Why Southern Indian States Fear Delimitation: Political & Economic Implications

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

IAS EXPRESS Vs UPSC Prelims 2024: 80+ questions reflected

Delimitation is the process of redrawing the boundaries of electoral constituencies to reflect changes in population. In India, this exercise determines the boundaries and number of Lok Sabha (Parliament) and State Assembly constituencies, ensuring each elected representative speaks for roughly an equal number of people. Delimitation is significant because it upholds the democratic principle of “one person, one vote, one value.” By periodically adjusting constituencies, the representation remains fair – areas with population growth gain more representatives, preventing some regions from becoming under-represented or over-represented. In essence, delimitation maintains balanced representation in Parliament and state legislatures as the population changes. However, the prospect of a new delimitation exercise has caused apprehension in India’s southern states, who fear it may reduce their political voice despite their progress in controlling population growth.

Historical Context

Delimitation in India has evolved through the decades. After independence, the Constitution of India mandated that constituencies be redrawn after every decennial census to account for population shifts. Delimitation exercises were carried out in 1952, 1963, and 1973, following the 1951, 1961, and 1971 censuses respectively. Each time, the number of Lok Sabha seats was increased in proportion to population growth – for example, the Lok Sabha expanded from 494 seats (in the 1950s) to 522 and then to the current 543 seats by 1973. However, in 1976, during the Emergency era, the government instituted a moratorium on further delimitation. This freeze, introduced via the 42nd Constitutional Amendment, meant that the number of Lok Sabha and Assembly seats allocated to each state would remain fixed based on the 1971 census, despite future population changes. The freeze was originally meant to last until 2001, as an incentive for states to implement family planning and stabilize population growth. In 2001, the 84th Amendment extended this freeze until the first census after 2026. As a result, while internal constituency boundaries were adjusted in 2002 (after the 2001 census) to even out population among constituencies within each state, the allocation of seats to each state has remained the same since 1971. This historical decision to freeze representation is at the root of today’s regional anxieties about delimitation.

Constitutional Provisions

Several constitutional provisions and laws govern delimitation in India. Article 82 of the Constitution requires Parliament to enact a Delimitation Act after every census, enabling the re-adjustment of Lok Sabha seats among states as per the latest population figures. Similarly, Article 170 requires States to undergo periodic delimitation for their legislative assembly constituencies. These provisions reflect the principle that representation should track population changes. Parliament has passed Delimitation Commission Acts from time to time (1952, 1962, 1972, and 2002) to constitute independent Delimitation Commissions. Each Commission, headed by a retired Supreme Court judge, is tasked with redrawing constituency boundaries and allocating seats to states in a fair manner. Importantly, amendments to the Constitution have modified these provisions: the 42nd Amendment (1976) added a proviso to Article 82 and Article 170 postponing delimitation, and the 84th Amendment (2001) further extended this suspension up to 2026. Therefore, until 2026, the number of seats in the Lok Sabha for each state cannot be changed. The Constitution thus both empowers delimitation as a tool for equal representation and, through amendments, has allowed temporary freezes to serve other policy goals like population control. With the freeze expiring soon, the constitutional mandate for fresh delimitation will resume, bringing these provisions back into active play.

Political Implications of Delimitation

Delimitation has major political implications because it directly affects representation in legislatures. In a democracy, political power is tied to the number of elected representatives a region sends to Parliament. If constituencies are redrawn strictly according to updated population, areas that have grown more populous will gain more seats, enhancing their influence in law-making and government formation. Conversely, regions with relatively stable or declining population shares may gain fewer new seats or even lose some share of representation if the total number of seats is fixed. This reshaping of representation can alter the balance of power between states and regions.

At the national level, delimitation impacts how much say a state has in the Lok Sabha. More MPs from a state mean greater clout in coalition-building, policymaking, and budget allocations. It can influence which states dominate political discourse and leadership. The principle of equal representation (each MP representing a similar population size) is crucial for fairness, but it can conflict with political realities. For decades, the freeze on delimitation preserved the status quo of state-wise seats, preventing any region from losing seats. Once this freeze is lifted, we could see a significant shift: states that have experienced higher population growth (largely in the Hindi-speaking north) would justifiably demand more seats to honor the one person, one vote principle. Politically, this means power could tilt further towards those populous northern states, potentially diminishing the relative voice of others, notably the south. This prospect has made southern Indian states nervous, as they anticipate a reduction in their representation ratio and hence a weaker position in national politics. In short, delimitation is not just a technical exercise – it is a politically charged process that can redefine how power is distributed in India’s federal structure.

