange rate interventions interact with fiscal and monetary policies in preventing currency crises, and assess whether these strategies are sustainable under globalization. (250 words)

Responses