Economic and Social Implications

Beyond pure politics, delimitation carries economic and social implications. Government representation is linked to resource allocation and development priorities. Regions with greater representation can more effectively lobby for central projects, infrastructure, and welfare schemes. If southern states end up with proportionally fewer MPs, they worry that their ability to influence the distribution of central funds and investments might shrink. This is significant because many southern states are economic powerhouses – they have higher per-capita incomes and contribute substantially to India’s tax revenues and GDP. A decline in representation could potentially lead to fiscal imbalances, where regions contributing more might feel they are getting less attention or returns in national decision-making.

Socially, the delimitation outcome could affect how different communities are represented. For instance, constituencies in northern states are currently very large in population, which strains governance and local outreach. Delimitation would reduce the population per constituency in those areas, likely improving the quality of representation and access to MPs for citizens there. On the other hand, citizens in southern states currently enjoy relatively smaller constituency sizes and closer interaction with their representatives; if their number of constituencies does not increase in line with population elsewhere, their MPs will form a smaller bloc nationally. There’s also an important societal angle: southern states have generally led in human development indicators (health, education, family planning). The fear is that if political attention shifts overwhelmingly to issues in the more populous north, policies catering to the advanced developmental needs of the south (such as higher education, technology, urban infrastructure) might receive less priority. In summary, who gets how many seats is not just a numbers game – it can influence how resources are shared and which social issues receive focus across India’s regions.

Comparison with Northern States and Their Gains

Northern states, especially the Hindi heartland (like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan), are poised to benefit significantly from delimitation post-2026. These states have seen faster population growth over the last few decades compared to the national average. Under the frozen arrangement based on the 1971 census, many northern states are under-represented relative to their current populations. For example, Uttar Pradesh (UP), India’s most populous state, still has 80 Lok Sabha seats – a number set when its population was much smaller. If seats are reallocated by today’s population, UP stands to gain a large number of additional seats. Some projections suggest UP could have around 120 MPs or more in an expanded Lok Sabha, reflecting its huge population. Similarly, Bihar, with 40 seats at present, could see its tally rise towards 60 or 70. Other northern and central states like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Jharkhand would also gain new constituencies to match their population numbers.

By contrast, the southern states have had slower population growth due to successful family planning and development. States like Tamil Nadu (currently 39 seats) or Kerala (20 seats) might see only a minimal increase in seats, or possibly none at all if the total number of Lok Sabha seats isn’t increased significantly. In a scenario where the Lok Sabha is enlarged to accommodate population-based representation (for instance, increasing the total seats from 543 to around 750+), every state will gain some seats, but not uniformly. The share of northern states in Parliament would rise substantially. The combined representation of the five southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala) is about 24% of Lok Sabha seats today. This percentage could drop to around 19-20% after delimitation, because the total number of seats from populous northern states would grow at a faster rate. In essence, northern states view delimitation as a long-awaited correction that will give their citizens equal voice commensurate with their numbers. From their perspective, it is about democratic fairness – each MP should represent roughly the same number of people across India. The divergent demographic trends have created this scenario where the north gains and the south potentially loses out. This North-South difference in outcomes is at the heart of why their perspectives on delimitation differ so greatly.

Why Southern States Are Concerned

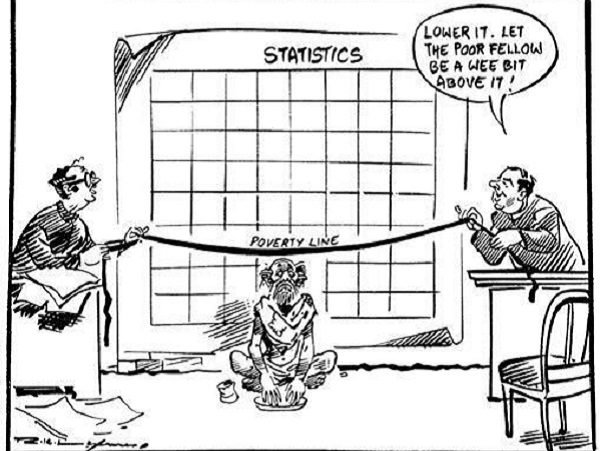

Southern Indian states are nervous about delimitation for several interrelated reasons. First and foremost is the issue of population growth differences. Southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Karnataka have spent the past decades actively promoting family planning, education, and women’s empowerment, resulting in lower birth rates. Many of them now have fertility rates at or below the replacement level, and their population growth has stabilized. In contrast, several northern states continued to have higher fertility rates until more recently, leading to a population boom. Because the upcoming delimitation would redistribute political representation based on population, southern leaders feel they are being penalized for success. They followed national calls to control population growth, only to find that doing so might reduce their representation in Parliament relative to states that did not control population as effectively.

Another concern is the potential loss of political influence. Southern states worry that a reduction in their share of Lok Sabha seats will make it harder for them to protect their interests at the national level. Fewer MPs from the south could mean less weight in parliamentary votes, fewer cabinet positions for their representatives, and less say in choosing the Prime Minister or shaping national policies. This is especially troubling for southern states given their strong track record in economic development and social progress. They fear a Parliament dominated by MPs from the north might prioritize issues of the populous northern belt, possibly overlooking the unique needs or contributions of the south. There is also an economic dimension to their anxiety: Southern states contribute a significant portion of India’s revenues and exports. Leaders from the south argue that political representation should also take into account factors like a state’s contribution to the national economy or success in governance, not just raw population. Some have gone so far as to label the delimitation outcome a form of imbalance or injustice, wherein states that advanced through good governance might have a weaker voice in the federal setup. In public statements, southern chief ministers and parties have warned against any delimitation formula that “rewards population growth and punishes development.” They seek assurances that they will not outright lose existing seats and that their decades of progress will not result in diminished standing in the Union. This combination of pride in their development, fear of reduced influence, and a sense of unfairness drives the strong reservations southern states have about the forthcoming delimitation.

Possible Solutions and Recommendations

Finding a balance between democratic fairness and regional equity is challenging, but several solutions have been proposed to address the southern states’ concerns while carrying out delimitation:

- Increase the Total Number of Seats: One practical solution is to expand the size of the Lok Sabha significantly so that rapidly growing states gain more seats without reducing the absolute number of seats of the slower-growing states. For instance, if the total seats increase from 543 to say 750, states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar would gain many new constituencies, but states like Tamil Nadu or Kerala could retain their current counts or even gain slightly. This way, no state “loses” seats even if their proportion of the total becomes smaller. The Union government has hinted that no southern state will lose any existing seat in this process, suggesting seat expansion is likely.

- Gradual or Phased Delimitation: Another recommendation is to implement changes gradually. Instead of a sudden jump to a new distribution, the delimitation could be phased in over multiple election cycles. This would give states time to adjust to the new reality and soften the immediate political impact. A phased approach could also be paired with interim measures to support states that see a relative decline in representation.

- Alternate Criteria for Representation: Some experts and regional leaders suggest that factors other than population could be given a small weight in allocating seats. Ideas include considering a state’s performance in human development, health, education, or its contribution to GDP and tax revenues. While the primary basis would remain population to uphold equal suffrage, a slight adjustment or bonus for well-performing states could be introduced to reward progress and not discourage states from pursuing development. This would, however, require complex constitutional changes and consensus, as it departs from the pure population-based representation principle.

- Strengthen Federal Institutions: To alleviate fears of marginalization, India can strengthen institutions like the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) or the Inter-State Council. The Rajya Sabha, where states are represented (though currently roughly by population as well), could be reformed to give greater voice to smaller or lower-population states (similar to the U.S. Senate model of equal state representation, though that would be a drastic change for India). Additionally, bodies like the Inter-State Council could be made more active for negotiating between the center and states, ensuring southern states’ concerns are heard in policymaking regardless of Lok Sabha seat counts.

- Continued Incentives for Population Control: The original spirit behind freezing delimitation was to encourage population control. Even as that freeze ends, the central government can continue rewarding states that manage population well – for example, through favorable allocations in central schemes or additional finance commission grants for demographic management. The Finance Commissions in recent years have indeed tried to strike a balance by considering 1971 population for some calculations and giving incentive grants for demographic efforts. Similar creative fiscal and administrative measures can ensure southern states do not feel financially worse-off due to representation changes.

In conclusion, a combination of these approaches may be needed. The goal should be to update representation in line with democratic norms while maintaining national unity and a sense of fairness. Any solution will require building a political consensus at the national level so that all states accept the outcome as just and equitable.

Key Differences and Impacts: Northern vs Southern States (Summary)

To summarize the scenario, the following table and points highlight the key differences between southern and northern states regarding delimitation and its impacts:

| Aspect | Southern States | Northern States |

|---|---|---|

| Population Growth (1971–2021) | Low to Moderate (due to successful family planning) | High (significant increase due to higher birth rates) |

| Fertility Rates & Demographics | Near or below replacement level; aging population trend starting in some areas | Above replacement level until recently; younger population demographic |

| Current Lok Sabha Seats (Frozen allocation) | Relatively more seats per population (benefited from freeze) – e.g. ~1.5–2 million people per MP on average | Relatively fewer seats per population – e.g. ~2.5–3 million people per MP, indicating under-representation currently |

| Expected Change After Delimitation | Small increase in seat numbers, leading to a lower percentage share of total seats (diluted influence) | Large increase in seat numbers, leading to a higher share of total seats (enhanced influence) |

| Political Influence Concern | Fear of losing voice in Parliament and federal decisions; feel “punished” for population control success | Anticipation of greater influence and fair share of representation reflecting population; feel current under-representation will be corrected |

| Economic Consideration | High economic output and tax contribution relative to population, raising demand for commensurate voice in decisions | Development needs are high due to large populations; seek resources and representation to improve infrastructure and services |

- Population Control vs. Representation: Southern India’s slower population growth means these states could see their representation share shrink, whereas northern states with higher growth will gain more seats. This creates a tension between rewarding population control and ensuring equal representation per citizen. Southern leaders worry that they are being “punished for doing the right thing” by controlling population.

- Shift in Parliamentary Power: With delimitation, political power in the Lok Sabha is likely to shift northwards. Heavily populated states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar would command a larger block of MPs, potentially dominating parliamentary votes and national politics. Southern states are concerned about a corresponding decline in their parliamentary clout, from about one-quarter of Lok Sabha seats now to perhaps one-fifth in the future.

- Resource Allocation and Development: More MPs from a region can push for greater infrastructure projects, budget allocations, and welfare schemes for that region. Northern states, which often have greater development needs, stand to benefit from this. However, the South fears that a loss in relative representation may translate to less influence over national resource distribution, even though southern states contribute heavily to the economy.

- Regional Disparities and Unity: The North-South divide in representation might widen regional disparities and could fuel political friction. Southern states emphasize that national unity could be impacted if a large section of the population (South Indians) feels systematically under-represented. There is a call for balance to prevent alienation, ensuring that delimitation does not lead to feelings of domination by any one region.

These points encapsulate why the issue of delimitation is so sensitive: it affects not only electoral maps but also the fabric of federal fairness and unity in India.

Conclusion

Delimitation is a constitutionally mandated exercise vital for keeping India’s democracy representative. As the country prepares to redraw the electoral map after 2026, it faces a delicate balancing act. On one hand lies the principle of equal representation based on population – a cornerstone of democracy that ensures each citizen’s vote has equal weight. On the other hand lie the genuine concerns of southern states that have diligently controlled population growth and fear a diminished voice in the nation’s affairs as a consequence. The nervousness of the southern states about delimitation stems from this clash of principles and interests.

A balanced approach will be necessary to navigate the future. Policymakers must assure southern states that they will not be unfairly marginalized, perhaps by increasing the overall number of seats and innovating with solutions that acknowledge contributions to national development. At the same time, the country cannot indefinitely postpone aligning representation with population, as northern states rightly expect their growing populations to be reflected in Parliament. The coming delimitation, therefore, must be handled with care and consensus. With open dialogue and statesmanship, India can arrive at a formula that upholds democratic equality without eroding the trust and cooperative spirit between its states. In the long run, the goal should be to reduce regional disparities – both in population growth and development – so that future delimitation exercises do not trigger such apprehensions. For now, all eyes are on 2026 and beyond, as India seeks to balance fairness to its citizens with fairness to its states in the great democratic exercise of delimitation.

Practice Question

Critically analyze the impact of delimitation on the political representation of southern Indian states. Discuss its implications on federalism, resource allocation, and regional development. Suggest measures to address emerging concerns. (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.